The 2013 movie American Hustle was both a commercial success and a hit with critics.

It featured a pair of likable con artists assisting the FBI in setting up an elaborate sting operation. The targets of the operation were powerful but corrupt politicians.

The crime/comedy movie grossed over $250 million worldwide and received ten Oscar nominations. To most of those who saw it, this appeared to be a piece of escapist fiction.

However, American Hustle was based on a real-life FBI anti-corruption operation.

This operation, ABSCAM, succeeded in securing the indictment of formerly respected senior politicians. But the real account was far from comedic and was widely criticized for entrapment.

This is the story of ABSCAM.

Origin

The FBI operation that became ABSCAM began in March 1978.

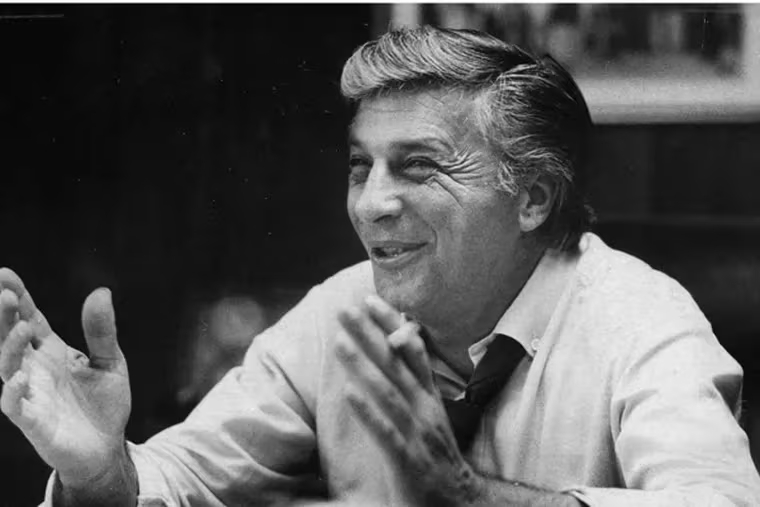

The operation was initiated by the head of the FBI’s New York office, Neil J. Welch. It was supported by the head of the Organized Crime Strike Force in New York, attorney Thomas Puccio.

When it began, the focus of the operation was the recovery of stolen works of art and securities.

The FBI enlisted the help of con-man Melvin Weinberg and his girlfriend and fellow con-artist, Evelyn Knight. Both were facing potential prison sentences for financial fraud, and believed that assisting the FBI would help their pending cases.

Weinburg, with the support of the FBI, created a company called Abdul Enterprises. This was presented as a company run by wealthy Arabs who were interested in stolen art. The owners of the company and its employees were all FBI agents.

At several meetings during 1978, disguised FBI agents distributed cash bribes. The FBI established a fund of over $1 million to provide the bribes. At each meeting, hidden cameras recorded everything that happened.

In late 1978, the focus of what had become known as ABSCAM (the Abdul Enterprise Scam) changed. At one meeting, a New York stock forger told the FBI “Sheiks” that he had a better idea.

He claimed to know senior politicians who, in return for hefty bribes, would issue licenses for the establishment of casinos.

Casinos were lucrative, but licenses were difficult to obtain. Unintentionally, the FBI seemed to have stumbled across an even bigger case.

ABSCAM became an investigation not into stolen art, but high level corruption.

ABSCAM Changes Focus

With the encouragement of his FBI handlers, Weinberg spread the word that his Middle-Eastern backers had a new target.

They were interested in becoming involved in the gambling industry in Atlantic City. To succeed, they needed contact with people who could provide licenses.

In response, Camden Mayor and New Jersey state senator Angelo Errichetti contacted Abdul Enterprises.

At a meeting recorded by hidden cameras, he told the “Sheiks” that he could “deliver Atlantic City.” But only on the payment of substantial bribes to Senators, Congressmen, and local politicians.

A series of meetings followed, all secretly filmed. Congressman Frank Thompson accepted a cash bribe of $50,000. He agreed to help with the acquisition of a casino license and with immigration for associates of Abdul Enterprises.

Several other Congressmen also accepted $50,000 bribes to help Abdul Enterprises. Three members of the Philadelphia City Council accepted bribes of $65,000.

An immigration official also accepted a bribe in return for promises to expedite the immigration of “Arabs.”

The FBI found itself in the middle of a potentially explosive scandal. It appeared that some of the most powerful politicians in America were willing to accept cash in exchange for favors. Then, in 1980, details of ABSCAM were leaked to the press.

This became a headline story in many popular U.S. newspapers and television news shows. As details of the operation emerged, support for bringing the accused to trial grew.

Between August 1980 and March 1981, a number of defendants would face trial for their part in this scandal.

