In the 1960s, Margaret Howe Lovatt was at the forefront of an experiment that sought to understand interspecies communication.

Fueled by curiosity, Margaret took an unconventional approach to understanding human communication with dolphins.

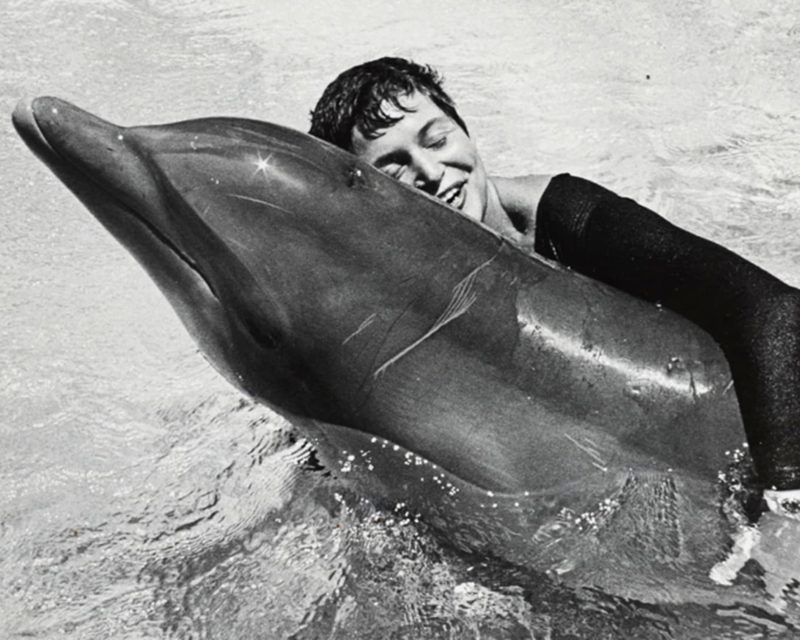

It was one bottlenose dolphin in particular that she would end up forging a deep bond with, which many have deemed unethical and controversial.

Margaret’s relationship with the dolphin named Peter was sensationalized by the press and media when the experiments on the mammals began in the 60s.

One headline even suggested that Margaret was “dating” Peter, though this is a misleading take on the story.

This isn’t just a story of scientific experiments on interspecies communication; it’s a tale of questionable ethics.

Ultimately, the remarkable story ends in heartbreak, though one question remains: why wasn’t the tragic end avoided?

The First Dolphinarium

In the early 60s, Margaret Howe Lovatt lived on the island of St. Thomas in the US Virgin Islands. It was here where her brother-in-law would tell her about a secret lab on the island that was conducting dolphin experiments.

Her intrigue got the better of her, and in 1964, Margaret made her way to the laboratory, despite having no scientific background, to learn more.

Here, she’d discover the brainchild of neuroscientist Dr. John Lilly, who had designed the lab to learn more about interspecies communication. Specifically, the purpose of these experiments was to try and teach dolphins to speak like a human.

John and his wife, Mary, had long been fascinated by large marine wildlife. They’d often take themselves on expeditions through the Caribbean to observe the mammals.

In the 50s, the couple discovered that Marine Studios in Miami was keeping a dolphin in captivity. This intrigued the pair since dolphins weren’t considered clever or interesting enough to observe. In fact, up until that point, they’d been considered the “rats of the sea.”

These days, to consider dolphins as “vermin” seems unfathomable. But, in the 50s, the fish-eating mammals were considered pests by the fishermen who saw them as competition.

With Marine Studios capturing a wild dolphin, people were now able to see the mammals were, in fact, playful, intelligent, and full of character.

The solitary dolphin at Marine Studios was even able to learn tricks, endearing the paying public who flocked to see him. Dr. John Lilly was immediately intrigued.

For the first time in history, a dolphin’s brain was studied. The captive mammal was fitted with fine probes on their head, allowing the cerebral cortex to be analyzed. John initially designed the small probes to study the brains of monkeys, but he found they worked with dolphins, too.

However, the mammals proved a more difficult subject to implant the probes into. The rhesus monkeys he’d previously studied were sedated when the probes were affixed. Dolphins are unable to be sedated since they won’t breathe while under anesthesia.

