When it comes to carrying out a bank heist, one of the more important aspects the perpetrator needs to keep in mind is to ensure they successfully hide their face.

Surprisingly, this small but important aspect of a successful heist has sometimes been overlooked by would-be masterminds.

In 2007, a man from New Hampshire walked into a bank with branches and leaves taped to his head in order to disguise himself. He got away with some cash but was quickly recognized when the CCTV footage was released to the public.

In Iowa in 2009, two men drew fake beards and glasses on their faces with permanent markers before trying to break into apartments. They believed that drawing on their faces would make them unrecognizable to witnesses.

Their swift arrest proved their theory wrong.

Then, in 2020, two men tried to rob a convenience store in Virginia wearing hollowed-out melons on their heads to conceal their identity. Unsurprisingly, the duo were soon caught.

Even more bizarre than these three cases could be the story of McArthur Wheeler.

He didn’t wear a mask or face covering when committing a bank robbery because he felt he didn’t need to; a simple dash of lemon juice on his face would render him invisible to security cameras. Or so he thought.

His belief was wildly incorrect, and the cameras certainly did pick up a clear picture of his face when he carried out the crime.

However, this story is more than just a bizarre tale of an overconfident—and highly misadvised—criminal.

The tale of McArthur Wheeler also led to the creation of what we now know as the Dunning-Kruger effect, a psychological principle explaining how people with limited knowledge or capability tend to overestimate their abilities.

How the Lemon Heist Unfolded

The bizarre case began with McArthur Wheeler’s flawed idea: that applying lemon juice to his face would make him invisible to security cameras.

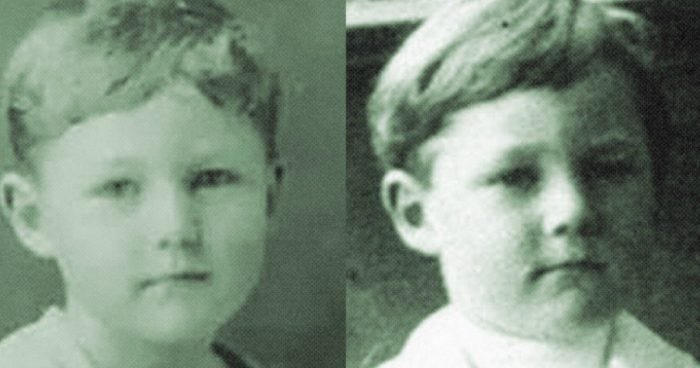

While this incorrect belief firmly held by McArthur is bizarre enough, even more peculiar is how his friend convinced him it was true.

McArthur’s friend and fellow crook, Clifton Earl Johnson, told him of the unusual trick he’d discovered to avoid detention from security cameras.

It was science, Clifton told his friend: lemon juice was nature’s invisible ink.

In a bid to see if Clifton was correct, McArthur squeezed the juice of a lemon and dabbed it to his face. Without the ability to check himself on film, he used his Polaroid camera to take a selfie and analyze the result.

If his face were invisible in the picture, he’d concede that his friend was right and that lemon juice did make your face vanish.

Sure enough, when McArthur looked at the image he’d just taken of himself, the lemon juice had indeed made his face undetectable. We can never know what caused the Polaroid to come out with this result.

Perhaps McArthur hadn’t taken the picture at the correct angle, maybe it was blurry, and therefore, he mistook it for the effects of lemon juice, or maybe the film was faulty.

Regardless, he felt he had discovered a hack to ensure CCTV never captured him again.

He and Clifton planned to rob two banks using their lemon juice masks. They thought their plan was foolproof.

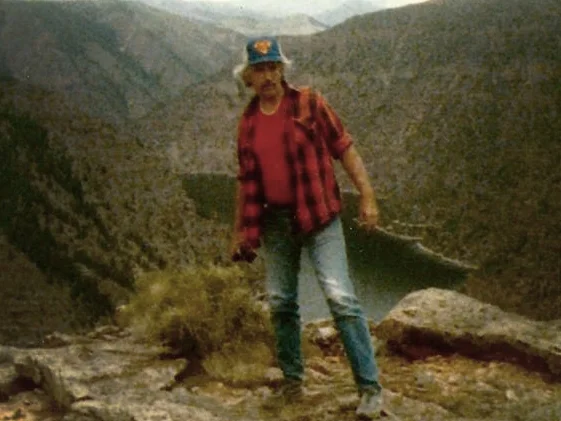

On January 6, 1995, the pair donned their guns and set about carrying out their scheme.