The Trials

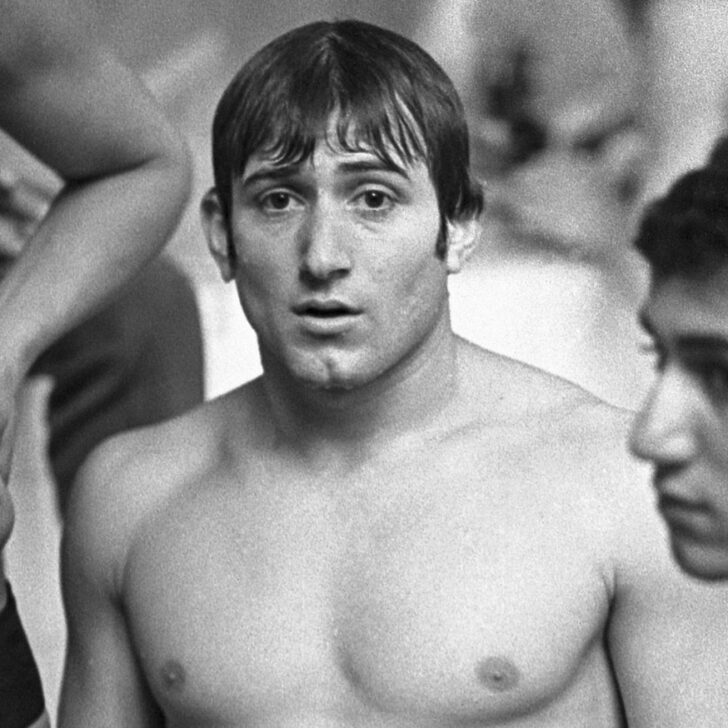

The first trial began on August 11th, 1980, in New York City. The defendants included Congressman Michael Myers and Angelo Errichetti, the Mayor of Camden.

Also indicted was Howard Criden, an attorney who accepted bribes on behalf of his client, Congressman John Murphy.

The first trial was followed by a series of others over the course of the next nine months.

These received massive coverage in the media, and most people were horrified by the apparent scale of the corruption involved. Most defendants were perceived to be guilty.

That was probably unsurprising. Evidence for the prosecution included the videotapes made by the FBI of bribes being handed over.

A stunned court watched as senior politicians or their representatives accepted wads of cash in return for promised favors.

Con-man Melvin Weinberg also gave evidence. During three days of testimony, he was grilled by the defense, who focused on his criminal past. It didn’t help – the video evidence against most of the defendants simply could not be denied.

Some defendants claimed that they had done nothing wrong. Congressman Michael Myers, for example, told the court that, though he had accepted the bribe, he hadn’t helped Abdul Enterprises. It was, he said, simply “easy money.”

The courts weren’t convinced by this argument. In total, 19 defendants were found guilty on charges of conspiracy and bribery. None of those indicted were acquitted.

However, not all Congressmen targeted by ABSCAM came to trial. John Murtha had met with disguised FBI agents but declined to accept a bribe “at this point.” He was not prosecuted and remained in Congress until his death in 2010.

Those found guilty included six Congressmen, one Senator (Harrison A. Williams) and members of the Philadelphia City Council.

Camden Mayor Angelo Errichetti, an Immigration Service Inspector and business associates of the public officials were also found guilty.

Sentences ranged from three to six years in prison with fines of $20,000 – $50,000. All the elected officials found guilty either resigned, were ejected from office, or lost at the next election.

Aftermath And Concerns

The evidence presented at the ABSCAM trials left no room for doubt on the guilt of defendants. But many people, including the trial judges, were troubled by the ethics of the FBI operation.

Perhaps otherwise honest men had been tempted by large bribes to commit crimes they would not otherwise have considered.

The involvement of Melvin Weinberg in planning and carrying out the operation also caused a great deal of unease. Weinberg was a convicted criminal. He escaped a prison sentence for his most recent crimes and was paid $150,000 by the FBI.

All the defendants appealed the verdicts in the ABSCAM trials. None were upheld, though judges criticized the operation itself as well as its oversight by the Department of Justice.

In 1982, the Senate established the Select Committee to Study Undercover Activities.

This committee issued a report in December 1982. This report didn’t directly examine ABSCAM, but looked more generally at undercover law enforcement activities.

It concluded that while such operations might be useful, there was a risk that they might “compromise law enforcement itself.”

While many people supported ABSCAM, many questioned its real purpose. The FBI had been the recipient of unfavorable reports by Congress in the 1970s.

The Church Committee reports focused on alleged brutality amongst law enforcement agencies, including the FBI.

Was ABSCAM nothing more than an act of revenge on the part of the FBI? Was the real purpose of this operation not to achieve justice but to discredit Congress? These questions were never fully resolved.

Congress passed three more sets of guidelines for undercover operations in 1983, 1989, and 2001. These were claimed to avoid accusations of entrapment.

But some people wondered whether these were simply an attempt to ensure that ABSCAM could never be repeated.

Conclusion

Viewed in terms of securing convictions, ABSCAM was a success. It uncovered corruption at the highest levels of the American government. For some elected officials, accepting “easy money” seemed almost routine.

However, this operation increased public unease, both at the integrity of government and the motives of the FBI. And to some people, the image of FBI agents disguised as wealthy Arabs was inescapably comic.

In 1982, a modified version of the popular video game Pac-Man was released. In this, the player took the role of a Congressman, collecting dollar bills while avoiding FBI agents. When American Hustle was released in 2013, it portrayed ABSCAM as a dark comedy.

Perhaps seeing this operation in comedic terms is understandable. The involvement of a convicted con-man and dressing FBI agents in over-exaggerated clothing certainly support that view.

But at its heart, there is nothing funny about ABSCAM.

You can view this as an operation that revealed corruption at the highest levels of U.S. politics. Or you can see it as an unscrupulous FBI operation intended to discredit otherwise honest men. Perhaps you can even see it as both.

Either way, ABSCAM was contentious and significant. Coming as it did just a few years after the resignation of President Richard Nixon, it reinforced perceptions of corruption.

The fact that the FBI had been willing to pay a convicted criminal for advice was also worrying.

Undercover law enforcement operations have certainly changed significantly as a direct result. No longer was it acceptable or permissible to tempt targets with large bribes.

Whether it reduced corruption is another question entirely. The willingness of many elected officials to take bribes was certainly startling.

But such things are generally done secretly, and we will never know whether ABSCAM made a lasting difference to corruption.

Sources

https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/abscam/

https://library.cqpress.com/cqalmanac/document.php?id=cqal80-1174797

Leave a comment