Today, North Korea is globally known, and sometimes feared, for its antagonism on the global stage. The Kim family, which rules over the nation with an iron fist, has threatened nuclear war with the world and manipulated the nation’s citizens into believing nothing is wrong.

But their totalitarian regime and threats of world destruction are the most drastic of their international offenses; even if they are small, there are other reasons for nations to hold North Korea at arms reach.

Sweden, for example, was personally insulted by North Korea when, in the 1970s, North Korea ordered 1000 Volvos from Sweden and refused to pay.

To this day, Sweden holds the country accountable for its payment, but no payment has ever been made. So how did this strange incident in international relations occur, where North Korea stole Volvos from Sweden?

In the mid-1970s, North Korea was emerging on the global stage as a potential new market for international trade. The country, as well as its southern counterpart, had spent two decades recovering from the Korean War.

While South Korea had assistance and economic aid from the United States and other Western nations, North Korea was largely alone, reliant on limited Western trade for its survival.

But, by 1974, North Korea had begun to turn itself into an industrious nation that held promise for outside countries seeking new markets to expand into.

They merely needed a bit of external investment for their economy to soar, and Sweden saw the opportunity to get in on the ground floor.

Opening North Korea To The West

Sweden became the first nation to invest wholeheartedly in the fledgling North Korean market, for which it has been rewarded, although not in the way expected.

Thanks to their economic investment and opening of relations, Sweden became the first nation to open an embassy in the communist nation of North Korea. This was a departure from the overarching anti-communist attitude that much of the Western world held during the Cold War.

This embassy was an oasis within the closed-off nation, a small window for a handful of Westerners to get a glimpse behind the curtain into the operations of North Korea.

The first ambassador to the new Swedish Embassy was Erik Cornell, a career politician who had also worked in Bonn (West Germany), Warsaw (Poland, although it was a satellite state of the USSR), and Ethiopia. Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea, was a new challenge for Cornell, though.

The city was cold and industrious, a far cry from the comforts of Europe or the warmth of Africa to which Cornell had become accustomed. The hustle and bustle of large European cities or popular African bazaars was absent in a city still learning to grow.

Cornell later recalled that there was not much to do in the city since an economy of cafes and restaurants was yet to emerge, so he was forced to remain at home or at work.

But this did not dampen his spirit; he was one of the only Westerners allowed within the country, and that excited him.

However, excitement slightly faded as Cornell realized that the golden goose of the North Korean market might actually be a sham shortly after his arrival.

How The Volvo 144 Became A Status Of Wealth In North Korea

In 1975, North Korea ordered mining equipment and 1000 Volvo 144s from the nation of Sweden, totaling over 70 million dollars. The mining equipment was placed in a warehouse and was almost never used, deteriorating quickly.

But the cars excited the residents of North Korea, who were largely removed from the outside world. Since they were constructed for driving in Sweden, the cars worked perfectly in Pyongyang with a similarly cold environment.

Compared to American vehicles, which at this point were designed to become obsolete every few years as a method of incentivizing always getting a new car, the Volvo 144 was designed to last many years and be a reliable ride.

The blocky, solid cars became a status symbol within North Korea, as those within the upper echelons of society had a new method of transportation around the city. Soon, every road in Pyongyang was dominated by Volvo 144s, veering every which way with reckless abandon.

With so few other cars on the road, the 1000 Volvos seemed to overtake the city. Urban Lehner, a journalist who visited North Korea for The Wall Street Journal in the late 80s, wrote about how the roads out of the city were basically empty except for the reckless Volvo drivers.

Drivers would chauffeur journalists around the city, becoming a staple of visits to North Korea.

Selling the cars to the North Koreans was supposed to be a great investment.

Providing vehicles to a city with very few was meant to incentivize open commerce and encourage the North Koreans to open themselves up completely to the global economy.

North Korea’s original intention was to utilize the new technology from the Western world to improve their industry and bolster the economy, returning the favor of investment through commerce.

North Korea even promised to pay the debts with the results of their new mining operations and other economic advances brought on by Western technology.

However, the North Koreans simply never paid. No one knows if they could not afford the cars or if they simply decided not to pay, but the $70 million charge incurred by the Volvos became a massive outstanding debt that continues to accrue interest.

