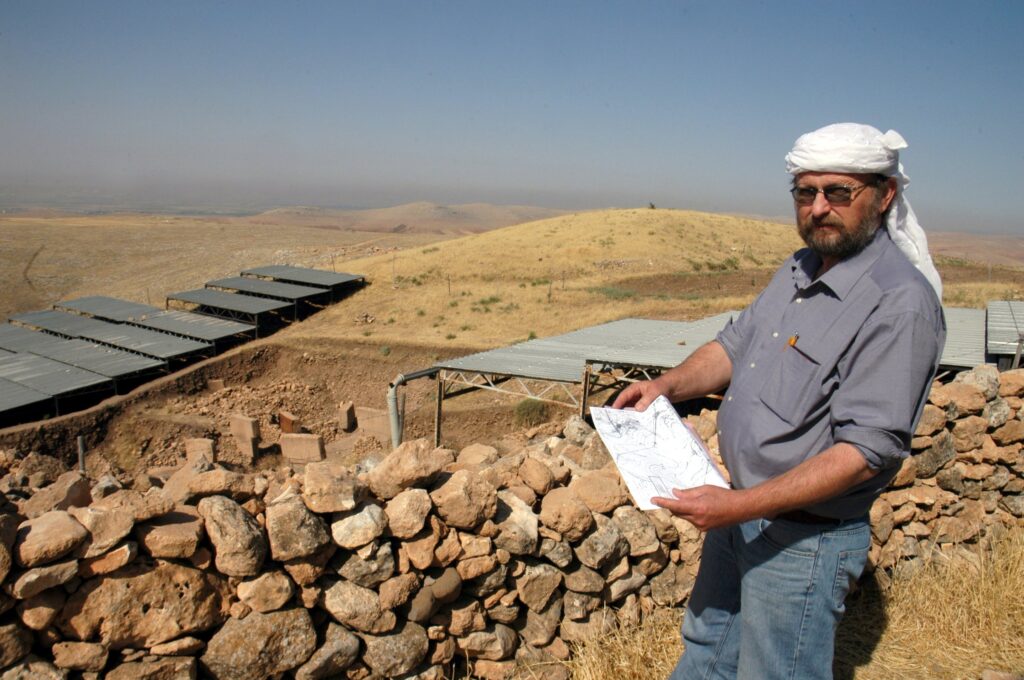

In 1994, Klaus Schmidt, a German archaeologist, almost by accident, first recognized Göbekli Tepe in southern Turkey as a site of great archaeological significance.

Schmidt and his team began excavations a year after he was first introduced to the site, and what they found changed, by thousands of years, the accepted timeline for the birth of organized human religion.

A Shepherd Makes A Discovery

While tending his flock across a landscape of arid hillsides, a Kurdish shepherd walked past a very old mulberry tree which locals believed to be sacred, and just as he passed the tree, he heard the bells on his sheep tinkle, and when he looked down, he saw something in the sand.

When the shepherd brushed away some of the sand, he discovered a large, oblong stone. After spotting this strange stone, the man looked around, and he noticed several more stone rectangles peeking above the sandy surface.

The old shepherd thought that he might have found something important, so he decided to tell someone about what he had seen as soon as he returned to the village.

A few weeks after the shepherd had spread the news about his discovery in the desert, museum curators in the ancient city of Sanliurfa, ten miles southwest of the stones, heard the shepherd’s story.

The museum then contacted the German Archaeological Institute in Istanbul, and in late 1994, archaeologist Klaus Schmidt visited the site of Göbekli Tepe.

Schmidt once said, “As soon as I got there and saw the stones, I knew that if I didn’t walk away immediately, I would be there for the rest of my life.”

Hunter-Gatherers Practiced Organized Religion?

As Klaus Schmidt and his team started to reveal some of the buried secrets at Göbekli Tepe, they discovered that the site was vast, and that it had been built roughly 12,000 years ago, which means Göbekli Tepe was built 7,000 years before Stonehenge or the pyramids of Giza.

The carbon dating of the structures at Göbekli Tepe at over 12,000 years old, meant that these structures were built prior to the advent of basic metal tools, or even pottery, and well before any system of writing had been developed.

Schmidt soon discovered that the site was a very large complex, with a number of temples. These temples were circular stone enclosures which contained large, intricately carved pillars, each weighing as much as 10 tons.

These pillars featured detailed carvings of bizarre images of stylized humans with very long arms, as well as many carvings depicting wild game animals, such as boars and ducks. Other pillars featured serpents, crayfish, or lions.

Schmidt discovered more than 20 of these circular stone enclosures, or temples, the largest of which was 20 meters across, with two massive, carved pillars at its center.

Göbekli Tepe is located in an area rich in natural limestone, which is soft enough to be worked with wood or stone tools, but Schmidt’s team was astounded by both the scope of the work and the intricacy with which the carvings at the site were created using these simple tools.

Schmidt found many stone tools at Göbekli Tepe, and while he also found a large quantity of animal bones, he didn’t find any evidence of either domesticated animal species or domesticated plants or grains.

For Schmidt and the entire world of archaeology, this discovery threatened to completely change the way that the field viewed both the history of religious practice and human history in general.

Prior to the discovery of Göbekli Tepe, it was widely accepted in the archeological community that people did not develop ritual and religion until they had domesticated crops and animals.

But in his 25 years of excavation at the site, Schmidt never found any evidence of the domestication of animals or of farming, yet Göbekli Tepe was a large, complex temple site.

