On 12 May 2000, Dr Rodney Marks collapsed in agony at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. As the hours passed, his condition worsened until, by that afternoon, his heart stopped.

Until flights resumed in October, no one could get in or out. With no way to investigate, rumours began to spread. Had Dr Marks simply fallen ill, or had something more sinister occurred?

Who was Dr Rodney Marks?

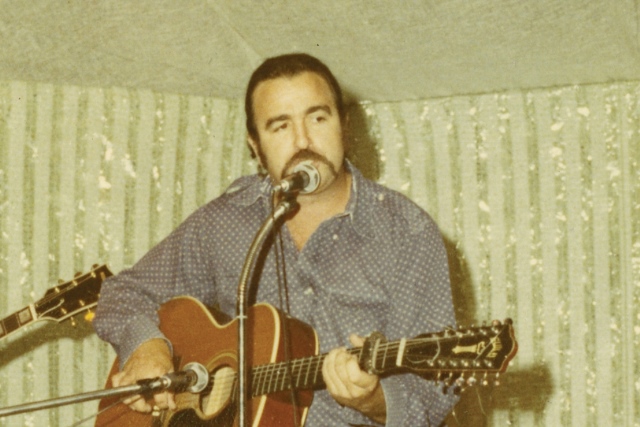

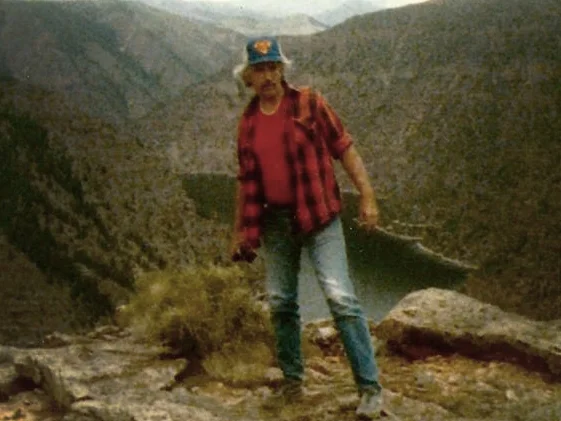

Dr Rodney Marks was an Australian, born on 13 March 1968 in Geelong, Victoria.

He attended the University of Melbourne and later earned his PhD in physics from the University of New South Wales. He had a good social life and enjoyed the occasional binge drinking session.

Marks specialised in submillimetre astronomy, studying the universe using light with wavelengths just between infrared and microwaves, which reveals cold gas, dust, and hidden star-forming regions.

His PhD research involved measuring how the air above Antarctica affects how clearly telescopes can see space – basically, how much the atmosphere makes stars look blurry. This is known as the analysis of Antarctic’ seeing’ or atmospheric turbulence.

It was a fascinating field, and he wrote multiple notes that were later turned into papers. But he never could have imagined what would happen next.

