The name D. B. Cooper has become part of the true crime folklore of the 20th century. This unknown hijacker and his fate have become the subject of intense debate.

But who was he, and what really happened to him?

The story has often been recounted, but even basic facts have become distorted and confused over the years. Even the name D. B. Cooper seems to have come from a mistake made by a reporter.

Here’s what we actually know about this mystery man and events that took place in the winter of 1971 and since.

The Hijacking

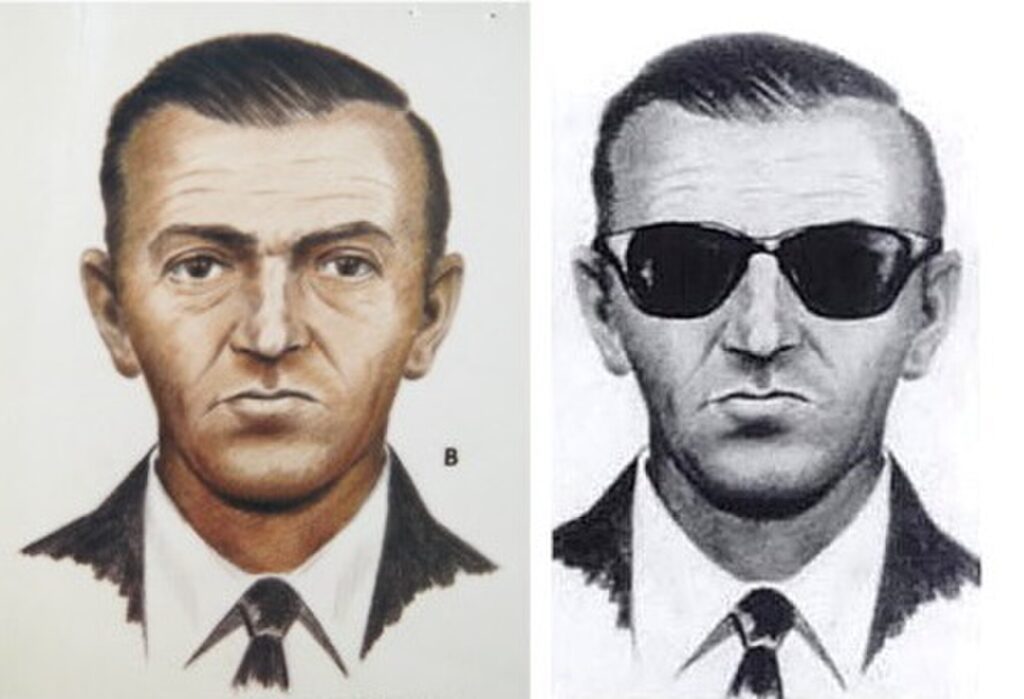

On the afternoon of November 24th, 1971, the day before Thanksgiving, a man approached the Northwest Orient Airlines desk at Portland International Airport, Oregon.

He paid $20 in cash for a one-way ticket on Flight 305 to Seattle, Washington. No ID was required for domestic flights, but the man gave his name as “Dan Cooper.”

Staff at the desk would later confirm that the man appeared to be in his 40s, around six feet tall, was wearing a dark business suit, a shirt and tie and carrying a small attaché case.

They, and other witnesses, would say that the man seemed perfectly calm and had no distinctive features or obvious accent. He was “nondescript”, and nothing made him stand out from other passengers.

Cooper, along with the other 36 passengers on Flight 305, boarded the plane. He took his seat, 18C, an aisle seat near the rear of the Boeing 727-100 aircraft.

The flight crew, comprising the captain, co-pilot, flight engineer and two flight attendants, prepared the aircraft for its short flight, eventually leaving the ground on schedule at 16:35.

Cooper had ordered a bourbon and soda almost as soon as he was seated, and soon after take-off, he called flight attendant Florence Schaffner over.

He handed her a folded note. She was busy attending to other passengers and didn’t immediately read it.

Cooper called her over again and told her that she had better read the note as he had a bomb in the attaché case next to him.

Schaffner read the note, which threatened to blow up the aircraft if Cooper was not provided with $200,000 in cash and four parachutes when the aircraft landed at Seattle-Tacoma Airport.

Schaffner showed the note to the Captain, William Scott, who then reported it to Air Traffic Control. They, in turn, informed the police, who reported to the FBI.

The FBI contacted Northwest Orient Airlines President Donald Nyrop, who told them that they should do nothing to endanger the crew or passengers on the flight and that they should meet the hijacker’s demands.

Schaffner returned to speak to the man. He had moved into the window seat, with the attaché case on the middle seat. Schaffner sat in the aisle seat, and the man opened the case to reveal “red sticks and wires.”

