“If the story of his heroism were a movie script, you would not believe it.” These words, spoken by President Ronald Reagan in 1981, are probably the best way to sum up Master Sergeant Roy Benavidez’s actions on May 2, 1968.

On that day, Benavidez carried out arguably one of the most incredible acts of bravery during the Vietnam War and in the annals of US Army history.

But who was Roy Benavidez, and what did he do in life to earn the title of the real-life Rambo?

Early Years

Roy Benavidez was born to a Mexican father and Yaqui mother in southern Texas in 1935. Within two years of his birth, his father passed away from tuberculosis, and just three years after that, his mother also succumbed to the disease.

Now an orphan, his uncle took him and his siblings in to raise as his own. But as he later recalled, life in Texas as a Hispanic person at that time was not very good.

Benavidez remembers growing up that there was rampant racism in his hometown. Frequently, Hispanic and African-American people were not allowed to eat in restaurants, move freely, and were forced to work menial jobs.

Due to the hardship of his uncle providing for six of his own children, plus his two adopted children, Benavidez was forced to drop out of school during the 7th grade to work full time.

From his teenage years until he was 17, Benavidez worked a variety of odd jobs, including ranch hands, shoe shiners, and tire changers at a Firestone tire shop.

When he turned 17, he joined the Texas National Guard to better provide for himself and his family. Realizing that he enjoyed Army life better than what his hometown could offer, he requested a transfer to active duty, which was granted in 1955.

Thus began a new chapter in Benavidez’s life.

First Tour In Vietnam

After being transferred to active duty, Benavidez longed to be part of one of America’s elite formations, the 82nd Airborne Division. And he just so happened to get his wish through a chance encounter.

One day, while assigned as a driver, Benavidez was tasked with driving the famed General Westmoreland. During the drive, the Sergeant and General struck up a cordial conversation.

Benavidez mentioned that he wanted nothing more than to be a paratrooper, even going as far as saying he would pay his own way in.

While nothing could ever be proven, within a few months of that conversation, Benavidez’s request to go airborne was approved, and he was soon earning his jump wings down at Fort Benning, Georgia.

After completing jump school, Benavidez was assigned to the famed 82nd Airborne Division. During this time, he performed quite well and earned the respect of his chain of command, who recommended him for recruiter duty.

Upon completing a recruiting tour, he found that his unit had left him. In 1965, the United States intervened in the Dominican Republic, and his buddies were all serving down there.

Instead of joining them, he found out that he had been recommended to serve as an advisor to a South Vietnamese infantry battalion. Though certainly not his first choice, he understood orders were orders, and off he went to Vietnam.

Upon arriving in Vietnam, Benavidez was struck by the difference in reality on the ground.

Instead of idyllic French villas and a struggling army who just needed a helping hand, he found that the country was in the throws of a civil war with their supposed allies not wanting to fight their friends and relatives in the Viet Cong.

Despite this, Benavidez was a soldier first and would carry out his duty to the utmost.

During his first tour in Vietnam, he was assigned to a South Vietnamese infantry battalion in the Central Highlands.

As a senior enlisted man, his role was to accompany the patrols that ventured outside the fortified bases in the area. However, he soon found that the South Vietnamese were hurting more than helping.

For example, after one particularly close call with a Viet Cong sniper, Benavidez watched a South Vietnamese platoon commander torment and murder several villagers he claimed were VC. And that was not all.

Benavidez additionally avoided death one Sunday when another South Vietnamese soldier invited him to attend Sunday Mass, a weekly ritual for him. Sensing something was wrong, his fellow advisors urged him not to go.

It ended up saving his life as the jeep of soldiers attending church that Sunday was blown up along the way with no survivors. The traitorous ARVN officer was never seen or heard from again after that.

Because he was jaded by his experiences so far leading ARVN troops into battle, Benavidez requested to lead a recon mission into enemy territory when he heard rumors a large NVA force was camping nearby.

After getting permission from the Vietnamese battalion commander, he led a patrol of ARVN troops, dressed in VC black pajamas to blend in with the locals, on a recon mission.

During this mission, he confirmed the rumors when he discovered evidence of a large NVA presence nearby. Eagerly reporting back to camp, he briefed the South Vietnamese on what he saw but was disappointed when they did nothing with such valuable intelligence.

Probably because of this, Benavidez decided to go out on his own intelligence-gathering mission. But this time, it would be different.