Overwintering in 1997/98

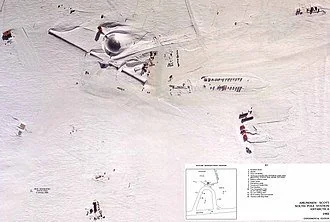

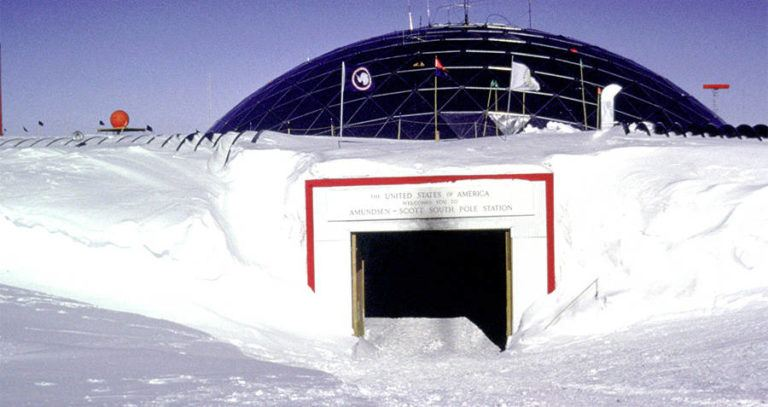

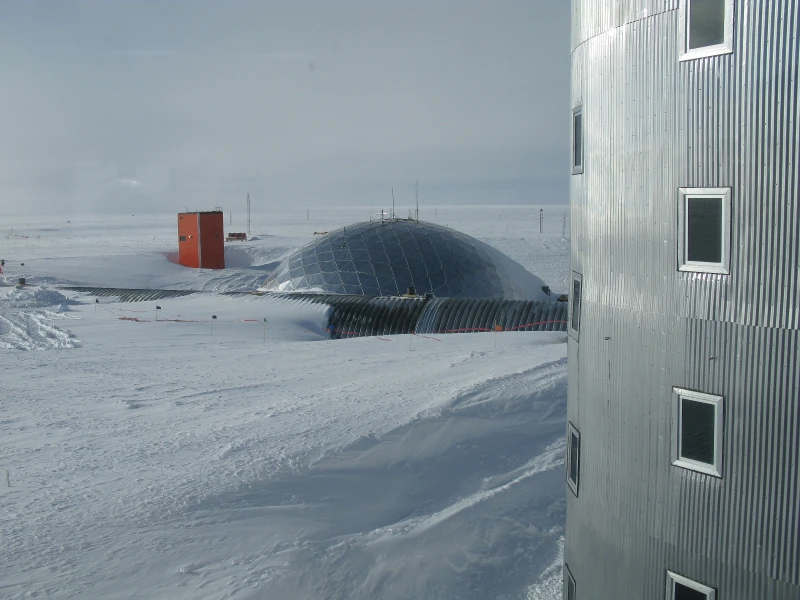

In his late twenties, Dr Marks was selected to work on the SPIREX/Abu near-infrared project, a University of Chicago-sponsored telescope project at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station in Antarctica.

Near-infrared rays make it easier to see through space dust and, thus, facilitate the study of space. At the South Pole Station, it would be his job to operate the telescope, maintain the equipment, and collect data.

As such, he packed up his things and moved to the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station, and stayed there as part of the 1997-98 ‘winterover’ season.

Winterover shifts at Amundsen–Scott typically last from around October/November until the following October/November, because once winter begins (late February or March), flights are impossible until the following summer.

Such a task is far more difficult than it might at first seem. It’s a terribly unforgiving environment and, in the depths of winter (around February to October), there’s no way of escape thanks to the extreme cold and storms. There is no way back to civilisation.

In July 1997, the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station recorded a monthly average temperature of about -66 °C (-87 °F). Also that month, the lowest daily temperature recorded was about -78 °C (-108 °F).

Winterovers – someone staying in the Antarctic throughout winter – must tolerate isolation, extreme cold, and operate complex equipment alone or with a tiny team.

Anyone operating in these conditions has to be capable of extreme focus, determination, and drive. It is a monumentally skilled and terrifyingly lonely job. But Dr Marks was up to the task. And he was ready to go back again.

How Antarctic jurisdiction and legislation works

Because Antarctica is such an isolated and extreme landmass, it’s governed in a unique way.

The Antarctic Treaty, or ATS, signed in 1959, makes the continent a zone for peaceful activity and shared scientific research, freezes territorial claims, and enforces strict environmental protection. No single country controls the land.

In practice, stations are managed by their home countries, which provide the legal and administrative framework for daily life.

However, legal authority is complicated. People are generally subject to the laws of either their home country or the country under which the station operates, which brings complications.

For example, the Amundsen-Scott Station is American-led, but situated on territory that historically belongs to New Zealand. The US doesn’t recognise New Zealand’s claim, and New Zealand doesn’t make too much fuss about it.

But even with the treaty encouraging cooperation, Antarctica remains a place where law, nationality, and logistics come crashing together, not always seamlessly. The case of Dr Marks was about to illustrate this all too clearly.

The fateful trip

After a successful stint working on the SPIREX/Abu near-infrared project in 1997/98, Marks became involved with AST/RO (Antarctic Submillimeter Telescope and Remote Observatory), a research project funded and operated by the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.

He was selected to return and winter again at the Amundsen-Scott Station, this time from November 1999 to November 2000. Like the SPIREX/Abu telescope, the AST/RO project was also based at the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station.

Instead of a near-infrared unit, though, AST/RO used submillimetre wavelengths. With a slightly more complex system, this telescope is used for studying cold molecular gas, star-forming regions, and cosmic background radiation.

All was going well. His fiancée was overwintering with him at the station. He had passed all his physical tests before returning to Antarctica, and the first few months passed as usual.

Contemporary reports describe him as the observatory’s sole operator and credit him with a very successful winter observing season. In fact, under his watch, AST/RO was on track to have “its most successful winter observing season ever”.

But then, on Friday, 12 May 2000, around a month into the inescapable polar winter, everything deteriorated. Rapidly.

Sudden poisoning

On 11 May, Dr Marks was walking back from AST/RO to the Amundsen-Scott Station with a colleague. He was suddenly feeling tired and having a significant shortage of breath. Although he had dinner with Sonja, his fiancée, his symptoms continued to worsen.

He went to bed, but at 5:30 am on 12 May woke up experiencing severe symptoms, including vomiting blood. He went to the station doctor, Dr Thompson, and would visit three times in total that day. With each visit, his symptoms were worsening, including joint pain and severe light sensitivity.

His condition deteriorated at an alarming rate, and medical staff used satellite communication to get more in-depth medical advice. But the cause of his illness remained undiagnosed.

