During the Second World War, the Soviet Union and the United States were allies to defeat Nazi Germany. But quickly after the war ended, the uneasy partnership dissolved.

The communist Soviet Union and capitalist United States then spent nearly half a century in a global conflict called the Cold War.

The Cold War

Each side tried to prove that communism or capitalism was a better system. However, this war was not fought directly between the two nations. Instead, they supported military conflicts within other countries such as Korea or Vietnam to try and win them over.

Although boots on the ground was not the only way these two superpowers fought.

Both sides also developed extensive intelligence networks to spy on each other. And it was within the shady backrooms and political offices of Washington DC and Moscow that spies fought the true Cold War.

Espionage became the best tool for gaining the upper hand. Both nations raced to gain the upper hand, only to be undercut by the others’ spies.

For example, the Soviets were able to rapidly expand their nuclear development program to match the United States in just a few years, thanks to moles in the American scientific community.

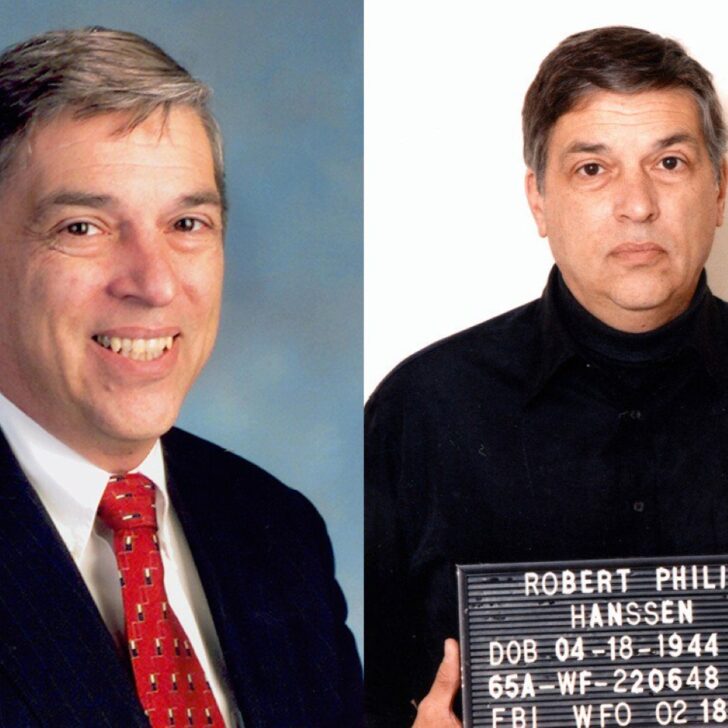

Famously, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were American citizens executed for espionage that provided atomic secrets to the USSR. They swore innocence to the end, making their deaths a controversial topic, but they stand as two of the most famous traitors in United States history.

On the other hand, the United States was able to decrypt Soviet transmissions in the 1940s that identified American spies, such as the Rosenbergs.

The United States military also developed new hardware for espionage called the U2 spy plane. After several years of gathering intelligence secretly, the USSR shot down one of the planes, causing an international incident.

One of the greatest feats of Soviet espionage came in the earliest days of the Cold War, before World War II even ended. On August 4, 1945, the Soviet Union sneakily gifted a United States politician a listening device that they used to spy on their opposing government for nearly a decade.

There’s A Bug In The House

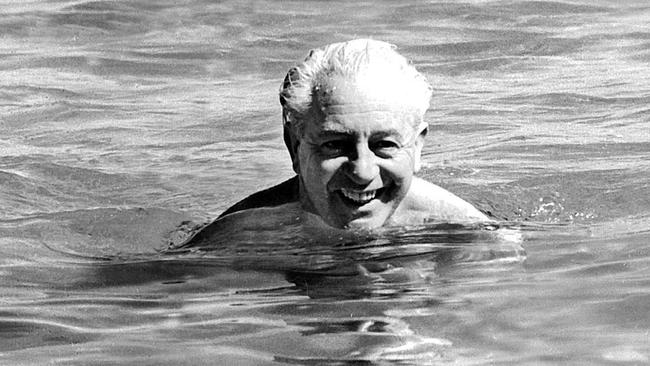

Ambassador W. Averell Harriman had resided in Moscow for two years at Spaso House. This residence had been the designated ambassador’s home for over a decade.

While the United States had not recognized the Soviet Union diplomatically until 1933, once it did the government quickly needed a property and leased the Spaso House starting in 1934.

The Vladimir Lenin All-Union Pioneer Organization, a school for gifted children in Moscow, met with the United States ambassador in the closing days of World War II in August of 1945.

