Lobotomies are an outdated form of psychiatric treatment that was intended to cure myriad mental ailments. Doctors would physically alter the brain, changing the way that people could process their thoughts and emotions.

While some patients benefitted from the procedure, many were left in a diminished mental state, and lobotomies were discontinued globally.

Treating Mental Illness As A Physical Disease

Towards the end of the 19th century, psychiatry was just beginning as a field of science, and psychiatrists were beginning to formulate theories about mental illness to try and understand human behavior.

One of the earliest theories was that mental illnesses manifested physically and that different functions were limited to specific areas of the brain. Psychiatrists began to posit that altering the brain itself could alter a person’s mental state.

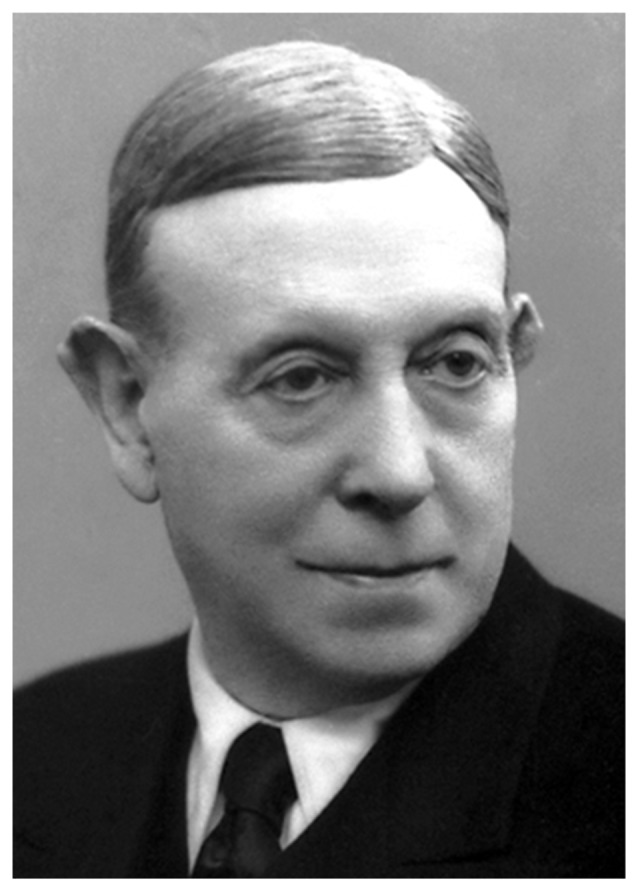

Early psychosurgeries, or surgeries of the brain, began as early as the 1880s when Swiss psychiatrist Gottlieb Burckhardt conducted experiments on psychiatric patients.

Burckhardt believed that by physically altering the brain, he would be able to ease the symptoms of, although not cure, mental illness.

Of the six patients he operated on to test his theories, only one improved; of the other five, two remained the same, two became quieter, and one suffered from seizures and died.

He grouped the quieter ones into his success rate when writing about the experiment but was eviscerated by the medical community for the dubious human experiment and conducted no further tests.

But over the next forty years, Burckhardt’s theories would slowly be revisited and reconsidered as potentially viable for the treatment of mental illness.

Treating The Physical Brain

The next major strides in the practice of lobotomies came from research conducted at Yale University by John Fulton and Carlyle Jacobsen. The pair were intrigued by the frontal lobe of the brain and attempted to understand how it connected to the nervous system.

They experimented on two chimpanzees, named Lucy and Becky, removing their frontal lobe to determine what effect it would have.

While removing the frontal lobe hindered certain motor functions and hurt the chimps’ short-term memory, the scientists were more intrigued with the changes in behavior the chimps demonstrated.

Prior to the surgery, both chimps had demonstrated an emotional response to not being rewarded when they failed puzzles, throwing a tantrum like a small child to show they were upset.

Once their frontal lobes were removed, these tantrums ceased. In fact, the chimps became so passive and apathetic that Jacobsen described the chimps as having joined a “happiness cult.”

Developing The First Lobotomy

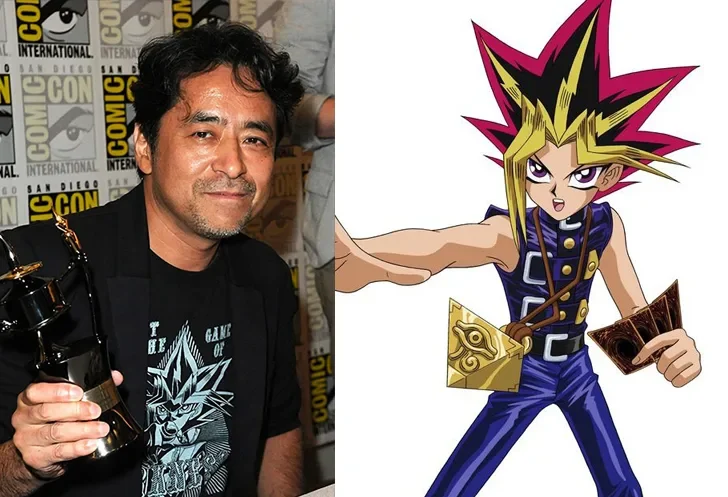

The success of these experiments inspired Portuguese scientist António Egas Moniz to translate the practice into humans. He developed a tool called a leucotome, which was a long steel rod used to sever the connection between the frontal lobes through a hole drilled in the side of the skull.

