The Apollo was intended to be America’s final step to get humans on the Moon. And the deadline was coming up quickly.

Promised at the beginning of the 1960s by President Kennedy that America would land humans on the Moon before 1970, NASA was working busily to make this a reality.

However, in their rush to meet this arbitrary deadline, a disaster struck the Apollo program that reminded everyone of the true dangers of venturing into space.

Background

After losing the first leg of the space race to the Soviet Union’s Sputnik, the United States created the Mercury space program in 1958.

The ultimate goal of the US space exploration efforts was the eventual landing of a man on the Moon. But before that, there would be several stepping stones to get there. The first of these was the Mercury space program.

The goal of the Mercury program was to send a human into space and then get that person to return to Earth safely.

The program was crucial to fill in many of the knowledge gaps of the time surrounding space travel, including what supporting systems were needed in flight, the physiological effects of space travel, creating reliable equipment, and the fundamentals of piloting a craft in space.

The Mercury program was a resounding success. Beginning with Alan Shephard’s landmark flight of being the first American in space, the program continued for several years, concluding with John Glenn’s orbit around the Earth in February 1962.

Once these early objectives were met, the US space program transitioned to the next phase: the Gemini program.

The Gemini program was the next step to the Apollo program. Running from 1961 to 1966, its goals were to build upon the lessons learned from the Mercury program and work out expected problems in the Apollo program.

The astronauts who served during this time focused many of their efforts on more than just piloting the spacecraft. Now that the US had proven a manned space flight was possible, the next logical step was determining what actions were needed to land on the Moon. And figuring that out was not easy.

There were numerous proposals for how to land on the Moon. There were four general schools of thought: landing directly on the Moon and taking off, launching different aircraft into space and assembling a craft, or launching a recovery vehicle to the Moon.

Lastly, there was the idea to launch a vehicle that orbited the Moon, send a lunar lander, leave the command module orbiting the Moon, and then dock with it to return to Earth.

At the time, NASA scientists were unsure which plan to choose, so some of the Gemini program’s primary focus areas were solving some common issues between each idea.

Some of these issues included working in the vacuum of space, docking and redocking aircraft in space, returning to Earth, and spending a longer time in space.

The program also introduced the concept of having at least two astronauts present in the aircraft since all the Mercury missions had been solo flights.

Overall, the program was a resounding success and paved the way for the Apollo program to continue.

The Astronauts

When NASA announced who would be on the mission in March 1966, the crew they picked was undoubtedly qualified for the job.

Because of the dangerousness of what Apollo was supposed to accomplish, they wanted to stack the first mission to the Moon with as much experience as possible. For the crew that was selected as the primary crew, these were Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Edward “Ed” White, and Roger Chaffee.

Gus Grissom was the most experienced astronaut in the group and, as such, was named the mission commander. He was a career Air Force pilot who had seen plenty of combat during the Korean War, which won him numerous awards for bravery and airmanship.

Grissom tested his piloting skills during his first space flight during the Mercury program, where he earned his place in history as part of the Mercury Seven.

Completing a second space flight during the Gemini program, Grissom was ready to assume the helm of AS-204, as it was officially known before the crew nicknamed the mission Apollo 1.

The second most senior person on the mission was Ed White. A West Point graduate, White was able to be commissioned into the US Air Force, where he logged almost 3,000 flight hours before being selected as an astronaut for the Gemini program.

White made history as the first human ever to perform work outside a spacecraft, also known as a spacewalk, in 1965. After achieving international fame, NASA selected him as the senior pilot for Apollo 1.

Rounding out the crew was Roger Chaffee. A career Naval Aviator, he was the most junior person both in his military service and astronaut experience. However, he had a strong engineering background, which served him well as a capsule commander during the Gemini program.

These personnel assisted the flight crews from the ground. Additionally, he and Grissom had numerous flights together, taking aerial photographs of Saturn rockets in testing. So, though the most junior, he was undoubtedly well-qualified for the role.

With the crew selected, they began training.

Preparations For Apollo 1 Launch

Though NASA officially announced the crew compositions in March 1966, the primary and backup crews began preparing for their historic spaceflight months before.

Beginning with countless hours of classroom instruction, the astronauts received hundreds of hours of lectures on topics like celestial navigation, human physiology in flight, and learning the various systems of the new Command Module and Saturn rocket, among other topics.

Besides the classroom, the crew continued practical training as well. Starting in the pool at a local Air Force base, the crew began practicing egressing from their module upon returning to Earth.

They later practiced it numerous times in the Gulf of Mexico, where they had to ditch their module and await rescue by the Coast Guard.

In addition to this training, the crew also conducted numerous pressure tests of their suits and module at the Manned Spacecraft Operations Center at the Kennedy Space Center.

The crew also frequently traveled to Downey, California, to run test flights in the simulators by the module’s manufacturer, North American Aviation. After a year of training, the new year of 1967 saw the plans for the historic flight being finalized.

The primary purpose of Apollo 1 would not be to land on the Moon. However, it was going to break another record.

The mission was supposed to last for 14 days and orbit the Earth 208 times.

While in orbit, the crew was going to conduct a series of nine experiments that were meant to answer technological, medical, and scientific questions. Additionally, the crew was going to test-fire the new service propulsion system engine.

