In the 17th century, warship design was changing. All contemporary warships were wooden sailing vessels armed with several cannons on a gun deck. The more cannons a ship had, the more effective it was in combat.

Then, an enterprising naval architect had the idea of adding a second gun deck above the first, allowing a warship to carry twice as many cannons. While that certainly added firepower, it also added weight.

Cannons are heavy, and placing two decks of these weapons above the waterline could make a ship’s centre of gravity dangerously high.

On August 10th 1628, the Swedish Navy proudly launched its first warship to feature 64 cannons on two gun decks: the Vasa. The weather was perfect, and, watched by a huge crowd, the new ship sailed out into Stockholm harbour.

Less than 20 minutes later, and after covering a total distance of just under two kilometres, the ship was struck by a light gust of wind. The Vasa immediately rolled over and sank, taking 30 members of its crew to the bottom of the sea.

This is the story of the ill-fated Vasa. But surprisingly, that story didn’t end in 1628…

The Design

The Thirty Years’ War raged in central Europe from 1618 to 1648. It was one of the most bloody and destructive European wars ever and would leave an estimated 8 million combatants and civilians dead.

The root cause of the war was an internal struggle between Protestants and Catholics within the Holy Roman Empire, but it also drew in other European and Scandinavian nations.

Gustavus Adolphus became king of Sweden just as this war was beginning, in 1611. He was determined that Sweden would take its place amongst the great European nations.

He modernised and re-equipped the Swedish army and planned to make the Swedish Navy a formidable force.

In January 1625, an order was placed with the main shipbuilding company in Stockholm, Hendrik and Arend Hybertsson, to build four warships for the Swedish Navy. Two of these were to be ships of the line, the largest warships in use at the time.

In September 1625, a flotilla of the Swedish Navy was caught in a terrible storm that destroyed ten of its ships.

Suddenly, the new building programme became more urgent, and the king ordered that the new warships be completed as quickly as possible.

The king also began to interfere directly in the design of the new ships.

The specifications of the larger vessels evolved until they became over 200 feet long and were designed to carry 64 cannons on two decks, making them the largest and most powerful warships in the Baltic at the time.

It’s hard to imagine in these days of computer-aided design, but shipbuilding in the 17th century was largely a matter of experience and, where necessary, guesswork.

In most cases, ships were designed using existing and successful specifications.

But very few warships with two gun decks had been built anywhere in the world, and as the proposed new ships grew larger and larger, the shipbuilders simply scaled up existing plans.

This was probably understandable, but it meant that nobody had any clear idea of how the new ships would actually behave in the water.

Further interference by the king added to the problems of the new ships. He decided that the first was to be not just one of the largest and most powerful ships in the world but also one of the most lavishly appointed.