The facts about what happened to Benavidez remain foggy since he lost all memory of the incident. But what is known is that he was found the next day on a trail, unconscious, by a patrol of US Marines.

Though wearing black VC pajamas, he wore his dog tags that identified him as a US soldier. Having been knocked unconscious and paralyzed by an unknown force, likely a landmine, he was evacuated back to the States to face one of the greatest challenges of his life: learning to walk again.

Returning To Duty

Upon returning to the States, he was being taken care of at Fort Sam Houston Medical Center back in his home state of Texas. Though he was close to his family, he was far away from recovery.

Due to luck, circumstance, or divine Providence, when the landmine went off, it did not send any shrapnel into his body. However, there was a large X-shaped bruise on his buttocks, and he suffered severe internal damage.

As the doctors put it, his spinal cord reverberated like a whip while his brain bounced around inside his skull. However, despite not being able to walk, he suffered no brain damage or issues with his spinal cord. He just couldn’t feel anything below his waist.

Despite months of physical therapy, Benavidez was not making much progress. After several months of trying to get better, Army doctors had written him off and were getting ready to discharge him. Benavidez would have none of that.

Instead, on his own and against doctors’ orders, he began a grueling physical training regimen by himself at night. Each night, he would throw himself down from his bed and crawl to the wall. Then, he would try and prop himself up between the two night stands between his bed and the man next to him.

At first, the night nurses chastised him and put him back in bed. But after seeing him get up each night and try to stand up despite the immense pain in his back, the nurses and other patients began to encourage and cheer on Benavidez.

After weeks of this, he finally began making progress. In the beginning, he could stand just for a short period. Then, he started moving his toes, then twisting his feet, and finally walking.

After several months of this, Benavidez beat the odds, and instead of being medically discharged to spend the rest of his days in a wheelchair, he walked out on his own two feet and got orders back to the 82nd Airborne division.

Once Benavidez was back on duty, it was still a long road to recovery to get back to where he was before. While he spent his days pushing papers, he spent his early mornings and evenings running and going back to the gym.

Despite the intense pain in his back, he continued to get stronger every day until he was finally back to the physical fitness he was at before. Then, in 1967, he decided to put in an application package for the US Army Special Forces.

Known as the Green Berets, these soldiers are among the most highly trained and highly motivated soldiers in the US Army.

Their duty is to train and advise foreign militaries to allow countries to sustain their own defense without US support.

The training pipeline was and remains grueling today. Benavidez wanted to be a part of this elite unit, but there was a little snafu: He never got a waiver for his back.

Not letting that stop him, he pulled some old forms from the trash, typed the required information, forged a few officers’ signatures, and backdated it a few years. With his “waiver” in hand, he was approved to attend Green Beret training. But it would not be so easy.

Despite being a very intelligent man, having survived his childhood and a tour in Vietnam already, Benavidez struggled with the intense academic program in Green Beret training.

However, much like overcoming his back injury, he too quickly adapted to the intense academic rigor of the course beyond its back-breaking physical aspect.

Upon earning his coveted Green Beret, Benavidez thought he was going to go to South America since one of his friends that was going to Venezuela recently broke both his legs in a parachuting accident.

However, despite being a native Spanish speaker, Benavidez was not destined for South America; he was going back to Vietnam once more.

Six Hours In Hell

In January 1968, Benavidez was finally back in Vietnam. However, the war was much different now. When he was there in 1965, the war was primarily an advise and support role for the American military.

Now, the full might of the US armed forces was being brought to bear in toe-to-toe fights with Communist forces. Because of this, the mission was slightly different this time.

Before, where advisors had needed to vet missions and operations through the Vietnamese chain of command, Benavidez and his team were there to train irregular forces in the art of jungle warfare.

Due to the unreliability and threat of spies endemic throughout large portions of the South Vietnamese military, the Green Berets decided to partner with minority groups who were seen as more trustworthy and reliable to help carry out some of the most dangerous missions of the war.

To this end, the Green Berets began working with Montagnard, an umbrella term for indigenous peoples much like “Native American” is in the US. For the most part, these groups were ardent anti-communists and eager to receive training and guidance from US Army trainers.

Over the next several months, Benavidez continued training and leading groups of Montagnard known as the Civilian Irregular Defense Group or CIDG, on patrols deep into enemy territory. That is where the events of May 2, 1968, come into play.

