During the final months of World War Two, the victorious Red Army was steamrolling throughout eastern and southern Europe. As it advanced, it captured millions of Axis soldiers, including thousands of Hungarians.

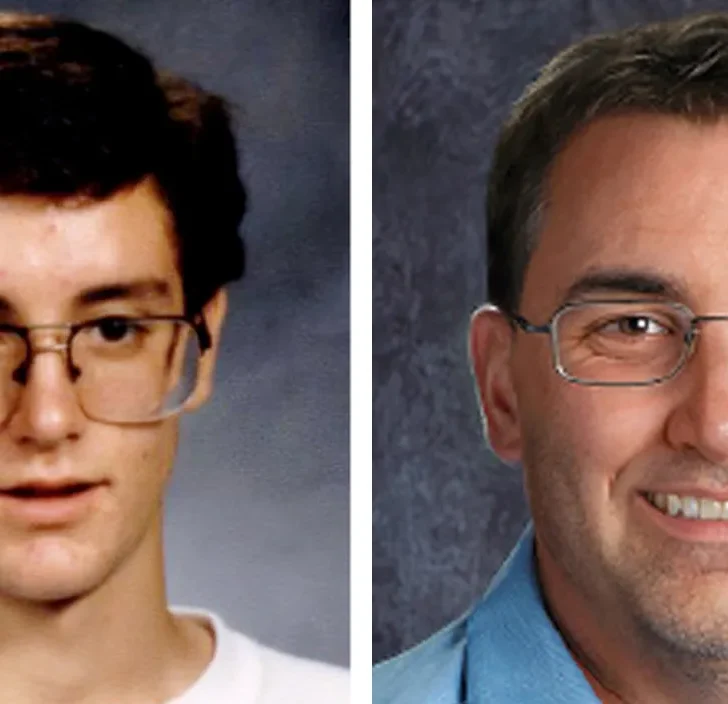

Among these Hungarians was an unknown private by the name of Andras Toma.

Though obscure at the time, little did he know when he fell into Soviet hands at the end of 1944 that this would be the beginning of a decades-long odyssey for him that would end with Andras setting the record for the longest time someone has been a prisoner of war.

Background

Due to the poor record keeping of the rural region Andras grew up in and the chaos of the war at that time, little is known about him up until his conscription into the army.

He was born in Újfehértó and grew up in the little village of Sulyanbokor. Andras had a mother and father and two half-siblings from his father. At the time of his capture in 1944, his brother was seven, and his sister was just one year old.

It is known from Andras’ interviews that he attended at least some schooling. However, it appears he left school early to become a blacksmith apprentice. By the time Andras had begun blacksmithing, the tide of the war had not been going well for Germany and her allies.

By the summer of 1944, the German military and its allies suffered their worst defeat of the war. During Operation Bagration, the Soviet army annihilated the center of the Eastern Front.

As a result, the rest of Eastern Europe was now wide open. As Soviet troops poured into Romania and Bulgaria, the two allies switched sides and declared war on Germany.

Hungary was going to do the same until a Fascist coup supported by German forces instilled a pro-German dictator under the Hungarian equivalent of the Nazi party, the Arrow Cross party.

Once the Arrow Cross party took control of Hungary in October 1944, the new government began a wave of general mobilization that saw every fit male aged 14 to 70 being called up for military service.

During this time, army recruiters came to visit Andras at his family home to conscript him into the army.

Capture And Prison

Due to the vast numbers of Hungarians thrown into the army at this time, along with the enormous levels of destruction, adequate records are not known to exist of Andras.

However, later interviews with him highly suggest that he served in an artillery regiment. This is because of how he talked about canons firing and his knowledge of artillery that a regular infantry soldier would not know.

He also said the standard infantry cap badge on a period Hungarian army cap was not his badge. But he would not elaborate on what his badge looked like.

Because of this, it is best inferred that he was conscripted in October 1944, was trained to help fire artillery for the Hungarian army, and was thrown into battle along with his father.

It is not known precisely when he was captured, but Soviet records state he was captured near the Polish city of Krakow.

Since Krakow was not liberated until January 19, 1945, and the earliest record the Soviets have of him is at a prisoner of war camp near Leningrad at the end of January 1945, Andras probably fell into Soviet hands sometime between December 1944 and January 1945.

Once Andras was in Soviet captivity, it was then that it appears his nightmare really began. Though he had survived some of the hellacious final battles of World War Two, he was not out of the woods yet.

Transportation from the front lines to a Soviet POW camp was not easy. The Soviet troops packed dozens of prisoners inside tiny, unheated box cars.

As the train continued slowly towards the Soviet Union, men inside Andras’ car began dying from the cold, untreated wounds, and sickness.

During the several-week journey to Leningrad, Andras remembers having to sleep on the dead bodies of his former comrades since there was nowhere else to go. This experience clearly began to affect him by the time he arrived at the first POW camp near Leningrad.