The purpose of the engine, dubbed SPS, was to lift the lunar module off the Moon’s surface to reconnect with the command module for a return trip back to Earth. The crew would also practice maneuvers to enter and leave Earth’s orbit.

With these lofty goals in mind, the launch was slated for February 21, 1967, and end on March 7. Though mission control would monitor the flight after every orbit, it was highly anticipated the mission would make history.

With the crews having to work through hundreds of engineering and design changes to the command module, the crews were working around the clock to accommodate tests for their every evolving craft. That is what they did on January 27, 1967, when disaster struck.

Disaster Strikes

In the afternoon of January 27, the Apollo 1 crew boarded their command module on Pad 34 at the Cape Kennedy Space Center. The test’s main purpose was to see if the command module could operate under its own power without any external power from umbilicals or cables attached.

The test started off slow. After the crew remarked about an odd smell in the cabin, the test was stopped for several hours while technicians examined the craft to ensure it was safe. After deeming it safe, the test continued when the crew continued to have difficulties communicating with mission control.

After stopping the test once again to fix the communications issue, the crew returned to the mission countdown. A fire suddenly broke out as they went through their preflight checklist.

There are differing opinions about what was exactly said or happened in those first few moments. The incident’s audio recording shows that Grissom was possibly the first to notice a fire or that something was burning.

The garbled transmission lasted just five seconds before ending with a shriek of pain. Ground personnel soon swarmed the craft, but it took them five minutes to open the hatch and another minute to extinguish the flames.

As thick black smoke poured out of the craft, it would be another few minutes before they realized the horror of what had happened.

Inside the burned-out cabin, all three astronauts were dead.

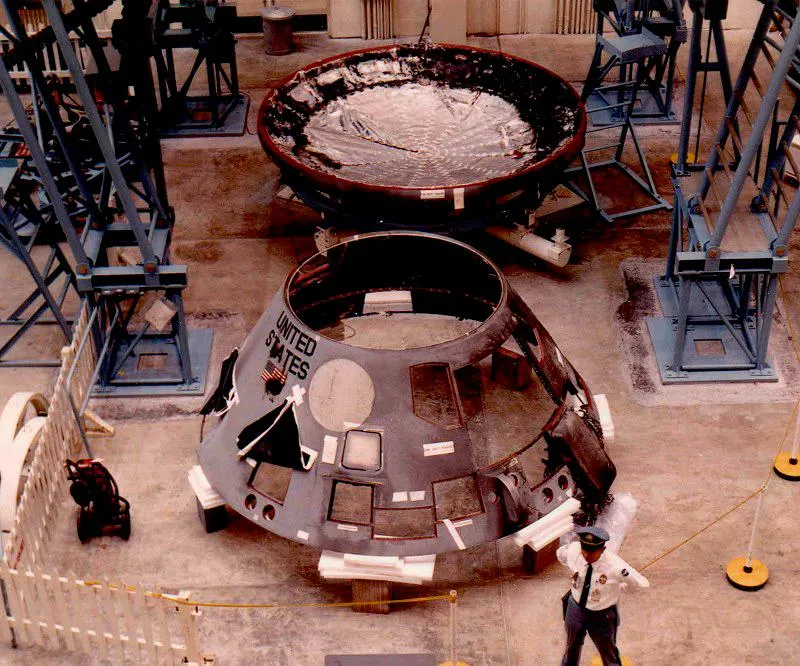

After closing off the scene, the investigation began immediately, with all documents and recordings being seized as well as hundreds of photos being taken of the craft before removing the astronauts’ bodies almost eight hours later.

Autopsies would confirm that all three men died of carbon monoxide poisoning despite their horrible burn injuries, which medical examiners deemed were still likely survivable.

But what caused the fire?

Aftermath of the Fire

After the tragedy, a full-blown investigation was carried out. Summarizing the several hundred-page report to its root causes shows that three main factors aligned to make the incident happen.

Firstly, a still unexplained electrical fire broke out in the module. Secondly, because the atmosphere inside the module was pure oxygen, the likelihood of a catastrophic fire breaking out was extremely high.

Lastly, the way the exit hatch was set up swung inward, so when the astronauts tried to escape from the module, they were unable to pull the hatch open against the greatly increased pressure inside the cabin.

Why NASA chose the extremely flammable atmosphere and its knowledge of its dangers became two of the main points of contention in the political fallout afterwards.

Numerous close calls had happened before, and though the reasoning for using pure oxygen was sound, namely, it was lighter and less dangerous than nitrogen-rich ones, the purported knowledge of the dangers in the Phillips report greatly damaged NASA’s reputation.

Conclusion

Despite the tragedy of January 27, the loss of the three astronauts inevitably taught many lessons learned that made manned spaceflight even safer.

Though Apollo 1 never took to the skies, their legacy was carried on by fellow astronauts who continued their dream.

Ultimately, the lessons learned from their loss proved critical in putting a man on the Moon just a few years later.

Sources

https://www.nasa.gov/history/55-years-ago-the-apollo-1-fire-and-its-aftermath/

https://archive.org/details/apolloprogramsum00unse/page/84/mode/2up?view=theater

https://archive.org/details/apollo-spacecraft-chronology-1/page/58/mode/2up

Leave a comment