Cornell believes that North Korea was unaware of how to conduct economic trade with countries outside of the communist bloc, which made it impossible for the country to succeed even with the external stimulus from Sweden.

Either way, North Korea has since remained largely disconnected from the global market.

Nowadays, approaching the 50th anniversary of when the cars originally arrived in North Korea, the Volvos are starting to show their age.

North Korea is still largely cut off from the global economy, so receiving parts to repair the vehicles is difficult, but many of the Volvos are still operational: a testament to their longevity and a fulfillment of their dedication to not rely on planned obsolescence as a business practice.

The cars have fallen from grace as a status symbol, although they continue to be useful in Pyongyang. Many of them continue to be useful even in old age, now operating as taxis and other service cars.

But more importantly, the Volvos serve as an important, constant reminder of the relationship between Sweden and North Korea.

Twice a year, the Swedes still send a reminder to Pyongyang about the payment that they owe for the Volvos, although every time, the North Korean government simply ignores the reminder.

Today, the money that North Korea owes, which was once a payment of 70 million dollars, has now ballooned with interest to over 300 million dollars.

For some nations, this unpaid debt may incite an international incident, but Sweden is renowned for its diplomatic maneuvering and has utilized the situation to their advantage.

Sweden has long represented communities that are disadvantaged in global conflicts.

During World War II, Sweden represented the interests of Japanese nationals in the United States after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and throughout the 20th century, represented Iran through various diplomatically tense moments.

Nowadays, Sweden acts as a mediator between North Korea and the Western world in the role of protective power, a role it also holds for Canada and Australia.

The embassy in Pyongyang steps in to assist with international incidents on behalf of these nations since they lack a relationship with North Korea, acting as an ambassador of goodwill.

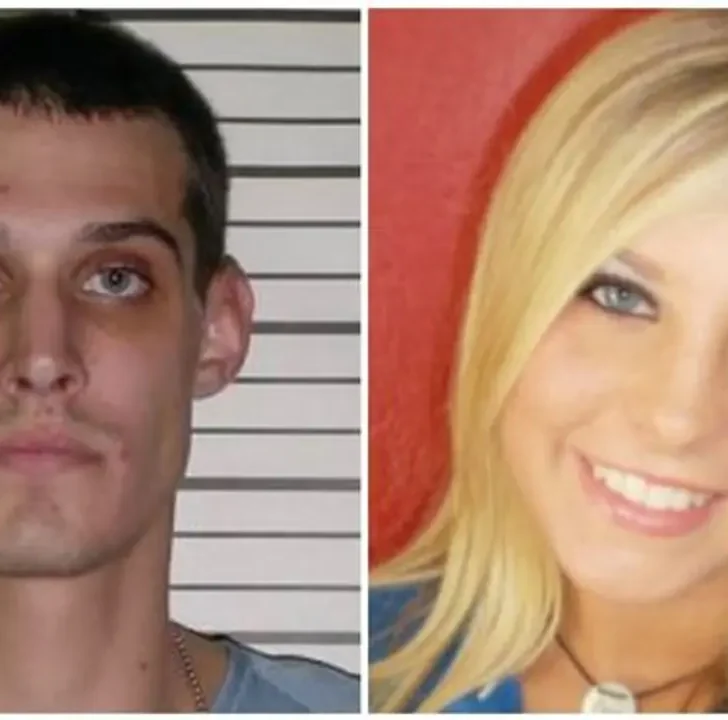

In 2009, an American journalist named Laura Ling and her colleague Euna Lee were apprehended by North Korean forces while filming a documentary on the border with China and detained for nearly four months.

The Swedish embassy stepped in to negotiate their release, and Ling recalls feeling immense relief upon seeing the Swedish ambassador because she realized he was the only person in the entire country fighting on her behalf.

While he was not a part of the team negotiating her release, the ambassador provided her with small reliefs such as books and medication, which ultimately made her detainment easier to handle.

Although they have lost out on many millions of dollars, Sweden has ultimately benefitted from the fact that North Korea stole 1000 Volvos.

Through this odd moment of weird history, the Swedes developed a unique relationship with the small communist nation of North Korea that is unparalleled by any other country in the world; a relationship that is maintained by the unspoken ritual of requesting payment that will never be fulfilled.

Leave a comment