In 1942, a number of aerial battles took place in the skies over the beleaguered city of Stalingrad between aircraft of the German Luftwaffe and the Red Air Force.

During one of these, a Soviet Yak fighter swooped down on a German Ju 88 bomber and quickly shot it down.

Next, the Yak turned to engage one of the escorting fighters, a Messerschmitt Bf 109, one of Nazi Germany’s best fighters, and this one was flown by Unteroffizier Erwin Maier, an experienced pilot who had already shot down 11 enemy aircraft.

The Soviet pilot was clinical, professional and fast and in moments, Maier found his aircraft plummeting to the ground out of control. He was able to bail out and was captured.

Later, he was allowed to meet the fighter pilot who had shot him down and was more than a little surprised and disconcerted to discover that this was a petite, blonde, 21-year-old Russian woman.

This is the true story of Lydia Litvyak, a Red Air Force fighter pilot and one of only a handful of female fighter aces in World War Two.

Early Life

Lydia (or Lilya) Vladimirovna Litvyak was born in Moscow in 1921, and her childhood was conventional in the context of the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s.

She joined the Little Octobrists at the age of seven before graduating to the Young Pioneers, a compulsory Communist youth movement, when she reached the age of nine. At 14, she joined the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League (Komsomol).

Litvyak was educated as a fervent Communist, and it must have been a dreadful shock when her father became one of almost two million people who “disappeared” during the Stalinist purges of the 1930s.

We don’t know why or what happened to him, though it seems very likely that he, like so many others, perished in one of the infamous “gulags”.

This doesn’t seem to have reduced Lydia’s belief in Communism – if anything, she seemed to become even more fervent, perhaps in an effort to clear the name of her family after the arrest of her father.

At the age of 15, she began to learn to fly, possibly inspired by the well-publicised achievements of Marina Raskova, the first qualified female navigator to serve in the Red Air Force and a crew member on several record-breaking long-distance flights.

In the 1930s, the Soviet Union was virtually the only country in the world where women were not just permitted to serve in the armed forces but to take on the same front-line roles as their male counterparts.

A new Soviet Constitution, enacted in 1936, gave women the same civil rights as men, and many joined the Red Army and Air Force. Lydia did not, but by the late 1930s, she was an experienced flyer who held a civil instructors’ licence.

Then, in June 1941, Nazi Germany launched a surprise invasion of the Soviet Union. In the first months of this new war, the Red Army and Air Force suffered catastrophic losses, and the Nazis pushed east, almost to Moscow itself.

A call went out for volunteers to serve in the Armed Forces. Lydia was one of over 800,000 Soviet women who answered this call.

In The Red Air Force

As the most famous female aviator in the Soviet Union, Marina Raskova was given the responsibility of forming Air Group 122, an all-female combat aviation unit comprising three regiments.

Those three regiments were: the 587th Bomber Regiment, the 588th Night Bomber Regiment (which became famous amongst German troops as the Nachthexen, Night Witches), and the most capable female pilots of all were assigned to the 586th Fighter Regiment.

Lydia applied to join the 586th Fighter Regiment, but to her disappointment, she was turned down because she didn’t have enough flying experience. She solved this problem by forging her flying papers to show an additional 100 hours of flying time.

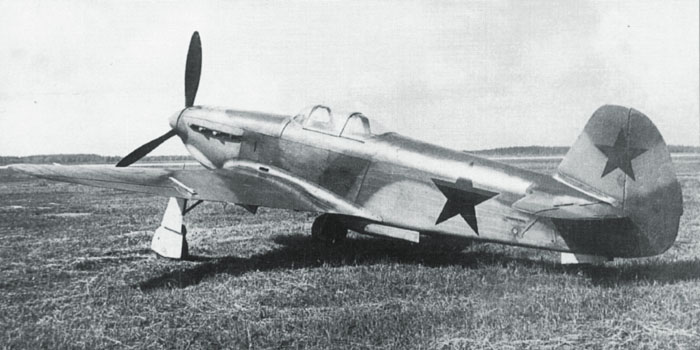

She reapplied, and this time, she was accepted. Lydia found herself flying the Yakovlev Yak-1, a fast, manoeuvrable monoplane fighter adopted by the Red Air Force in 1940.

Like most single-seat fighters, the Yak-1 wasn’t particularly easy to fly, but Lydia quickly proved to be a skilled and fearless pilot.

In early 1942, she completed her training and began flying combat missions with her squadron near the city of Saratov on the Volga River. She proved to be a courageous pilot and an asset to the regiment. On the ground, she was equally fearless, sometimes to the chagrin of her superiors.

