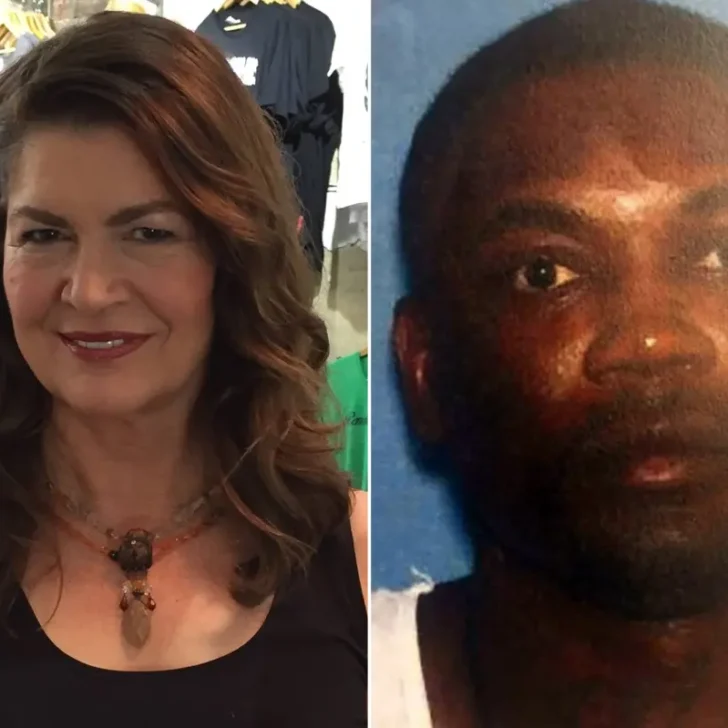

On a hot Sunday morning in Sarajevo, the heir apparent and his wife were on a trip to help mend relations in the empire’s newest holdings. As they traveled in this hostile city, they were unaware of the danger that awaited them.

After being struck down by an assassin’s bullets, the killings set in series a chain of events that culminated in the First World War.

But how did the assassination of an Austro-Hungarian official in a Balkan backwater cause Germany, Britain, France, and Russia to all declare war on one another?

Background

Before delving into the events of June 28, 1914, it is essential to understand what was happening at the time.

In 1914, the situation inside Bosnia and Herzegovina was tense. But to fully appreciate why, one needs to look at the aftermath of the 1877 Russo-Turkish War.

Sensing a way to curry favor with the Slavic people and deal a death blow to the dying Ottoman empire, the Russian Empire supported the independence movement of Christian, Eastern European Slavic peoples who were under the heel of Islamic Ottoman rule.

After fully supporting these independence movements, the Ottoman Empire was dealt a death blow and lost the majority of its European lands and peoples. The countries of Romania, Serbia, and Montenegro all gained their independence.

As part of the Treaty of Berlin after the war, the Austro-Hungarian empire was allowed to occupy the Kingdom of Bosnia, which was still nominally under Ottoman rule but would otherwise be controlled by Austria-Hungary.

The Austro-Hungarians wanted to exert more influence over Bosnia to build a buffer between them and the Ottomans and counter growing nationalist movements in the region.

However, despite the best efforts of the Austro-Hungarians, not all nationalist movements were able to be squashed. In 1903, the pro-Austrian Serbian monarch was murdered and replaced with a pro-Russian one.

Fearful of Serbian influence over Bosnia, which had many ethnic Serbs, the Austro-Hungarian administration officially annexed the region in 1908.

Why Austro-Hungary annexed Bosnia was seen as a way to not only distract the public from internal problems at home but also be able to better legally suppress nationalist movements inside Bosnia now that all the people there were subject to the empire’s laws.

But of course, there were still problems.

By 1911, two terrorist organizations emerged that threatened stability in the region. In Serbia, the Black Hand was formed by Serbian army officers who saw it as their duty to help promote the idea of a greater Serbia.

Inside Bosnia itself, the Young Bosnia movement sprang up. It rose to fame after the 1910 attempted assassination of the Bosnian governor.

From then to 1914, there were seven high-profile assassinations and a dozen attempted plots that targeted Austro-Hungarian officials in the region. It was clear that Austro-Hungarian rule in the region was not well received despite now becoming a part of the empire.

