Violet Jessop’s story is one of the most remarkable shipwreck survival stories in maritime history. Not only did she survive one shipwreck, but she survived three! And these weren’t just any shipwrecks.

They were three of the most famous ships of the 20th century: the RMS Titanic, RMS Olympic, and HMHS Britannic. Jessop’s story is one of coincidence and extraordinary luck–or was it bad luck?

In this article we will learn about the unsinkable Violet Jessop and how she managed to survive three maritime disasters and lived to write about it.

Early Life And Career Beginnings

Violet Constance Jessop was born in 1887 in Argentina to Irish immigrants. When she was 16 years old, her father died, forcing her mother to pack up the kids and move them back to Britain.

As she entered her 20s, Jessop entered the workforce to help support her family. She decided to follow in the footsteps of her big sister and began her career at sea when she got a job as a stewardess for the Royal Mail Line.

For the next couple of years, she worked hard and remained dedicated, knowing that one day it would pay off. And it did in 1910 when she became a stewardess for the prestigious White Star Line.

Surviving The RMS Olympic Collision

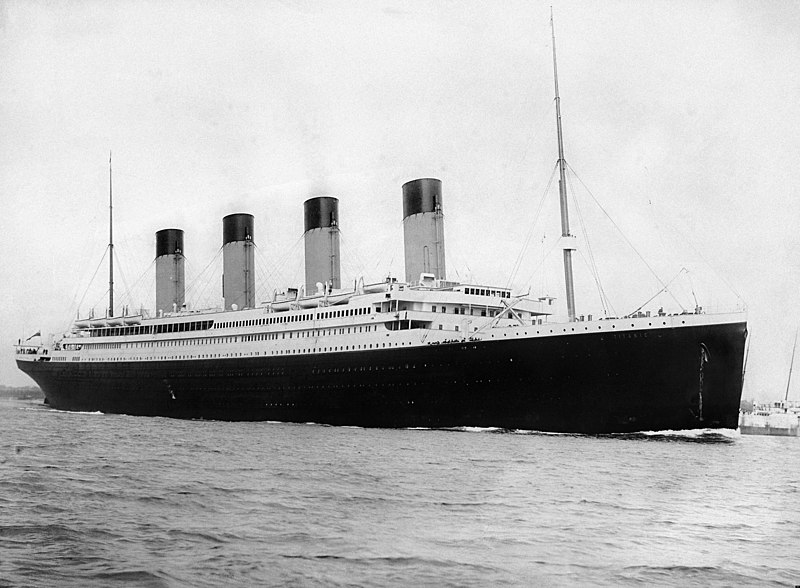

After joining the White Star Line family, Jessop was assigned as part of the crew of the RMS Olympic, the largest luxury liner at the time.

As the ship left Southampton on September 20, 1911, The Olympic attempted to overtake another vessel. As she tried to change course, the suction generated by the Olympic’s massive hull pulled the warship HMS Hawke closer.

The HMS Hawke was an Edgar-class cruiser that was specially designed for ramming ships and sinking them. The Hawke was not strong enough to pull away from the Olympic’s grasp and collided nose-first into the starboard side of the ship.

The impact damaged both the Olympic’s hull and the Hawke’s bow. Fortunately, there were no fatalities, and both ships were able to return to port for repairs. For some reason, Jessop left this event out of her memoirs. Probably because it wasn’t as exciting as what fate had in store for her next.

A Night To Remember: The Sinking Of The Titanic

She continued her tenure on the Olympic until April 1912, when the opportunity landed in her lap to join the crew of White Star Line’s newest and biggest ship, the RMS Titanic.

For Jessop, this must have felt like the peak of her career and proof of her hard work and determination.

The Titanic set sail on April 10, 1912. Jessop was awestruck. She was working on the most luxurious ship in the world, serving some of the richest and most powerful people in the world. It was a dream come true.

But that dream was about to turn into a nightmare. On the night of April 14, the Titanic was sailing through the ice-filled waters of the North Atlantic when she struck an iceberg.

At first, no one really noticed; most of the passengers were still asleep at the time. But as the crew assessed the damage, they realized that the ship was taking on a lot of water fast.

Due to a design flaw, the watertight compartments didn’t go all the way up and allowed for the water to flow over into the next compartment. By the time the crew had assessed the damage, too many of the compartments had filled.

The crew realized that the “unsinkable Titanic” was, in fact, going to sink.