Still, Dr. John Lilly persisted in his studies and eventually created the first-ever dolphinarium, consisting of three dolphins: Sissy, Pamela, and Peter. It was here that Margaret Howe Lovatt would be introduced to Peter, and the start of a curious bond began.

The Human-Dolphin Connection

When Margaret made her way to the dolphinarium laboratory, she was met with British anthropologist Gregory Bateson, who was working there alongside Dr. John Lilly.

Gregory asked Margaret what she was doing at the lab, and she replied that she wanted to see if she could help with the dolphins. It was an unusual request that impressed Gregory, who took her to meet Sissy, Pamela, and Peter.

Margaret sat and watched the dolphins, noting their behaviors and jotting down her observations. When Gregory took a look at her notes, he was again impressed with the young woman’s desire to know more about the dolphins.

Before she left the lab that day, he told Margaret she could return whenever she wished. It would be an invite she would make use of.

Returning to the laboratory, Margaret would learn more about Dr. John Lilly’s studies. In particular, he wanted to discover if dolphins could learn and communicate in English via their blowholes.

This intrigued Margaret, who wanted to help teach the mammals how to communicate with humans, a feat that had never been attempted before. She’d spend time with the three dolphins, getting to know them and doing her best to forge a bond with them.

But something didn’t sit right with her. Every night, once the lab workers were done working, they’d all jump in their cars and leave the compound. This meant the dolphins were left alone, something that upset Margaret.

So, she suggested that she live in the building they’d dubbed “Dolphin House” so she was there around the clock. She reasoned that being there all the time meant a greater chance of a bond and, therefore, successful communication occurring.

In 1965, Margaret spoke to Dr. John Lilly and expressed her desire to plaster the walls of the building she’d be living in and fill it with water.

That way, she could spend as much time as possible with one of the mammals, cohabitating with them to forge a stronger connection. Dr. Lilly agreed, and Margaret chose Peter to join her in her living quarters.

By that summer, the room was set up to accommodate both a dolphin and an adult human, which is no easy task. The space was flooded with a few feet of water, and Margaret’s bed was on an elevated section of the room.

In order to carry out her written work, a makeshift desk was suspended from the ceiling over the water. The unique layout worked for both Margaret and Peter, who would live with each other six days a week.

On Sundays, he’d be returned to the pool that Sissy and Pamela lived in, giving the mammal and his human roommate time apart.

Some nights would be lonely for Margaret, who had fleeting thoughts of wondering why she was doing this. But, she’d see Peter’s bright eyes looking up at her and remember that nobody else on the planet was doing what she was doing – attempting to communicate with dolphins.

Peter’s English lessons always began with Margaret ensuring the young dolphin greeted his teacher with “Hello Margaret” through his blowhole. However, the “M” sound was difficult for Peter.

Still, Margaret would attest to Peter working hard to get the sound right for her. The dolphin would bubble his way through the water toward her, greeting her with the best English he could come up with.

The adolescent dolphin would get two speech lessons a day. According to Margaret, it was in between these sessions that true bonding occurred.

She told of Peter’s curiosity about her human anatomy, looking at her legs and knees for extended periods, nudging them. Margaret felt Peter was trying to figure out how her limbs worked, and his curiosity charmed her.

Eventually, after many productive lessons, something began to distract Peter away from his English classes: his natural male urges.

Margaret And Peter’s Encounters

Dr. John Lilly was insisting Margaret focus on teaching the mammal English. However, Peter was quickly becoming restless and had other things on his mind besides English lessons.

The dolphin was an adolescent, and he began having male urges that got in the way of his learning.

Initially, Margaret would move Peter into the downstairs pool so he could spend some more time with the female dolphins. But, the disruptions and upheaval of moving from room to room ate into his and Margaret’s time together.

Moving Peter several times a day wasn’t practical. So, Margaret would come up with another solution: to relieve the dolphin herself. Peter would rub on Margaret’s knees, feet, and hands to let her know his urges.

Margaret would say she was happy to relieve the mammal, but the adolescent would sometimes get rough, making her uncomfortable. Still, it was a necessary deed she carried out to ensure the dolphin was able to focus during his lessons.