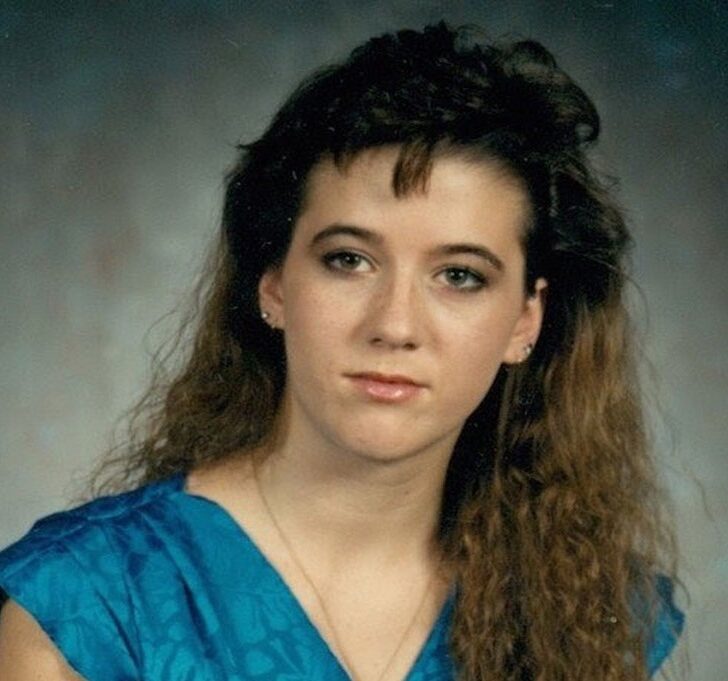

Lydia refused to cut her brown curly hair short like the other female pilots. When she was reprimanded, she responded by buying a bottle of peroxide and dying her hair a vivid blonde. She added a stylish fur collar to her uniform, something that was strictly against regulations.

During her training, Lydia was found to be absent without leave one evening. When questioned, she freely admitted that she had gone dancing with soldiers from a nearby barracks.

She even admitted to forging her flying record to be accepted in the regiment, but her abundance of spirit and natural talent allowed her to stay.

Later, in 1942, Lydia and other female pilots from the 586th were transferred to join a male fighter squadron to take part in the defence of the city of Stalingrad.

Few of the male pilots were enthusiastic about having female comrades – some allegedly refused to fly in aircraft repaired or serviced by female ground crew also transferred from the 586th.

However, Lydia’s skill and courage earned her a place in the regiment and the respect of her male comrades, and it was during this time that Lydia encountered Nazi aircraft of Jagdgeschwader 53 and shot down Unteroffizier Erwin Maier.

In January 1943, Lydia was transferred once again to another male fighter regiment, the 296th. There, it is claimed that she met and fell in love with the regiment leader, Alexey Salomatin.

Some accounts suggest that the two planned to marry, but before that could happen, Lydia was involved in her most challenging air battle yet when she, flying alone, encountered a flight of six Nazi Messerschmitt fighters.

She managed to shoot down two of them before she was also shot down and suffered a serious injury to her leg.

By this time, Soviet propaganda was beginning to regularly feature Lydia (they gave her the name “The White Rose of Stalingrad”), and the story of a single female Soviet fighter pilot taking on six Nazis was simply too good to miss.

Lydia was widely featured in Soviet newspaper articles and, when Allied nations picked up the story, around the world.

After recuperating from her injuries, she returned to the regiment to discover that she had been promoted to the rank of senior lieutenant.

Her happiness at returning to the regiment was short-lived. Soon after, Alexey Salomatin was killed in a landing accident. Lydia was promoted once again to take on his role as regiment leader, and she continued flying in combat through the summer of 1943.

A Mysterious End

On 1st August 1943, Lydia took off on a combat mission over Dmitreivka, Ukraine. She never returned. The official version is that she was shot down and killed, though neither her body nor the wreck of her aircraft were found.

Official reports claimed that she had been shot down while attacking a large formation of German aircraft.

That version of events is not accepted by everyone. Some accounts suggest that Lydia either bailed out of her stricken aircraft or was able to make a successful crash-landing and that she was then taken prisoner by German forces.

At least one other Soviet fighter pilot claimed that he had seen Lydia in a German POW camp after her disappearance.

That seemed to be disproved when the remains of a Soviet fighter pilot were recovered in 1979 and identified as Lydia, though this too is disputed. In 1990, Lydia was posthumously awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union, the highest award for military valour.

In 2000, Swiss television broadcast an interview with an elderly former female Soviet fighter pilot who had served in the Red Air Force during World War Two.

The woman, who didn’t give her Russian name, was married and living in Switzerland with her three children. A female former pilot of Air Group 122 saw the broadcast and claimed that the woman was Lydia Litvyak.

Conclusion

During World War Two, Lydia Litvyak was claimed to have shot down at least 12 German aircraft, making her an ace (a fighter pilot who shoots down five or more enemy aircraft) and officially the highest-scoring female pilot in history.

Since the war, that claim has been challenged, with some people suggesting that the actual number of aircraft she shot down was inflated by Soviet propaganda and that another female pilot in the 586th Fighter Regiment, Yekaterina Budanova, may actually have shot down more enemy aircraft.

In the end, precise numbers probably don’t matter. Lydia Litvyak succeeded in a military career dominated by men.

No other nation in World War II had female fighter pilots, and Lydia was extremely successful in shooting down more aircraft than most of her male counterparts.

Whether she died in combat in 1943 or survived, Lydia Litvyak was genuinely extraordinary.

Sources

https://www.omaka.org.nz/articles/lydia-litvyak-top-female-fighter-ace

Leave a comment