By the spring of 1914, the Austro-Hungarian emperor, Franz Joseph, knew that the administration had to do something to restore relations with the Bosnian people.

He sent his nephew, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, on a public relations tour that summer to give a friendly face to the newly annexed people.

But who was Franz Ferdinand?

Born to nobility by his father, Archduke Karl Ludwig, in 1863, Franz was destined to be in politics and the army but not necessarily ruler of the empire.

However, after the death of his uncle’s only son in a sorted murder-suicide pact in 1889, his father became heir to the throne. When his father passed away in 1896, he became the sole male heir set to inherit the empire.

But of course, he was not well-liked among political circles, not least because he had married below his status to a woman who was not of noble birth.

However, these feelings were not felt by the local Bosnian population. They yearned for independence that was robbed from them in the various treaties that followed the Russo-Turkish war.

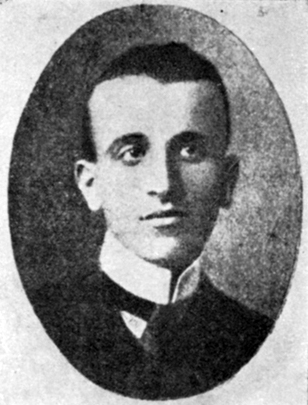

So, when the Austro-Hungarian authorities publicized Franz’s trip that June, one person reading it decided it was time to do his part in the fight for Bosnia’s independence. And that person was Gavrilo Princip.

The Assassination

Princip was a Bosnian of Serbian ancestry. His upbringing was mundane, and the only noticeable part of his past was that his father had served in the Serbian army against the Ottomans during the 1877-1878 Russo-Turkish war.

However, by the time Princip finished his studies in Sarajevo, he had become radicalized as a member of the Young Bosnians.

Though the Young Bosnians were eager to carry out attacks against the Austro-Hungarians, they needed more resources and money to do so.

Thankfully, through contacts established in Serbia, the Young Bosnians found sympathetic members of the Black Hand in Serbia who were willing to support the operation to kill the Archduke as it furthered their own means of creating a greater Serbia.

Throughout the spring of 1914, the would-be assassins recruited other members in Sarajevo as well as got members back from Serbia into Bosnia.

With the help of the Black Hand’s extensive contacts in the Serbian and Bosnian administrations, the group of teenage assassins received a small cache of six pistols, ammunition, bombs, maps, fake identity papers, and cyanide capsules for themselves in the event of capture.

As the Archduke’s visit approached, the local organizer of the group, Danilo llic, proposed this plan. On the morning of Sunday, June 28, the Archduke and his wife Sophie would be driving in a motorcade along the Appel Quay, a major road in the city that ran adjacent to the river.

Because the newspaper publicized the route to ensure eager locals would cheer the Archduke, the group knew exactly where he would be.

Danilo equipped each assassin with either a pistol or a bomb. If one failed, hopefully, others might succeed. With that, the plan was now in motion to kill the Archduke.

On that fateful morning, the Archduke had just finished the last of his review of local army troops. The next part of his route involved going to attend an opening ceremony of a new state museum. In his convoy, there were seven cars that included their security detail, the Mayor, and several aides.

After leaving the military barracks at ten that morning, the convoy passed the first group of assassins. These two failed to act.

However, as they approached the third one further down the street, he threw his bomb at the motorcade. It bounced off the couple’s car and exploded behind them.

Though they were unhurt, the explosion caused over a dozen injuries, and the convoy took off at a high rate of speed to head towards the museum. The remaining three assassins, including Princip, did not act at this time.

Once the Sarajevo Mayor had delivered his remarks at the museum, Franz Ferdinand also gave a short speech, whose printed remarks were stained with blood from the injured, in which he remarked that he was glad the people of Sarajevo had applauded him now despite being greeted with bombs earlier.

Once this had been done, the group contemplated their next move.

Franz’s aides suggested waiting at the town hall until more troops could be brought into the city. The Mayor convinced Franz that there was no further danger, and he agreed.

Franz decided that the entourage would forgo the planned route and head straight to the hospital to check on the casualties from the bombing. However, that word did not make it to the driver of Franz’s car.

