When considering the largest navies in the world during the twentieth century, some obvious contenders come to mind, like the United States and the Soviet Union, the dominant powers during the half-a-century-long Cold War.

Yet there is one unexpected member of the list of top navies: PepsiCo, the manufacturer of Pepsi Cola.

So why did Pepsi have a navy? How did Pepsi get a navy? What happened to Pepsi’s navy? In 1989, the company traded soda products with the Soviet Union in return for naval vessels: 17 ships in total.

The trade encapsulated the victory of capitalism in the ideological conflict of the Cold War by granting a corporation enough military hardware to be the 6th largest navy in the world.

Drinking Pepsi In The Soviet Kitchen

The connection between Pepsi and the Soviet Union began 30 years before the Pepsi Navy, as the company planted the seeds early in the Cold War.

During the 1950s, the Soviet Union became an economic powerhouse, quickly outpacing the growth of the United States during one of its most economically prosperous decades.

Economic growth alongside scientific advancements that included the Soviets’ rapid development of the atomic bomb and the launch of Sputnik as the first space vessel set the Soviets ahead early on in the global conflict.

This raised alarms within the highest ranks of the American political system, and President Eisenhower took steps to reestablish and maintain the United States’ foothold as the predominant world power.

In 1959, Eisenhower organized the National Exhibition in Moscow, a showcase that exemplified the benefits and allure of American products and lifestyles.

American brands such as General Electric, Kodak, and Pepsi displayed their products at the exhibition, while the highlight of the event was what became known as the “Kitchen Debate.”

Vice-president Richard Nixon debated Soviet Chairman Nikita Khrushchev over the benefits of capitalism vs. communism, an attempt from both sides to promote their respective systems.

While the United States did not rocket ahead of the Soviet Union as a result of the exhibition, there was one person who benefitted immensely as a result: Donald Kendell, a Pepsi executive who had backed Pepsi’s involvement with the exhibition in the face of intense criticism from his superiors within the corporation.

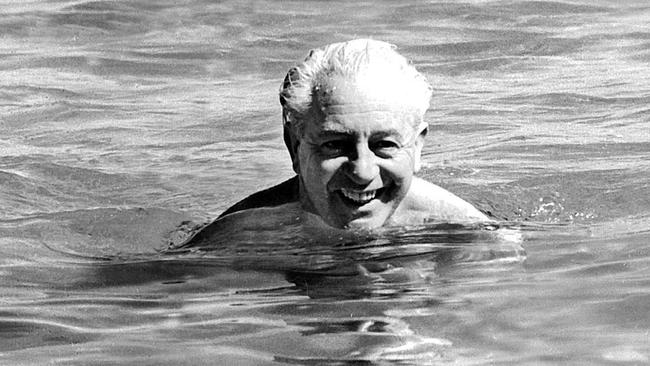

Yet Kendell’s career soared after the media captured a picture of Nixon and Khrushchev drinking Pepsi together, and he became the CEO in just six years.

The global publicity, especially in an untapped market as large as the Soviet Union, propelled Kendell to the highest ranks of PepsiCo and tied his legacy to that of Richard Nixon’s.

Breaking Into The Soviet Market

The pair worked together to reignite Nixon’s political career throughout the 1960s, leading to his election as president in 1968. The close connection between Nixon and Pepsi became clear when Nixon used his political connections to broker a deal with the Soviets.

Pepsi would be offered as the sole American soda in the Soviet bloc, shutting out Coca-Cola, and the United States would sell vodka made by the Soviets. Later on, Pepsi would also obtain tomato sauce from the Soviets through trade, which it used for its subsidiary Pizza Hut.

These trade deals were part of the broader easing of tensions that Nixon strove to promote during his presidency, but they also made Kendell and Pepsi rich.

The process through which the parties traded drinks was complicated. Since the Soviets were closed off from the world economy, trading international currency was impossible.

This forced Pepsi to effectively barter with the Soviet Union, specifically trading goods one-for-one rather than conducting a financial transaction. This pattern of bartering became the norm for Pepsi when dealing with the Soviets, setting the stage for alternative products being traded.