On that day, there were supposed to be two CIDG teams led by three Green Berets. Their mission was to insert west of Loc Ninh, northwest of Saigon, and along the Cambodian border, and attempt to gather visual intelligence on supposed large concentrations of NVA troops in the area.

Though the Green Berets and their CIDG counterparts were well-trained and well-equipped, it was a dangerous mission.

This part of Vietnam was near one of the main arteries of the infamous Ho Chi Minh trail. As such, large concentrations of Communist troops and equipment could be expected, as well as little support from friendly ground forces.

Their only hope if they got into trouble would be extraction via helicopter. But even though the mission was risky, it needed to go on.

As luck would have it, Benavidez was not slated to go on this mission. Instead, he was fast asleep in his bunk, catching up on rest after several arduous days of training with new CIDG recruits. Sleeping this one off, the two teams left at first light towards their objective near the Cambodian border.

After getting dropped off, the joint America-Vietnamese recon team went off. However, less than an hour later, disaster struck. As the team cut their way through the dense foliage, they ran into an NVA wood-cutting party that was similarly hacking their way through the jungle.

In a sudden hand-to-hand melee, the team killed the three communist soldiers with their knives, but not before one of them let loose a burst from his AK-47.

Stunned, the team decided to backtrack and ask for an extraction. Higher headquarters in the command chopper above refused and ordered the team to continue the mission.

However, as the team was doubling back to go a different way, they stumbled onto another NVA patrol.

Not knowing what to do, the shocked and surprised Americans were only saved at that moment by a quick-thinking CIDG man who claimed he was an officer and was leading his patrol to locate a downed American helicopter.

At first, the ruse seemed to work until the South Vietnamese operator turned around and screamed in English, “They know!” The fight was now on.

Though the group quickly eliminated all twelve of the NVA soldiers, their cover was now fully blown. After getting permission for an immediate extraction, the team members began running back toward the landing zone. But fate would not again be in their favor.

No matter how many NVA the team killed, more and more seemed to be swarming out of the jungle. Some of the CIDG operators claimed they heard tracked vehicles, and NVA troops began setting up numerous heavy machine gun positions.

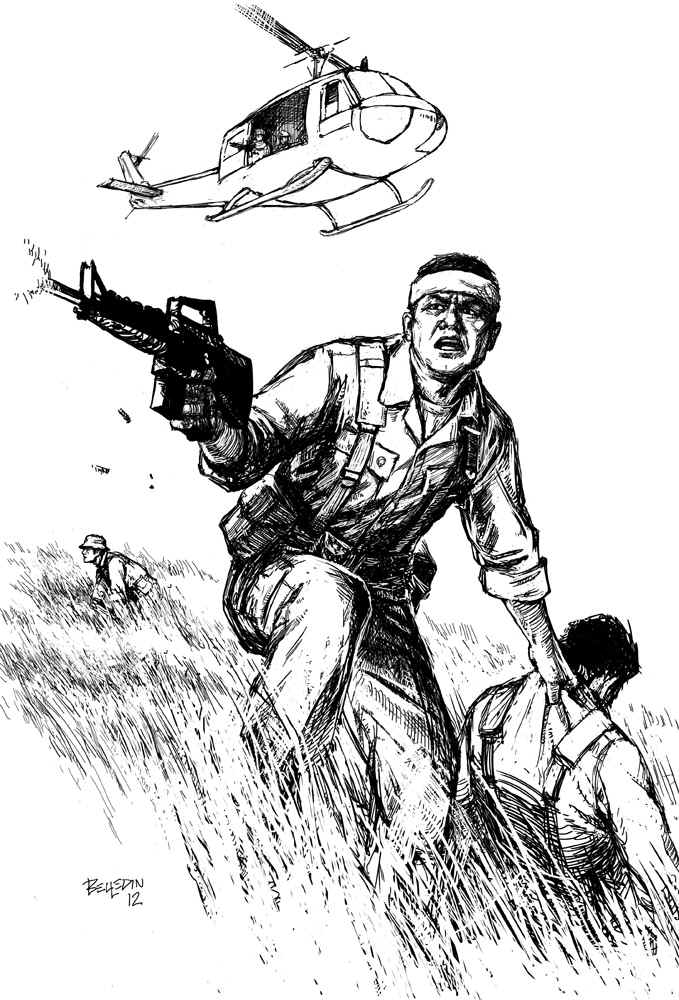

As they fought their way back to the landing zone, enemy fire began taking out the team. Numerous CIDG operators were shot dead, and two of the three Americans were killed. With just a handful of men left alive and several aborted rescue attempts, time was running out. That is when Benavidez decided to act.