As the convoy headed away from the museum, they went back the way they came from on the Appel Quay. But instead of continuing straight towards the hospital, the driver of Franz’s car made a right-hand turn onto Franz Joseph Street.

The driver was quickly reprimanded for his error and told to back up the car to get back to Appel Quay. But as he reversed, the car stalled for a few seconds. This just so happened in front of Schiller’s Delicatessen, where Princip was standing.

In those brief few moments, Princip took his chance. He walked right up to the car, pulled out his pistol, and fired two shots. As he tried to put the gun to his head to kill himself, bystanders wrestled the gun away from him.

The imperial couple’s car took off to head for safety, but it was too late. Franz had suffered a gunshot wound to the neck, and his wife had suffered one to the abdomen. Both were dead within fifteen minutes.

With the heir apparent to the Austrian throne now dead, what was the government’s next move?

The July Crisis

In the immediate aftermath of Franz and Sophie’s deaths, the Austro-Hungarian government was unsure of how exactly to proceed but was sure of one thing: they would be going to war.

As the authorities interrogated the assassins, the culpability of Serbian nationalists became apparent. Austro-Hungarian authorities were eager for a war with Serbia, but why?

Due to the rise of Serbian influence in the region following the First and Second Balkan Wars, the Austro-Hungarians feared what a powerful Serbia could do in the region.

With two great military victories under its belt, the country felt invincible and was seen as directly challenging Habsburg rule in the region.

This was seen as an existential crisis since the empire had eleven different nationalities under its rule, and they could not afford to get any bright ideas, much less material support, from a strong and independent Serbia.

But there was just one problem. Austria-Hungary could not go to war alone. This is because Russia had been backing Serbia for decades and made it very clear that an attack on Serbia would be seen as an attack on Russia, though no formal treaty existed.

Because of this, if Hapsburg armies poured into Serbia, they would be going to war with Russia and would need German support.

For Germany’s end, they were enthusiastic about the opportunity to go to war. With nationalism on the rise since the reunification of Germany and the desire to increase German power in Europe and the world, the Kaiser saw the impending war as a way to defeat all of Germany’s enemies once and for all.

The German delegation assured the Austrian one that a blank check would be written to support them financially and militarily.

With the support of Germany now secured, Austria-Hungary then decided they needed a legal reason to invade Serbia.

Over the next two weeks, the administration crafted a ten-point proposal that they assumed would be inconceivable for the Serbians to accept. When they rejected it, this would be the legal basis to invade Serbia.

As the Hapsburg government drew up the proposal, France met with Russia. These meetings confirmed that if Russia were to get into a war with Germany, the French would honor their secret 1894 military alliance that was created in the aftermath of Germany, Austro-Hungary, and Italy’s Triple Alliance.

Now, with French and Russian support for a wider war, the stakes were raised.

Once Austrian authorities delivered the ten-point proposal, the Serbian government actually accepted every point except for one that would allow Austrian investigators into Serbia to prosecute a case against Black Hand members.

This was all Hapsburg officials needed to justify declaring war on Serbia, and they promptly did so on July 28.

On July 30, the Russian army began general mobilization. Germany began general mobilization the next day. Germany tried to secure British neutrality in the conflict, but the British were steadfast in that an attack on France would mean Britain declaring war on Germany.

On August 4, the last chance for peace was dashed when German troops poured across the Belgian frontier after being denied safe passage by the Belgian government so they could attack France. World War One was now officially beginning.

Conclusion

The murder of Archduke Ferdinand and his wife Sophie on that hot summer day in Sarajevo is the match that lit the fire that eventually started the conflagration that was World War One.

However, as many historians have noted, even if Franz’s driver had not taken a wrong turn that day, the conditions were already set in Europe for a world war.

If it were not for Princip, there would have been another event sooner rather than later, which would have caused a war.

Sources

https://archive.org/details/assassinationins0000ross_g4v6/page/18/mode/2up?view=theater

https://archive.org/details/assassinationofa0000bodd/page/40/mode/2up?view=theater

https://archive.org/details/DTIC_AD1023431/page/n23/mode/2up?view=theater

Leave a comment