Margaret would insist the act was never sexual on her part, though she has admitted it was perhaps “sensual.” She also insisted the sessions were never private, and anybody could observe the pair in the pool at any time of the day.

Still, despite her protests that the encounters were simply a requirement of the study, the media had a field day with the news of the experiment. Some would suggest she was “dating” Peter.

Most of these publications never made their way to the island of St. Thomas, where Margaret resided. The island only had two magazine stores, though, on one occasion, she did spot an article covering her and, specifically, the act of relief she gave Peter.

Margaret chose to ignore it. The media didn’t understand the purpose of her studies, so she paid them no heed.

As the study went on, though, there would be another big distraction in the form of LSD. It was the 60s, the burgeoning of the psychedelic era, and LSD was the mind-altering drug of choice. In particular, it became neuroscientist Dr. John Lilly’s drug of choice.

He used it at parties recreationally but wanted to try and involve the drug in his studies with dolphins.

The LSD Experiments

After discovering LSD, John’s views on science and the experiments he was carrying out changed. He found that the drug expanded his thoughts and believed it would encourage the dolphins to learn the English language better.

He began injecting the two female dolphins with the substance but spared Peter after Margaret voiced her concerns about him drugging the dolphins.

However, injecting the mammals was dangerous; there was no way of knowing how they would react. Different species react differently to different drugs. For example, ketamine was created as a horse tranquilizer. For humans, it’s hallucinogenic.

Since the lab didn’t belong to Margaret, she had no official say on what went on there, so she felt powerless to stop the doctor from experimenting how he wanted, ethically or otherwise. However, the results disappointed John – the dolphins didn’t react to the injections.

Meanwhile, Margaret and Peter continued to bond. What began as lessons ended in the pair simply enjoying their time together.

As autumn of 1966 came by, John’s interest had moved from trying to communicate with dolphins to indulging in LSD. As such, his regard for Peter and his welfare also dwindled.

John’s indifferent attitude toward the experiment and the dolphins soon drove away the laboratory staff, which in turn caused the funding for it to be stopped.

After six months of being together almost every day, Margaret and Peter were faced with being separated; the lab was being closed.

As much as she wanted to, Margaret couldn’t keep Peter. He wasn’t a housepet but a wild mammal with complex needs and wants.

Ultimately, Peter and the two female dolphins were shipped to Miami, where John owned a disused bank. Here, the three were kept in tiny tanks void of sunlight.

There was little Margaret could do, though she didn’t have much time to consider rescuing Peter before she got a phone call from John just two weeks after the move to Miami. “Peter’s dead,” he told her.

Tragedy Strikes

With Peter’s new surroundings being a far cry from his spacious pool in St. Thomas, he didn’t adjust well. On top of that, he’d been taken away from his constant companion, Margaret. In a matter of days, the young dolphin deteriorated.

Unable to cope with the significant changes, Peter ended his own life.

For dolphins, breathing doesn’t come automatically. For this reason, they always remain conscious, even when they are sleeping. Each breath they take is a controlled effort.

They have been known, when dealing with grief or stress, to end their own lives by refusing to breathe. When Peter couldn’t take his new environment any longer, he stopped breathing and sank to the bottom of his cramped tank.

It’s been theorized that Peter died of a broken heart.

Margaret, however, didn’t feel as strongly, saying she wasn’t “terribly upset” over his death. She reasoned that it’s better he’s gone than living a long, unhappy life in a tiny container.

After the tragic turn of events, Dr. John Lilly continued to study dolphins. Still, no one else forged the same kind of connection – or results – as Margaret and Peter. John passed away in 2001.

Margaret Howe Lovatt remains on the island of St. Thomas, eventually moving back into the Dolphin House with her husband, whom she met while working on the experiment. They had three children together.

Now in her 80s, Margaret has lived a quiet life since her involvement in the 1965 experiment, though in the decades that have passed, she hasn’t bonded with a dolphin quite like she did with Peter.

Sources

https://www.historydefined.net/margaret-howe-lovatt/

https://www.historicmysteries.com/margaret-howe-lovatt/

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jun/08/the-dolphin-who-loved-me

https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn25751-talking-dolphins-and-the-love-story-that-wasnt