He made Schaffner return the note he had given her and told her to inform the captain that the flight must not land at Seattle until the cash and parachutes were ready.

The aircraft circled until the flight crew were told that everything was ready on the ground. When it landed, the man ordered it to taxi to a remote but well-lit part of the airport.

The cash and parachutes were delivered to the aircraft by a Northwest Orient Airlines employee.

The hijacker allowed all 36 passengers and flight attendant Florence Schaffner to leave the aircraft. The other flight attendant, Tina Mucklow, remained aboard with the other three flight crew members.

Cooper demanded that the aircraft be refuelled and prepared for a flight to Mexico City. At around 19:45, it took off.

The Escape

The hijacker gave very precise instructions for the flight. The aircraft was to fly at no more than 150 knots (close to the minimum speed at which it could safely fly) and at no more than 10,000 feet and with the main cabin depressurised.

Captain Scott warned that the jet could not reach Mexico City without refuelling at this speed and altitude. The hijacker agreed that it could land at Reno, Nevada to refuel.

Tina Mucklow was told to remain in the cockpit with the flight crew after the hijacker asked her how to operate the aircraft’s rear stairs. Fifteen minutes after take-off, a red light in the cockpit warned that one of the aircraft’s access doors had been opened.

At 20:25, the aircraft suddenly pitched forward as the plane passed over open country around 25 miles north of Portland, Oregon.

The flight crew and Tina Mucklow remained in the cockpit as instructed.

When they landed at Reno, they found that the rear stairs had been lowered during the flight (causing the aircraft to pitch forward), that there was no sign of the hijacker, the money or the attaché case, and that one of the parachutes was missing.

There was only one possible conclusion: the hijacker had made his escape by jumping from the aircraft during its flight.

The Search

The FBI immediately launched one of the largest and longest investigations ever, NORJAK (Northwest Hijacking). By 1976, they had interviewed over 800 potential suspects, but none were positively identified as the hijacker.

They also looked at people named “Dan Cooper” just in case the man had used his real name. They didn’t find anyone who matched, but they mentioned one man who had been interviewed and eliminated at a press conference.

That man’s initials were “D. B.” and a reporter mistakenly thought that was the alias used by the hijacker. From then on, the hijacker was popularly known as “D. B. Cooper”, though he never actually used that name.

An extensive police search of the wooded and rugged area where Cooper was thought to have left the aircraft was carried out in the following weeks and resumed the following spring, but no trace of Cooper or the parachute was ever located.

The FBI did find what seemed to be a good suspect in 1972 when there was another very similar hijacking of a US airliner.

In April 1972, a man armed with a pistol and a hand grenade took control of another Boeing 727.

This time belonging to United Airlines and on a flight to Denver, Colorado. Just like Cooper, the hijacker ordered the aircraft to land and that $500,000 and four parachutes be delivered to it.

He then parachuted from the aircraft over Utah. Three days later, the FBI arrested that hijacker, Richard McCoy Jr., at his home in Utah.

The similarities between the hijackings raised the suspicion that McCoy was Cooper. Still, there was a major problem: witnesses who looked closely at Cooper on the day of the hijacking were certain that McCoy wasn’t the same man.

McCoy was shot dead in 1974 by FBI agents after escaping from prison. The FBI decided that he wasn’t Cooper (though some disagreed) and that this was a copycat crime inspired by the Cooper hijacking. They did not identify any other viable suspects.

Who Was Dan Cooper?