Jessop jumped into action and helped passengers stay calm and organized as the lifeboats were loaded. As the situation worsened, Jessop was instructed to board a lifeboat herself to set an example and to encourage the non-English speaking passengers to follow.

Jessop boarded lifeboat 16 and was handed a baby to care for. Then, she and the rest of the passengers who were lucky enough to get a lifeboat helplessly watched on as the mighty ship slipped beneath the waves and took the lives of over 1500 people.

Hours later, Jessop and the other survivors were rescued by the RMS Carpathia.

Escaping The Sinking Of HMHS Britannic

The sinking of the HMHS Britannic marked Violet Jessop’s third brush with maritime disaster. The HMHS Britannic was the third of the White Star Line’s Olympic-class ocean liners and was supposed to be the grandest and largest of the three.

Like her sisters, she was intended to serve as a luxury passenger liner. Boasting enhancements based on the lessons learned from the Titanic’s tragic sinking in 1912, The Britannic included advanced safety features such as a double hull and greater lifeboat capacity.

The ship was designed to attract the wealthiest of the wealthy, boasting elaborate dining rooms, luxurious staterooms, and recreational facilities that included a gym and swimming pool.

However, by 1914 World War I had broken out. There was a great need for medical support for wounded soldiers returning from the front lines.

In 1915, before the Britannic could enter commercial service, it was requisitioned by the British government and converted into a hospital ship, renamed HMHS (His Majesty’s Hospital Ship) Britannic.

By November 21, 1916, the ship was in use as a hospital ship and Jessop had once again found her way onboard. This time working as a nurse treating wounded soldiers.

One morning, the ship was navigating through a high-risk zone in the Kea Channel when she hit an underwater German mine.

Despite the Britannic’s advanced double hull design, the explosion tore a large hole in the Britannic’s starboard bow. The damage was too much for the ship to take and she quickly filled with water.

Like the Titanic, The Britannic was equipped with watertight bulkhead doors designed to contain the water. However, some of these doors were reportedly left open to help nursing staff and other crew members, which allowed water to spread.

Jessop, along with other nurses and wounded soldiers, were herded into the lifeboats. However, the evacuation process turned into chaos as the ship sank rapidly and began to list.

Jessop, having done this twice before, knew the drill. She remained calm and got into a lifeboat.

As Jessop’s lifeboat was lowered, it drifted towards the massive propellers that were lifting out of the water. As the ship listed, the lifeboat was pulled towards the spinning blades.

Realizing the imminent danger she was in, Jessop made a split-second decision to jump out of the lifeboat and into the water, a good 15 to 30-foot drop.

Despite the crew’s efforts to save the ship, the Britannic sank in just under an hour after the explosion. Jessop found herself surrounded by oil, debris, and the cold sea.

Miraculously, Jessop managed to stay afloat and keep her head above water as she waited for someone to rescue her.

She was eventually rescued from the water and taken ashore. Her ordeal on the Britannic was the third and final shipwreck she survived.

Life After The Disasters

Despite the traumatic experiences of surviving both the Titanic and Britannic sinkings, Jessop stayed on as a stewardess. After World War I, she returned to work for the White Star Line and, later, the Red Star Line.

Violet Jessop continued to work at sea until she retired in the 1950s. Over the course of her career as a stewardess, she witnessed the rise and fall of the golden age of ocean liners and was there to see the dawn of commercial air travel.

In her later years, she moved to Great Ashfield in Suffolk, England where she led a quieter life.

Jessop’s retirement years were quiet and relaxing, but she couldn’t sit still for long. She had a passion for storytelling and eventually decided to write about her life experiences.

She wrote a memoir of her experiences titled “Titanic Survivor: The Newly Discovered Memoirs of Violet Jessop Who Survived Both the Titanic and Britannic Disasters.”

Jessop’s titles as a Titanic survivor and a Britannic survivor have made her a figure of mythic proportions in maritime history.

Reflecting on her life, Jessop combined a humble demeanor with a rather philosophical take on her extraordinary luck—or lack thereof, depending on how you look at it.

Despite her penchant for finding herself on sinking ships, she remained a private person, modestly sharing her tales without making too much fuss about her apparent indestructibility as an unsinkable stewardess.

Sources

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Violet_Jessop

https://www.encyclopedia-titanica.org/titanic-survivor/violet-constance-jessop.html

Leave a comment