The process of separating the frontal lobe from the other gray matter of the brain utilizing this tool was called a leucotomy.

Of his first round of twenty leucotomy patients who suffered from schizophrenia, Moniz reported seven cures, seven improvements, and six unchanged patients.

As a result of the surgery, patients demonstrated similar behavioral changes as Fulton and Jacobsen found in the chimpanzees.

The debilitating effects of the mental illness faded away, and Moniz deemed any deterioration of personality was worth the lessened symptoms of schizophrenia. Moniz received a Nobel Prize in 1949 for his contribution to the field of physiology.

Moniz’s procedure was deemed a success and adopted over the course of the 1930s by the broader medical community, which was increasingly convinced mental illness manifested itself physically.

It inspired American neurologist Walter Freeman, who, after meeting Moniz at a conference in 1935, turned his attention to physically altering the brain to resolve mental illness.

After familiarizing himself with Moniz’s work, Freeman determined that it was not entirely accurate but did offer a viable alternative to searching for diseased brain tissue.

Pairing with neurosurgeon James Watts, Freeman developed a new method of physically altering the prefrontal cortex of the brain that was more precise than Moniz’s and, therefore, more effective.

Becoming Experts At Severing The Prefrontal Cortex

The new process was renamed “The Freeman–Watts prefrontal lobotomy,” and although it still required drilling into the skull, it had a smaller margin of error when inserting tools into the brain matter.

Freeman and Watts performed twenty surgeries in two months to test their new method, and when they were successful, they performed another 180 over the next six years.

When reflecting on their successes, the pair asserted that 63% of their patients showed improvements after their surgery, 24% continued to suffer from their illness, while just 14% saw their condition worsen.

One of the first patients that Freeman performed the surgery on was Rosemary Kennedy, John F. Kennedy’s sister. At age 22, she began to exhibit violent mood swings and seizures, which the family hoped to rectify with a lobotomy.

After the surgery, Rosemary was a shadow of her previous self. She had reverted to the mental state of a two-year-old, unable to take care of herself, go to the bathroom effectively, or communicate at all.

In order to protect the family’s legacy and political aspirations, the Kennedy family fully removed Rosemary from their lives.

For over twenty years, she lived in a cottage on the grounds of a psychiatric hospital that the family paid for, completely abandoned by the family that had forced her into a catatonic state.

The Search For A Better Lobotomy

After a decade of attending to surgeries, Freeman realized that the procedure required specific and expensive tools, a large staff of surgeons, and a sophisticated surgery room.

Despite the practice becoming increasingly common, lobotomies remained a largely inaccessible form of treatment, and Freeman sought a way to make the barrier to access lower for those who would most likely require the surgery: the mentally ill.

This demographic was more often than not restricted to psychiatric wards that did not have the extensive resources required for neurosurgery, and Freeman sought a way to make the procedure simpler and cheaper so that it could be done in these facilities.

He began to experiment to achieve his newfound goal. Utilizing an ice pick and grapefruit as an example, Freeman posited the transorbital method of lobotomy.

Rather than drilling into the skull to slice the connections between the prefrontal cortex and the rest of the brain, Freeman utilized patients’ eye sockets to access the inside of the skull.

By pulling down the eyelid and hammering a thin surgical instrument through the thin bone in the orbital socket, a doctor could access the brain in a less invasive manner. The tool could be navigated with ease to sever portions of the brain, leaving less damage than a leucotomy.

Transorbital lobotomies were a far simpler procedure, able to be conducted by anyone who was shown the method.

Watts was disgusted with the method, believing that Freeman had deviated from their shared interest in science in favor of developing a simple “office procedure.” In 1947, a year after Freeman conducted the first transorbital procedure, Watts ended their partnership formally.

When Was The Last Lobotomy Performed?

But the men’s techniques had become immensely popular already: by 1944, almost 700 lobotomies had been performed. In 1949, the peak year for lobotomy procedures, over 5000 people were lobotomized, and by 1951, over 18600 people had had the procedure completed.

A lot of the earliest procedures were conducted on patients with schizophrenia, but as lobotomies became more common, the pool of conditions lobotomies were used to “cure” widened.

Repeated criminal activity, hysteria, misbehaving children, and homosexuality were all conditions that led to over 60,000 lobotomies performed worldwide from the 1940s until the 1980s, although by the early 1970s, most lobotomies had ended due to growing moral opposition.

In 1977, perhaps as a residual effect of the previous decade’s activist spirit, the United States began considering how medical practices could biased toward certain classes of people.

The National Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research determined that lobotomies were being disproportionately conducted on racial minorities and that rather than providing assistance to the patients, many times, it was conducted as a method of control.

Although the procedure was framed as relieving mental illness, oftentimes lobotomies were conducted unnecessarily because the lowered cognitive state of the patients was left in was useful in exercising control.

Lobotomies may have been widely accepted as viable for a time, but the practice was always dubious.

Studies never approached a rate of near-perfect results like are required from medical practices now, and due to the nature of the procedure, there was very little feedback from the patients who lived through a lobotomy.

Since other medical practices have arisen to treat mental illness, it is for the best that the tools used to physically separate spheres of the brain have been put aside.

Sources

https://tidsskriftet.no/en/2022/12/essay/lessons-be-learnt-history-lobotomy

https://psychcentral.com/blog/the-surprising-history-of-the-lobotomy#legality

Leave a comment