Back at their base camp, Benavidez slept in like he originally planned but was startled by all the commotion. Everyone around the camp seemed to be sitting around a radio, listening to the action unfold. After a few minutes of listening to his teammates’ dire situation, he knew he had to act.

As two helicopter gunships returned, Benavidez instinctively hopped into one of them. Though he was armed with his bowie knife and a burning desire to save his comrades, he knew he was their only hope.

As the gunship he was riding in got closer, he could tell just how murderous the fire was. It seemed like the gunships were flying through a literal wall of bullets, and he would be killed before he even got there.

Miraculously, Benavidez made it to the landing zone and rolled into the melee with nothing more than his knife and a medical bag.

Before he could even make it to his team, he received his first wound, a gunshot to the thigh. After making it there, he took in their sorry state and realized they were in trouble.

Everyone who was still alive was wounded. Their defensive perimeter consisted of nothing more than a few trees and tall grass. With the enemy closing in, he knew he had to quickly get everyone out of there.

But as the latest helicopter came in to save them, disaster struck. A lucky NVA shot and killed the pilot. Lifeless at the controls, the bird took a nose dive into the ground. Now, with their ride no more, Benavidez then led an effort to rescue the surviving crew members.

After freeing the co-pilot and one door gunner who had survived, the hodgepodge team of walking dead soldiers created another defensive perimeter, this time out of the bodies of dead NVA soldiers.

As the enemy closed in around them, their primary defense was calling in barrages of airstrikes and helicopter gunship support.

As the afternoon wore on, their situation became worse. Benavidez continued to receive wound after wound, from shrapnel wounds from enemy mortars and grenades to more bullet wounds over different parts of his body.

In fact, at one point, he was bleeding so much from his face that he could not even see the radio handset to call in more airstrikes.

As the battle continued, their position deteriorated more rapidly. After one last close barrage of airstrikes where the jets were flying so low they could feel their engine heat, the enemy was clearly regrouping for one final push. That is when their saving grace arrived.

One final helicopter attempted to land and made it. Benavidez encouraged the survivors to run for their lives while he covered them.

Picking up one of his teammates who was badly wounded, he made his way to the helo when, all of a sudden, he was struck from behind. A sneaking NVA soldier hit him in the back of the head with his AK-47.

Benavidez turned around in enough time to be hit again in the jaw.

As he lay on the ground, the NVA soldier tried to jab him in the stomach with his bayonet. Instinctively grabbing the knife, Benavidez mustered all his strength to stand up and stab the soldier in the chest while his bayonet was lodged in his left arm.

With his attacker dispatched, Benavidez finally made it to the helicopter, pulled in all the wounded who could not get in themselves, and made their way back to base.

On the way back, Benavidez could finally take stock of how bad of shape he was in. Covered in several dozen bullet, bayonet, and shrapnel wounds, he was, in his own words, swimming in his own blood.

As the gunship closed with their base, the onboard medic wrote him off as a soon-to-be KIA and did not treat his wounds.

After landing, the Americans began pulling the dead and wounded off the gunship. In Benavidez’s confusion, he accidentally threw two dead NVA soldiers onto the helo as they made their escape.

Thinking he was also a dead NVA due to his oriental complexion, they began zipping a body bag around his feet.

Sensing that he would soon suffocate if put into the bag, he mustered all his strength for one last defiant act: spit in the face of the medical officer who was about to declare him dead.

Once those on the ground realized he was alive, Benavidez was rushed to Saigon and, from there, to the United States to recover from his wounds.

Conclusion

In the months and years following the action that day, it was clear to everyone that Benavidez was a hero who saved at least 11 American and Vietnamese lives that day.

However, due to the fact that there was no surviving American witness to the action, as required by regulations, the Army instead awarded Benavidez the next highest award, the Distinguished Service Cross.

Not happy with this outcome, numerous Army officers led a campaign to find a living witness to present testimony to award the Medal of Honor.

After several years of searching, they located the only surviving teammate of his from that day, who Benavidez thought had been killed.

Upon submitting his ten-page report on the action, Benavidez was immediately approved for the Medal of Honor. On a cold winter day in February 1981, President Ronald Raegan awarded him the long overdue honor.

Sources

https://archive.org/details/threewarsofroybe0000bena_y2c6/page/118/mode/2up?view=theater

Leave a comment