When a Soviet officer began filling out his questionnaire, he recorded his name as Andras Tamas. This, of course, was not his actual name. Why his name was recorded differently is lost to history.

But considering that Andras was barely speaking by this point, he may have just mumbled something; the officer wrote it down, and that was it. Little did Andras know that a tiny mistake would cost him his life.

For the next two years, Andras was kept in at least one other POW camp. By 1947, though, he was recorded as having a kind of psychosis and sent from the POW camp to a rudimentary psychiatric hospital near Kotelnich, Russia. It was here that this would be his home for the next 53 years.

Hospital Stay And Discovery

Once Andras was at the psychiatric hospital, he was stuck with no one to talk to. During his initial period of captivity, he was one of the few Hungarians in a nearly all-German camp. He also did not pick up on any Russian. As a result, Andras could not communicate.

Combining this with the fact that he suffered from schizophrenia, Andras’ ability to intelligently communicate with other people was basically zero.

Because of his inability to communicate, any attempt by him to advocate for his release was impossible. The Hungarian government did investigate his disappearance.

However, when they sent his name on the list of potential Hungarian POWs, the Soviet authorities stated they did not have him on their list. This was true since Andras Toma was now Andras Tamas in Soviet records.

When the last group of Hungarian POWs was released in 1954, and Andras was not among them, he was declared legally dead by a Hungarian court. Andras did not legally exist from then on, except he did not know that.

For the next five decades, Andras languished at the hospital. During this time, he suffered an unknown medical condition that forced doctors to amputate his right leg to save his life. But besides that, the staff there had little interaction with him.

Though many tried over the years, few staff members ever attempted communication since his consistent rambling in his older dialect, Hungarian, was just seen as gibberish and a symptom of his schizophrenia. That is until a visiting Slovak doctor recognized what it really was.

In 1997, a Slovakian doctor was visiting the hospital. Among the patients she saw was Andras. Others had told her they could not get him to talk.

As she listened to the mumblings he was saying, the doctor quickly realized that not only was it an actual language, but she could understand it.

Having grown up close to the border with Hungary, she recognized that what Andras was speaking was a nearly extinct Hungarian dialect.

Astounded at her discovery, she alerted the hospital administration, who contacted the Hungarian embassy.

Once the Hungarian embassy became aware of Andras, the Hungarian military attaché was immediately dispatched to interview him. What Andras said was surprising.

Andras Goes Home

As the Hungarian military officer interviewed Andras, he was surprised at how much he spoke and what he was saying.

Though they did not have a record of his Hungarian citizenship, his conversations with the officer proved his knowledge of Hungary since he could name people he knew from his village, as well as his teachers from school and his service in the army.

A group of psychologists soon went to interview Andras as well. They confirmed his schizophrenia diagnosis as well as his ability to speak an outdated dialect of Hungarian.

With all of this evidence, the Hungarian government made an official plea to the public that anyone who might have a long-lost relative from the war should submit samples for DNA testing.

Among the six hundred families who sent in DNA samples was Andras’ sister. Though her husband initially discouraged her, she thought this could have been her long-lost brother. After all, it was worth a shot.

When the DNA results came in, it was scientifically proven that Andras Tamas was actually Andras Toma and that his sister and brother were alive and well all these years later.

After confirming his identity, Andras was finally brought home to Hungary to a hero’s welcome.

As part of the government’s way of taking care of Andras for the 56 years he spent in captivity, they awarded him 56 years of back pay as a private in the Hungarian army and a promotion to Sergeant Major plus the pension that came along with that promotion.

But no amount of money could undo the suffering Andras had endured.

His sister Anna later recounted that he still refused to talk to anyone the first few weeks he was back. However, he slowly began rebuilding his trust in her and her family.

Andras then picked up a hobby of repairing farm implements on the family property and caring for the flowers. He helped her prepare meals by peeling vegetables and other tasks around the house.

Andras developed his desire to talk again and constantly laughed and joked with everyone, including strangers. Unfortunately, this would not last long.

Not even four years after Andras returned home, he passed away of natural causes. Over two thousand people attended his funeral, and he was buried with full military honors.

But how did this travesty of justice happen?

Conclusion

Andras Toma was one of World War Two’s many victims. After being forced to fight a war he did not want, he endured unspeakable cruelty both in prison camps and in hospital.

Forgotten to time due to the carelessness of Soviet bureaucracy, as well as having no one to advocate for him in Russia, he spent almost his entire life a prisoner.

Perhaps the only silver lining in this story is that at least he died a hero in his country surrounded by those who loved him, and his story can be a cautionary tale of the due diligence needed to care for prisoners during times of war.

Sources

https://web.archive.org/web/20110612041040/http://www.mno.hu/portal/12663

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2000/sep/19/1

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2001-oct-28-mn-62435-story.html

https://thehistoryfiles.com/hungarian-armed-forces-1944-45-i/

https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/last-pow-laid-to-rest-in-hungary-1.494247

Leave a comment