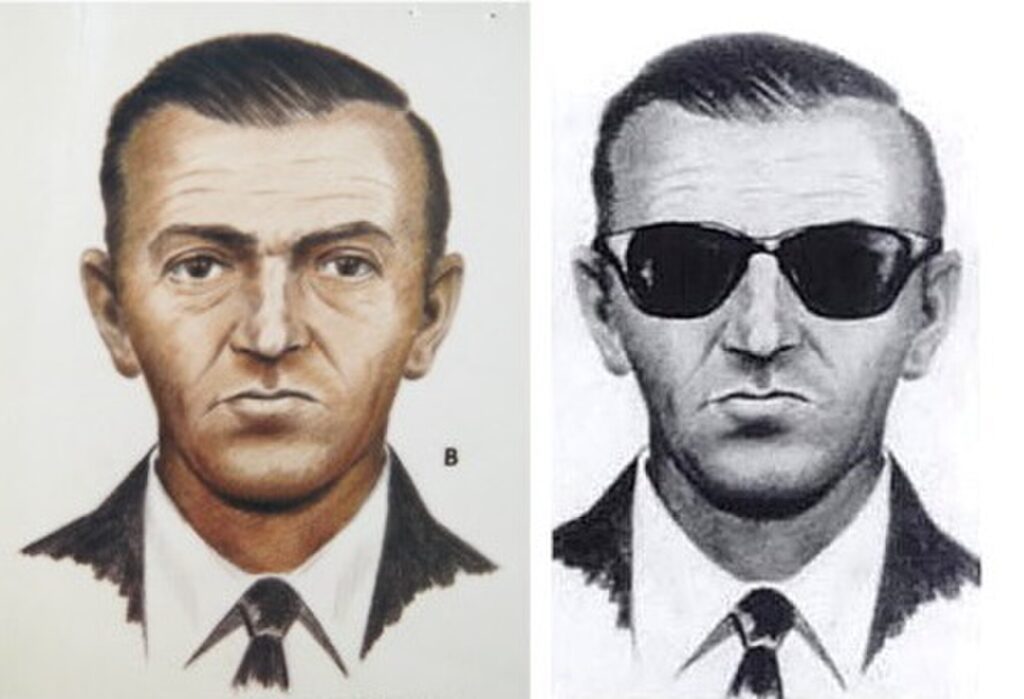

We have a good description of Dan Cooper’s physical appearance because flight attendants Florence Schaffner and Tina Mucklow observed him at close range over an extended period and in good lighting.

Their descriptions agreed with one another and with those provided by Northwest Orient Airlines staff at Portland. Both were certain that Richard McCoy Jr. wasn’t Dan Cooper.

Cooper did seem to have a very detailed knowledge of the Being 727-100.

He knew how long it should take to refuel the aircraft, and he appeared to know that the rear passenger steps could be lowered in flight, something that even the experienced flight crew weren’t aware of.

He seemed to know about parachutes too, insisting that those provided were civilian versions (with ripcord handles) and not military issue, which generally have some form of automated opening.

He was also methodical. When he left the aircraft, he took with him not just the ransom money but the case that may (or may not) have contained a real bomb and even the ransom note.

The only thing that he left behind was a clip-on tie with a small tie-pin. The FBI carefully examined both, but they failed to provide viable leads. Instead, the FBI began to look for other clues to the identity of the hijacker.

Was he an experienced skydiver? That’s something that has caused a great deal of debate.

Some people have said that he must have been, while others have noted that no experienced parachutist would have attempted to jump from an aircraft traveling at 150 knots (much faster than most skydiving aircraft), over rugged, wooded terrain and in the dark.

Did he die on 24th November 1971? That certainly seems possible, and it’s notable that even if he had survived the jump, he would have landed in a remote area in winter, wearing only a business suit and casual loafers, hardly the ideal outfit to survive in the open.

A body might certainly have remained hidden in the rugged terrain over which he jumped, but in that case, it does seem a little strange that his parachute wasn’t found despite a long and intensive search on the ground and from the air.

Why did he call himself Dan Cooper? This too has been the subject of debate.

It has been pointed out that since 1954, Tintin magazine featured a series of popular stories under the title Les Aventures de Dan Cooper, comic strips about a daring test pilot in the Royal Canadian Air Force who, in a number of adventures, parachutes from aircraft.

Was this the inspiration for the hijacker’s alias? Like so many aspects of this story, we simply don’t know for sure.

One more clue emerged in 1980 when a family who were enjoying a camping trip near the Columbia River, north of Portland, found a package containing almost $6,000 in partially rotted $20 bills.

The serial numbers of the bills handed over to the hijacker of Flight 305 were recorded by the FBI, and a check confirmed that this package had been part of that ransom payment.

None of the other bills handed to the hijacker have ever been discovered in circulation.

Conclusion

Many suspects have been identified over the years as being Dan Cooper. However, none have been positively identified, and witnesses who saw Cooper have not agreed that any of these suspects were the hijacker of Flight 305. The FBI case remains open.

Presumably, the motive for this crime was the $200,000 obtained as a ransom (worth around $1.5 million in current value).

But none of the $20 bills handed over by the FBI have ever turned up other than for the package found near the Columbia River in 1980.

This strongly suggests that Cooper was never able to spend the ransom money, and that, in turn, indicates that perhaps he didn’t survive jumping out of the airliner.

But if he died, you would imagine that it would have been relatively easy to identify a man matching his physical description who abruptly disappeared on 24th November 1971. To date, no such person has been found.

The only unsolved airliner hijacking in US history remains a baffling mystery.

Maybe one day, a backpacker may stumble across a parachute or human remains in the remote forests of Oregon, or perhaps some of those ransom notes will turn up in circulation.

Until then, we can only speculate about who Dan Cooper was and what happened to him in November 1971.

Sources

https://www.fbi.gov/history/famous-cases/db-cooper-hijacking

Leave a comment