Their first stop was a local bank in Pittsburgh, where the pair boldly entered without any form of conventional disguise, their faces clear as day for all—including the security cameras—to see.

McArthur approached the teller, demanded cash, and made off with the stolen money.

No effort was made to conceal his identity, and the men left the bank believing that the cameras had captured nothing but a blur where their faces ought to be.

Emboldened, the duo moved on to a second bank. Again, neither man wore a mask or tried to hide their face in a meaningful way.

Once again, McArthur demanded cash and quickly left with the money.

Unbeknownst to the pair, both banks had captured clear footage of McArthur’s face, and law enforcement set about distributing the images.

Clifton was arrested first, and McArthur was arrested months later, in April.

The latter was genuinely shocked at the police being able to track him down. Upon his arrest, McArthur allegedly protested, “But I wore the juice!” as the cuffs were placed on him.

In his outburst of disbelief, he’d also just inadvertently admitted to the crimes he was accused of.

His confusion also served to demonstrate the extent of his misplaced confidence.

The story became light-hearted news, with the duo the butt of many jokes for their stupidity.

However, an unexpected aspect of their crimes was that they led to the creation of what we now know as the Dunning-Kruger Effect in psychology.

How the Dunning-Kruger Effect Was Created

In the aftermath of McArthur Wheeler’s crime, amid the comic relief it gave both law enforcement and the public, social psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger looked deeper into the criminal’s behavior.

After all, to assume that lemon juice would render you invisible on camera could be considered an absurd belief. Even more inane was the fact that two men of average intelligence would use this incorrect belief to rob banks.

The baffling nature of the case was something David and Justin wanted to get to the bottom of.

The two psychologists were already looking into the effects of cognitive biases that can shape human behavior when the McArthur case hit the headlines. The story fit perfectly into what they were trying to research.

The case gave them an extreme exploration into where individuals with limited knowledge or competence in a particular area overestimate their abilities.

Simply put, their research found that people who know the least are often the most confident because they lack the knowledge to recognize their own mistakes or faults.

The main study in their paper on the topic was McArthur Wheeler himself, for believing he could make himself invisible with lemon juice.

For reasons unknown, the paper neglected to include McArthur’s accomplice, Clifton, despite him also believing that lemon juice makes you invisible.

The psychologists’ research found that McArthur fully convinced himself that lemon juice had magical properties because he lacked the necessary knowledge to challenge his assumption.

The resulting overconfidence, which results from not having enough knowledge to reach the correct conclusion, is the now-named Dunning-Kruger Effect.

The paper mentions that there are plenty more people like McArthur Wheeler in the world, and they can often have high-profile jobs, such as working in politics or banking.

They found that underqualified individuals often overestimate their capabilities, while more knowledgeable individuals remain doubtful of their skills.

Since the late 1990s, the Dunning-Kruger Effect has been recognized as a critical tool for psychologists and educators worldwide.

Although a big part of its creation is the comic tale of a man who believed he could disguise himself with lemon juice, there’s no denying that the research into McArthur’s case has had a lasting impact on psychological research.

Where is McArthur Wheeler Now?

McArthur Wheeler was charged with multiple counts of robbery and sentenced to 24 years behind bars. He had been implicated in bank heists in the years prior to his arrest, but these charges were dropped before he stood trial in 1996.

Details about McArthur’s life after his conviction are scant. As of writing, some believe he is still incarcerated, some believe he got paroled, and others suggest he may have passed away, citing an obituary for someone with his name dated 2015.

Though McArthur laid low throughout his incarceration and beyond, he will forever remain tied to one of the most bizarre cases in recent history.

Although his accomplice, Clifton, did not receive the same publicity as his counterpart, his role in the heists was still significant. He, too, was convinced of the lemon juice’s “invisibility” effect, which led him to follow McArthur into the robbery attempts despite his obvious lack of rationality.

Clifton was also sentenced to a prison term for his involvement in the heists. He received a slightly lesser sentence compared to McArthur, but both were convicted on charges of robbery and conspiracy. Few details have emerged about his time in prison or his life afterward.

It’s likely he has since been released and hasn’t been in trouble with the law since.

Sources

https://www.newspapers.com/article/centre-daily-times-lemon-juice-didnt-wo/111378933

https://qz.com/986221/what-know-it-alls-dont-know-or-the-illusion-of-competence

https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/06/20/the-anosognosics-dilemma-1

Leave a comment