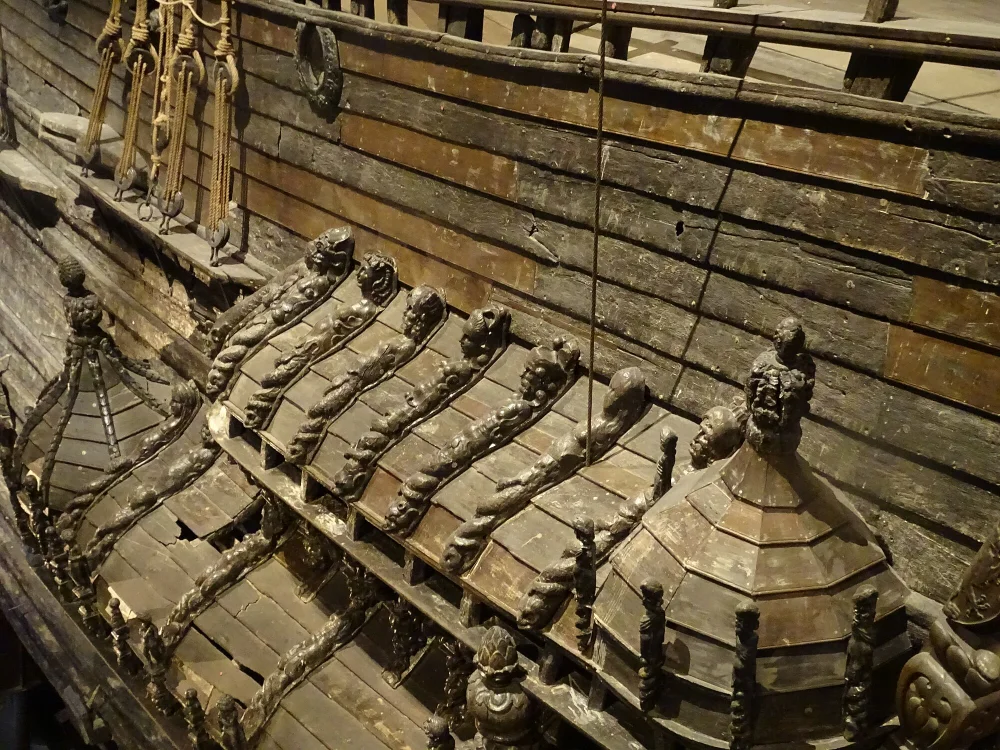

On the upper decks, hundreds of gilded carvings were added, depicting Biblical and mythological stories as well as scenes from Swedish history. These had the unfortunate effect of making the upper decks even heavier…

The Launch

After completion, but before launch, the first of the new ships, the Vasa, was moored in Stockholm harbour. Even before it sailed, people were beginning to express doubts about its stability.

An experienced naval commander, Söfring Hansson, was appointed captain of the new vessel, and he quickly instituted a “lurch” test, a standard method of assessing the stability of a ship.

A party of thirty men were gathered on the upper deck and ordered to sprint from side to side. After three crossings of the deck, they were ordered to stop – the ship was rolling so alarmingly it was feared that it might heel over.

Nevertheless, the king wanted the Vasa launched as quickly as possible. Swedish involvement in the Thirty Years’ War seemed inevitable, and the new warship would provide a much-needed boost to Swedish naval power in the Baltic.

Hundreds of people gathered on shore and in small boats to watch the launch of the mighty new warship. In the late afternoon of 10th August, the Vasa finally cast off its moorings for the first time.

There was virtually no wind, and the ship was dragged out into Stockholm Harbour, where it began to drift in the current. Then, a light gust of wind caught the sails, and the ship heeled alarmingly before slowly recovering.

The gunports were open in preparation for firing a broadside in salute to the watching crowd when a second light gust of wind hit the ship. It heeled over so far that the open gunports were submerged.

Water poured in, and Vasa sank in moments in around 100 feet of water, watched by horrified spectators.

Around 30 members of the crew died when Vasa sank, including the ship’s second captain, Hans Jonsson. The remainder of the crew and Captain Söfring Hansson survived by swimming to shore or were rescued by small boats.

Hansson was arrested and imprisoned almost as soon as he came ashore, accused of responsibility for the disaster. However, a commission formed on the king’s orders found nobody directly to blame.

The Remarkable Rediscovery

In the late 1600s, a few cannon were recovered from the sunken Vasa using primitive diving bells, but after that time, even the precise location of the wreck became uncertain.

In the 1950s, a Swedish naval engineer and amateur marine archaeologist, Anders Franzén, began searching for the Vasa. He used grapples to try to find the wreck, searching on the south side of the main shipping channel, where the wreck was thought to lie. He found nothing.

Franzén then went back to the archives to read original accounts of the disaster, and he came to a surprising conclusion: he believed that the wreck lay in a completely different location, to the north of the main channel, near the island of Beckholmen.

During the summer of 1956, Franzén used a small ship to scour this area, dropping a device that took core samples from the bottom. On 25th August, a core sample showed old black oak, the material used in the construction of the Vasa.

The survey ship moved 20 metres further on and took another sample. This, too, contained oak.

Based on these findings, the Swedish Navy persuaded a dive team to take a look. Experienced salvage diver Per Edvin Fälting investigated the bottom where the samples had been recovered.

He found what appeared to be a tall, wooden wall pierced by a number of square openings. The Vasa had been discovered.

Recovery

After more than 300 years underwater, nobody had expected that there would be much left of a wooden ship, but Fälting’s report suggested that the wreck was surprisingly intact.

Anders Franzén began building a coalition of groups that might be willing to help recover the wreck, aided by interest from King Gustavus Adolphus VI, a direct descendant of the man who had commissioned the Vasa and a trained archaeologist.

The Swedish Navy agreed to provide divers and support vessels. The Neptune Diving and Salvage Company, a division of Broströms, Sweden’s largest marine salvage company, agreed to provide equipment and resources free of charge.