Over the following day, his symptoms continued to get worse and worse. He told the doctor he hadn’t had a drink for two days. By the afternoon of 12 May, he was becoming increasingly distressed to the point of hyperventilating. Sonja was with him.

To help him calm down, Dr Thompson gave him an antipsychotic, Haldol, and he lay down, apparently peaceful, squeezing Sonja’s hand. But moments later, around 6:00 pm, not long after the shot, his heart stopped.

Dr Thompson hurried to perform CPR, but after 45 minutes, it became clear that Dr Marks couldn’t be resuscitated. He was declared dead at 6:45 pm.

Waiting for an accurate cause of death

The US National Science Foundation, which was in charge of the American-run Amundsen-Scott Station, issued a statement indicating that Marks had “apparently died of natural causes.” But how, specifically? That had yet to be determined.

Answers would have to wait. The Antarctic winter had arrived, so Marks’ body could not be removed from the station until flights resumed months later. It was carefully kept outside, in the deep Antarctic cold.

Eventually, the depths of the Antarctic winter passed. On 30 October 2000, Marks’ body could finally be transported to Christchurch, New Zealand, for an autopsy.

Christchurch is the main gateway city for flights to and from Antarctica, especially for the US Antarctic Program (USAP). New Zealand has long-standing agreements with the USAP to handle such cases. As such, New Zealand coroner Richard McElrea took on the case.

What the autopsy revealed

With the agreement of both the US and Australia, the autopsy and subsequent coroner’s hearings were performed in New Zealand, well over five months after Marks actually passed away. And here, the cause of death was finally determined, methanol poisoning.

Forensic pathologist Dr Martin Sage determined that Marks had ingested approximately 150 millilitres of methanol. Methanol is a type of alcohol – colourless, slightly sweet, but toxic – certainly not the kind you can drink.

A dose as low as 10 ml can cause blindness, and anything over 30 ml can be fatal for some people (tolerances can vary widely). Marks had somehow ingested five times that amount.

The complications of international investigations

The theories of foul play immediately began to emerge. After all, the remoteness of the South Pole and its isolated winter conditions made it the perfect environment to get away with ending the life of someone.

What would the investigation reveal? First, though, the investigation had to get started. And that was trickier said than done.

Per the USAP agreement, New Zealand investigators in Christchurch were in charge of the investigation. However, Dr Rodney Marks was Australian, working in an American research station in Antarctica.

Because it was US-controlled territory, the New Zealand coroner had no direct access to the scene, personnel, or full records. The investigating team would have to go through the legal and diplomatic branches to gain access to any information.

This led to endless frustration for the New Zealanders. Even though Marks was from Australia, the evidence had to come via US authorities, through the agencies they subcontracted to run the South Pole stations, all of whom were often slow or reluctant to cooperate.

For example, requests for station logs, inventory of chemicals, and other operational records had to go through intense rounds of negotiations before they were released to the New Zealand coroner.

And it must be noted that neither country – the US or New Zealand – had an immediate incentive to expedite the investigation. As such, the investigation and associated negotiations stalled.

It was 2008 – over eight years after Marks died – before the coroner reached an official verdict.

Eventually, based on all the evidence gathered, the coroner was able to bring the case to its most likely conclusion. It was decided that Dr Marks must have accidentally ingested methanol at some time one or two days before he first presented with symptoms on that fateful morning.

The cause of death was listed as ‘accidental methanol overdose’. Although many spectators around the world continued to suggest foul play, investigators uncovered no potential motives and no evidence to suggest anything of the sort.

But how could anyone accidentally ingest something so lethal? Here, we run into speculation. Authorities uncovered no clear evidence. But it’s certainly the most plausible reason for so much methanol having made it into his system.

Methanol and ethanol, the alcohol found in drinks, are remarkably similar: both are colourless and have a comparable odour, so it’s easy to confuse the two.

Marks was known to drink socially at the station, and it is possible that he unwittingly consumed methanol, mistaking it for ethanol – although, given he never told anyone at the station that he’d drunk anything, this seems improbable.

It’s also possible that the alcohol available at the station was contaminated with methanol. Production or storage errors can sometimes result in ethanol being mixed with methanol.

Methanol is commonly used in laboratories (including those at the South Pole) as a solvent. If it had been improperly stored or labelled, Marks could have accidentally consumed it. There is no concrete evidence that Marks consumed methanol directly from a laboratory source, but it remains a theoretical possibility.

Marks was eventually buried in Bellbrae Cemetery, Mount Duneed, Victoria, Australia. The exact way the methanol got into his system will likely never be known.

Sources

https://www.science.org/content/article/tragedy-strikes-south-pole-station

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2007/jan/14/antarctica.robinmckie

https://www.thepost.co.nz/nz-news/360743618/south-pole-murder-mystery-continues-after-25-years

Leave a comment