As a gift of goodwill between the nations, whose allyship was tense, they offered a large carved seal of the United States. Nobody suspected a thing, since the gift was coming from a group of children.

The Great Seal, that became later known as The Thing, was accepted wholeheartedly and in good faith. Harriman hung it in the library of Spaso House. An ornately decorated space, the library was where meetings were held for officials to discuss confidential topics.

The giant seal fit in well as a representation of the nation the officials served. But little did the officials know that the generous gift would betray their confidence.

Since Spaso House is located less than a mile from the Kremlin, anti-espionage measures were already in effect. Although diplomatic relations were civil, both nations were aware of the others’ nefarious spying.

Despite the best efforts of United States counterintelligence though, it became clear within a few years that the Soviets were still somehow gathering information about the meetings held in the Spaso House library.

The device was not discovered until nearly seven years after it was originally hung in the library.

Several times, British and American radio workers realized that they were picking up the voices of political officials from the embassy and attempted to investigate. Officials swept multiple times for bugs, but no electronic recording devices were ever located.

How The Bug Was Finally Found

Finally, a US counterintelligence agent named Joseph Bezjian found the device after completing a sweep of the residence in 1952. Bezjian had Ambassador George Kennan broadcast a fake classified message to the United States as a test, in an attempt to capture how the Soviets were activating the device.

Using Ultra High Frequency (UHF) waves, Bezjian scanned the embassy. After narrowing the signal down to the library, he encouraged Kennan to continue the broadcast so he could conduct more tests.

Within four minutes of entering the library, he had identified the secret listening device and assessed how it worked. Bezjian found that hitting the seal with a specific frequency caused him to hear Kennan’s broadcast on the radio receiver.

Once the fake broadcast ended and it was safe from Soviet spies listening in, the counterintelligence officers pulled down the seal.

Once they opened the seal, the Thing intrigued them greatly. It had no electronic equipment attached: no circuits, no motherboard, and no source of power. So, how could it possibly relay radio signals? They had to find out.

The seal was placed in a diplomatic pouch and rapidly transported back to the United States, where the FBI was tasked with investigating. The Naval Research Laboratory did a full analysis of the device and produced a 35-page report with its findings.

What they found was astounding. The device did not record audio, which is why it did not have any electrical components. Instead, it was a broadcast device that relied on the vibrations of the inner panel to produce sound waves. It became known as a “passive cavity resonator.”

Just below the beak of the seal were small holes drilled to allow sound waves to enter the body of the seal. The waves would then vibrate a membrane within the seal. This is how the audio from the American politicians was “recorded.”

At the same time that meetings were vibrating the seal, a Soviet intelligence officer would be stationed nearby. They would point a remote radio wave at the seal to activate its broadcasting capability.

Once activated, the seal would send out a signal one harmony higher than the vibration it was currently experiencing. With a receiver tuned to the correct wavelength, the Soviets had a direct window into the Spaso House library.

By translating the sound back down one harmonic step, they were able to hear every word the Americans were saying.

Once the Soviets realized that their device had been discovered, they quickly invented ways to counter a similar device being deployed in their own offices. This did not deter Western scientists, though.

Researchers in the United States, Britain, and Sweden all worked to develop similar wavelength technologies.

What Did The U.S. Do In Response?

The original device was created by Soviet scientist Leon Theremin. Theremin is most famous for creating the instrument which shares his last name.

The device is comprised of two metal antennas and a field of radio waves. The antennas do not broadcast sound themselves but distort the sound emitted by the device.

Together, the antennas measure where the musician’s hands are placed above the instrument. The performer can control the frequency with one hand and the volume with the other. The device operates similarly to the Thing in that it measures wavelength frequency over distance to create sound.

This new technology of manipulating radio waves intrigued the West. Passive elements, such as the vibrating membrane that required an activating frequency to operate, became a subject of temporary interest for the CIA for a decade.

However, the level of effort and resources needed to consistently produce the specific radio waves at a distance viable for espionage made the technology inefficient for the intelligence field.

As with many military technological advancements though, it made its way to the private sector and is now widespread. RFID chips utilize the same technology, which allows fobs and security keys to operate by proximity in lieu of using a physical key.

NFC, the technology used for tap-to-pay technology in phones, also utilizes similar technology but with a smaller range.

The Thing was a great achievement for Soviet espionage and its discovery is an essential moment of Cold War espionage history. It placed the Soviets at an advantage in the early years of the conflict, alongside their other spies and infiltration.

By the time the United States even discovered the device, the Soviets were prepared to counter the technology so it could not be effectively deployed back.

Today, a replica of the Thing hangs in the Spy Museum in Washington DC, along with various other contraptions and technologies that have gathered intelligence covertly over the years.

Leave a comment