On the Soviet side, trade offered the opportunity to interact with the outside world without fully opening the economy. Western powers were eager to access the untapped market of the Soviet Union, while the Soviets sought access to technology that was more advanced than what they currently owned.

Soviet leaders hoped that Pepsi would be a gateway to other trade deals, a simple trade of soda for vodka that would encourage other Western companies to negotiate for things like mining equipment, automobiles, and other advancing technologies.

However, as Nixon’s presidency passed, so did the positive relationship between the two powers. Public opinion once again turned on the Soviets, making it difficult for Pepsi to sell the vodka they obtained through their trade, and the trade offers the Soviets had hoped for hardly materialized.

But, Pepsi continued to grow in the Soviet Union, proving that their product was more popular; this resulted in 16 bottling factories being established by 1985, when Mikhail Gorbachev came to power in the USSR, demonstrating the capability and potential of Western investment in the Soviet market.

Under Gorbachev, the Soviet Union began breaking down the walls that separated it from the outside world, and brands such as McDonald’s began taking advantage of the untapped potential by opening locations in Moscow and other Soviet cities.

This provided Pepsi with even more political power as the Soviet market grew, and they aired ads declaring they were responsible for the Soviets opening their culture to the West.

How Did Pepsi Get A Navy?

Then, in 1989, Pepsi switched out the vodka for military vessels. The company promised to sell more soda within the Soviet Union and open a number of Pizza Huts in return for a trade that involved 17 submarines and 3 warships.

In the brief period that the company owned the ships, they could have been considered tied for the 6th largest naval force in the world, tied with India at the time.

Realistically, the ships were all in terrible condition; they were all aged and falling apart, and the Soviets only sold them because they wanted to stockpile international currency by selling scrap metal. Knowing that the ships were not pragmatically useful, Pepsi immediately sold them to a Norwegian shipbreaking firm.

The company then orchestrated a contract, partnering with the firm to craft a deal with the Soviets that aided in the Soviet construction of new ships. As a result, Pepsi got to invest in the growing Soviet market both directly with its brand as well as by investing in a company assisting with Soviet production.

This came at a particularly good time for PepsiCo., since it was fighting a brand war with Coca-Cola. The latter had recently re-released its original flavor after a rebranding strategy went wrong, and the marketing campaign was an immense success.

Pepsi’s monopoly in the Soviet Union also ended in 1985. This forced Pepsi to find a way to assert its dominance in the international marketplace.

Pepsi After The Cold War

While the Pepsi Navy never existed as an armed force, it represents Pepsi’s adept ability to navigate international relations under Kendall. The ideological conflict at the center of the Cold War had all but concluded by 1989, and the Soviets were entering the global stage, preparing to become a capitalist country.

The Pepsi company understood that assisting the Soviets with their goal of obtaining more foreign currency would allow them to integrate further into the global economy, bolstering Pepsi’s place in the Soviet market as it continued to grow.

Unfortunately for Pepsi, the Soviet Union disbanded shortly after; however, Russia is still the third-largest market in the world for Pepsi, proving that their investment over four decades still pays dividends.

As with any odd story, it is difficult to find any evidence that the Pepsi Navy ever really existed at all. The main supporting evidence for the story is an article written in the New York Times in May of 1989, which briefly mentions the warships in passing in an editorial.

A later article about a large Pepsi and Soviet Union deal in 1990 makes no mention of the ships, likely because the deal was brief.

A post by a user named “bean” criticizes the story, claiming that one editorial is not enough proof that the ships exist, insisting that historical naval records make no mention of the ships that were sold to Pepsi.

However, an article written by Professor Paul Musgrave in Foreign Affairs reasserts the truth of the matter as he claims to have unique sources that confirm the validity of the story.

Whether the story is true or not, Pepsi had an undeniable effect on international relations during the Cold War. The Soviet economic sphere would not have opened as easily or quickly without Pepsi’s dealings with the communist country, and the two had already bartered.

It is not a far leap to assume the Soviets wanted to leverage their positive relationship with a Western corporation as a way to get quick cash, even if it made Pepsi the 6th largest navy in the world.

Leave a comment