For many of us, when we take a flight, bothersome thoughts often linger in the back of our minds.

What if we crash? What if the plane malfunctions? What if there are people on this plane who have dangerous intentions—what if there are hijackers among us?

For the passengers of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 961, they faced the horrors of the latter scenario and found themselves 39,000 feet in the air as three men held the plane captive.

The three young men waited until shortly after the aircraft had taken off before storming into the cockpit and demanding the plane be diverted to Australia instead of its planned destination of Nairobi.

They had a bomb, they said, and it would be detonated if the pilots and passengers didn’t comply with their demands.

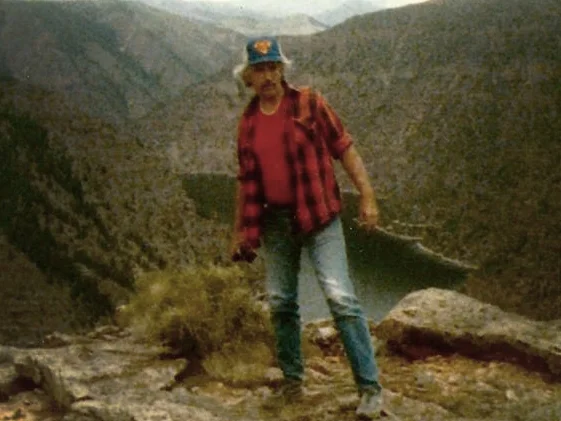

Captain Leul Abate was a veteran flyer and was resourceful in his attempts to outsmart the hijackers, who, for all their boldness, had very little knowledge of airplanes.

The pilots and passengers alike did what they could to pacify the three men, though after a while, things took a turn for the worse: the plane ran out of fuel.

Subsequently, the plane hurtled toward the Indian Ocean at over 200 miles per hour.

The ensuing collision was brutal, and nobody should have survived. By some miracle, some passengers did, and this is how we’ve come to know the full, terrifying story of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 961.

From Routine Flight To A Horrifying Hijacking

On November 23, 1996, Ethiopian Airlines Flight 961 departed Bole International Airport in Addis Ababa, heading toward Nairobi, Kenya.

The aircraft had 163 passengers and 12 crew aboard. Some were tourists heading to the capital, others were businessmen traveling for work, and some were visiting family.

Captain Leul Abate was an experienced pilot, and co-pilot Yonas Mekuria had thousands of flying hours under his belt. Between them, you couldn’t have hoped for a more robust and knowledgeable team at the helm of the aircraft.

The flight began as any other commercial flight. Weather-wise, it was a perfect day for a flight, and the passengers aboard settled in as the plane took off.

Many of them had done this flight multiple times before, and the straightforward journey was just over two hours long.

The calm wouldn’t last long, however.

Three men unbuckled themselves from their seats and swarmed the cockpit, using an ax and fire extinguisher to threaten and coerce the crew and passengers into doing as they were told.

They warned the terrified passengers that they had an explosive and would detonate it if their demands weren’t heeded.

There was no denying just how serious the three men were, and witness accounts have later testified that they truly believed the hijackers didn’t care if they died or not.

The hijackers wanted just one thing, aside from total compliance: the plane to be diverted to Australia.

Alemayehu Bekeli Belayneh, Mathias Solomon Belay, and Sultan Ali Hussein wanted to flee Ethiopia and seek asylum in Australia, and this was their misguided way of doing so.

Tired of their homeland’s political and economic situation, they were led to believe life down under would be full of luxury and comfort.

The hijackers’ lack of aviation knowledge or understanding of how planes work didn’t stop them from enacting their plan to get there.

The Boeing 767 they’d taken over simply didn’t have enough fuel to get to their desired destination; after all, it was only supposed to be flying 719 miles to Nairobi.

Australia was over 7800 miles away. The fuel won’t get them there, and the tank of the 767 didn’t have the capacity to get them that far, either.

If they were to travel that distance, Captain Leul Abate tried to reason with the men that he’d need to stop and refuel. The hijackers wouldn’t listen. They wanted their demands met, or they’d blow up everyone on the plane, including themselves.

The men said there were eleven of them on the plane, and nobody knew who among them was friend or foe.

There was no doubt among terrified passengers that the men meant every word.

How were they to know that there was no bomb? And that, in reality, there were only three hijackers?

The Hijacker’s Impossible Demands

Fuel—and time—was running out.

To keep calm on the plane, the pilots tried to assure passengers they still had some control. In fact, Captain Leul was covertly communicating with air traffic control, who in turn alerted authorities of the hijacking.