For over two years, divers toiled to excavate a series of tunnels beneath the wreck. These were used to construct a giant basket that surrounded the hull.

In August 1959, the ship was lifted for the first time, not to the surface, but so that it could be moved to shallower water closer to shore where divers could work on it more easily.

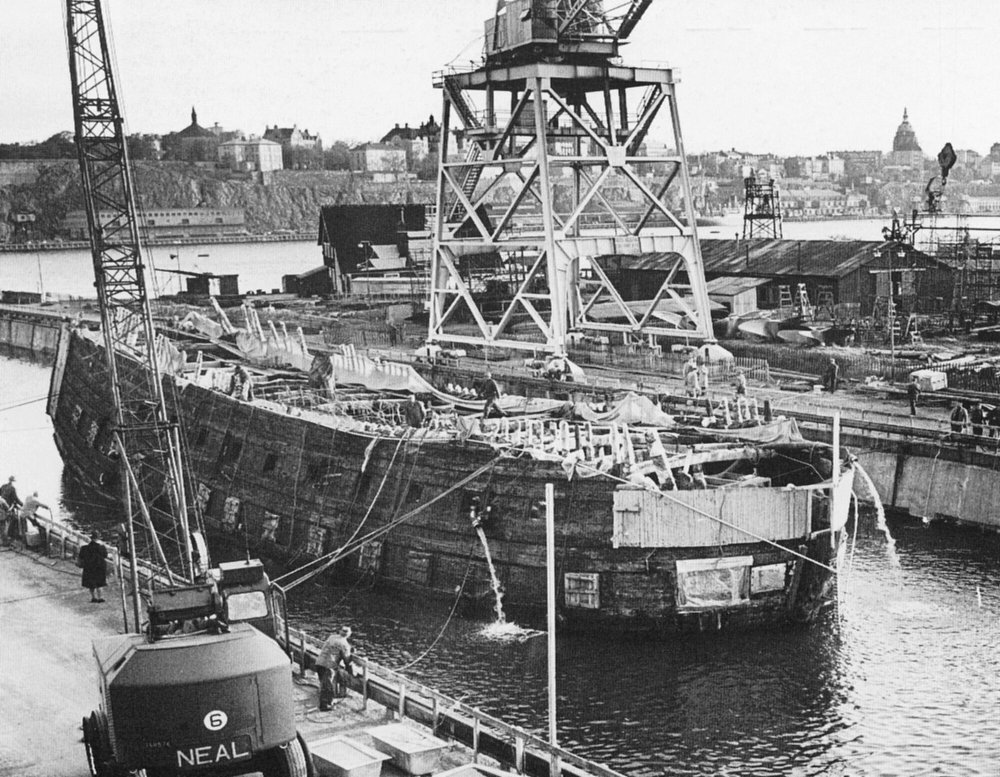

For 18 months, they plugged holes in the hull, covered the open gun ports, and added steel bars to reinforce the hull. Then, on 24th April 1961, the ship was finally brought to the surface.

Thousands of people crowded the shore at Kastellholmsviken when, at just after 09:00, the Vasa rose above the surface of the ocean for the first time in over 330 years.

Conclusion

The recovery of the Vasa in 1961 was only the first step in a long and painstaking process of restoration and preservation. The most striking aspect of the wreck was just how well it had survived its long immersion.

Later, it was discovered that high salinity in the waters of Stockholm Harbour had acted as a preservative.

The main structure of the ship, and even its intricate carvings, were intact, and archaeologists found thousands of period artifacts, as well as human remains, on the ship.

The Vasa provided a fascinating snapshot of seafaring life in the 17th century, as well as a detailed look at a misguided piece of naval architecture.

Modern analysis proves that the Vasa was simply too top-heavy to survive even the lightest of winds, and it was doomed as soon as it left its moorings.

In 1990, King Carl XVI Gustaf opened the Vasa Museum in Stockholm, where the Vasa and many of the artifacts recovered from the ship were placed on permanent display.

Since then, millions of visitors worldwide have come to see the only 17th-century warship that has ever been salvaged intact, the mighty but ill-fated Vasa.

Sources

https://www.vasamuseet.se/en/explore/vasa-history/disaster

https://www.vasamuseet.se/en/explore/vasa-history/search-for-vasa

Leave a comment