A New View Of The Origins Of Organized Religious Practice

After the discovery of Göbekli Tepe, Klaus Schmidt spent the rest of his archaeological career at the site.

As the years passed and the excavations continued, Schmidt and many others in the archaeological community drastically changed their views on how and when humans began to practice organized religion.

There appeared to be wide consensus that Göbekli Tepe had changed the game. In 2009, Stanford archaeologist Ian Hooder told the Daily Mail, “‘Göbekli Tepe changes everything.”

The entire academic community was quickly shifting from the view that humans could not develop the organized practice of religion until after they had given up the nomadic lifestyle of the hunter-gatherer.

It had been believed that humans first needed to begin to domesticate animals and crops, and then move into more permanent shelters in stable communities, prior to developing anything like organized religious practices.

However, because of his work at Göbekli Tepe, Schmidt believed that the nomadic people who traversed the area would gather at times to work on the site.

Without having found any evidence of permanent settlement or farming, Schmidt was certain that Göbekli Tepe was a ritual site built by the nomadic people of the region.

The thought that Stone Age hunter-gatherers could have built something like Göbekli Tepe appeared to demonstrate that the old hunter-gatherer life, in this region of Turkey, was far more advanced than anyone could have conceived; it had to have been incredibly sophisticated to carve and move these massive pillars in the desert.

By 2007, Schmidt believed that Göbekli Tepe could explain the reason that humans first started to farm and to begin living in permanent communities.

He thought that nomadic people from across the region shared enough of a belief system to join together at certain times to work on the building projects, and perhaps hold communal feasts and celebrations.

However, Schmidt believed that the nomadic groups would part ways after working on the site. He argued that Göbekli Tepe was a ritual site and perhaps a burial site of sorts, but he still had found no evidence of a settlement at the site, so he liked to call the complex “a cathedral on the hill.”

With all of the evidence of nomadic stone-age people creating Göbekli Tepe being uncovered, the long-held consensus that organized ritual and religious practice could only exist when societies began domesticating crops and animals was turned on its head.

While it was believed that only after a people had a food surplus could they devote their resources to rituals and building temples, Schmidt said that Göbekli Tepe demonstrated that complex ritual and social organization actually came before settlement and agriculture.

Schmidt came to believe that over 1,000 years, the needs of the nomadic people who came together in one place to carve and move the huge pillars and build their circular enclosures at Göbekli Tepe, eventually led these people to take the next step in the evolution of society.

The hunter-gatherers needed to have a steady food supply and shelter for people when they gathered in large numbers to work on the temples, so Schmidt argued that the nomads began the process of domesticating animals and plants for agriculture in order to feed and house the temple builders.

Thus, for Schmidt, and nearly the entire archaeological community who was carefully following his progress, the evidence from Göbekli Tepe demonstrated that ritual and organized religion had caused the transition from hunter-gathering societies to agricultural communities.

This discovery turned the timeline for the development of human society upside down.

How Tourism Unlocked the Greatest Secret At Göbekli Tepe

In the mid 2000s, when some of Schmidt’s findings on Göbekli Tepe were more widely published, both colleagues and journalists were fascinated by the work.

Media reports were calling Göbekli Tepe the birthplace of religion, and a German magazine, Der Spiegel, compared the fertile grasslands which had once surrounded the site to the Garden of Eden.

Tourists soon began to flock to the site, and until the war in Syria slowed down the flow of tourists in 2012, excavation work on the site had slowed down drastically for several years because of all of the visitors.

After the threat from the war in Syria subsided, the hillside around Göbekli Tepe was transformed again, and in 2017, the site received a serious upgrade for visitors.

As part of the improvements in 2017, state-of-the-art shelters and coverings for part of the site, along with roads, parking areas, and a visitor’s center, were built, and in 2018, Göbekli Tepe was added as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Klaus Schmidt died in 2014, so he did not live to see either the great expansion of tourism to the area, or the secret which was revealed due to the tourism improvements.

After Schmidt’s death, for the new work to support modern means of both protecting the site and adding protection for visitors, Schmidt’s successor, Lee Clare, had to dig much deeper in order to install the new protective shelters.

While doing this digging, Clare discovered what appeared to be houses and a permanent settlement.

The team also found large rainwater cisterns, as well as cooking tools and unique tools that were used for processing domesticated grains and brewing beer.

Because of the work done to protect the site, Göbekli Tepe gave up its greatest secret. Gobekli Tepe wasn’t an isolated temple that was visited on special occasions. It was part of a thriving village, with large special ritual buildings at its center.

Rather than being an isolated site for the world’s first practice of organized religion, Klaus Schmidt’s successor, Clare, now believes that Göbekli Tepe may be one of the very first villages ever created by nomadic hunter-gatherers.

Thus, it appears that by developing Göbekli Tepe as a tourist destination, the archaeologists, by accident, may have confirmed the original theory that domesticating plants and animals always pre-dated the practice of organized religion.

However, the discovery of this very early village in Turkey, buried deeply surrounding the strange temples of Göbekli Tepe, does reset the timeline for when humans first began to live communally and to adopt farming practices.

With these new insights, Clare and others working on the site do not see the discovery of the ancient village as a repudiation of Schmidt’s theory; rather, they view the new discoveries as the progression of science, built on the shoulders of Schmidt’s work and something that he would have been very excited about.

Sources

https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20210815-an-immense-mystery-older-than-stonehenge

https://www.discovermagazine.com/the-sciences/gobekli-tepe-the-worlds-first-astronomical-observatory

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/gobekli-tepe-the-worlds-first-temple-83613665

Leave a comment