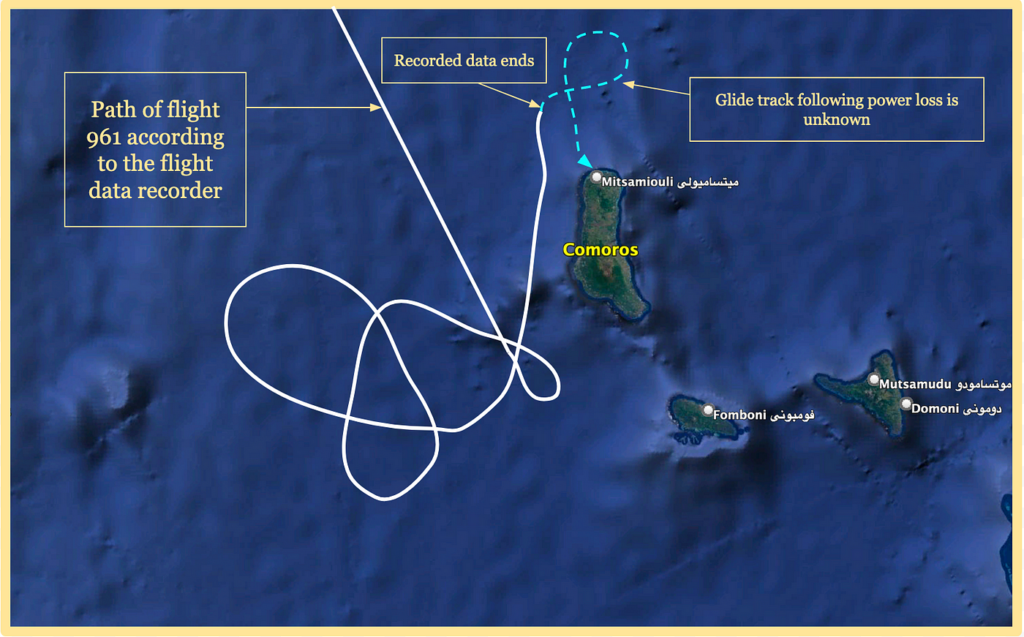

Captain Leul defied the hijackers’ demands to head to Australia, instead following the African coastline south. Since the three hijackers knew little about aviation, they couldn’t have known they weren’t heading in the direction they wanted.

However, they did notice that the land was still visible and ordered the captain to redirect and go eastward.

Still, the captain had other ideas. He was heading for the Comoro Islands.

At all times, he had a hijacker in the cockpit with him, and the other two paced the cabin.

Reportedly, the men didn’t take the situation seriously, drinking whiskey and fiddling with the aircraft’s controls, pulling levers at random with no clue as to what they controlled.

It appeared to the captain that the men perhaps didn’t want to get to Australia and did indeed want to crash.

By now, it had been a few hours since the men had taken over the plane, and the fuel was just about depleted. Captain Leul again warned them that the tank was out, and they were going to crash if he didn’t reroute to the Comoros airport.

The right engine lost its flame entirely, causing the captain to reiterate that a crash would have been imminent if he hadn’t intervened.

The hijackers left the cockpit to confer on their next movements, during which time Captain Leul used this window to speak to the panicked passengers via the aircraft speakers.

“Ladies and gentlemen, this is your pilot. We are expecting a crash landing, and that is all I have to say.”

When the hijackers heard the captain’s voice on the speakers, they charged back into the cockpit and swiped the microphone from his hands. The hijackers had no plan; that much was clear, but they certainly weren’t going to allow the captain to land at the airport.

Then, the second engine lost its flame. The plane was now merely gliding. One of the hijackers said to the captain, “Descend it—increase the speed further.”

The captain tried to reason with the hijackers that it made no difference if he sped up or not; their fate remained the same: he and everyone else on the plane were going to die in the upcoming crash.

The Crash

Eventually, the captain tried to guide the plane to the airport as best he could, but an altercation with the hijackers caused him to lose his sense of navigation, and the only option that remained was to crash land in the water.

Despite the stressful environment, Captain Leul still thought logically. He did his best to land the plane so it aligned with the waves, not against them. This would ensure a smoother landing.

By this point, many of the passengers had prematurely inflated their life jackets to brace for impact.

When the plane hit the water, it did so at an angle. The left engine and wing struck the water, and the plane also hit a coral reef.

Since the plane didn’t land as smoothly as anticipated and crashed into the water unevenly, it began to break apart. The broken sections of the plane sank almost immediately.

For the passengers who had already inflated their life jackets, they found themselves trapped in the cabin and sunk with the wreckage.

Tourists and residents witnessed the crash, and a woman holidaying on Grande Comore island recorded its aftermath. This meant help was summoned quickly after the collision.

Of the 175 people on board, three of whom were the hijackers, 125 died. Fifty people survived, though not without serious injuries.

Their survival, which was highly unlikely considering the speed and way in which they crashed into the water, was in part credited to Captain Leul’s skill, as well as the speedy rescue efforts from locals who used their boats to collect survivors.

None of the hijackers survived the crash.

Captain Leul and his co-pilot Yonas Mekuria both survived. For his actions that day, the brave captain was awarded the “Professionalism in Flight Safety Award” from the Flight Safety Foundation.

A memorial service for those who lost their lives was held in Galawa in November 1996.

Despite the terrors they faced on that fateful day, Leul and Yonas continued to fly for Ethiopian Airlines.

Sources

https://asn.flightsafety.org/wikibase/324329

https://adst.org/2014/10/ethiopian-flight-961-the-worst-hijacking-in-history-before-911/

Leave a comment