Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, as the old adage goes. But how do we know what is beautiful and what is not?

Beauty is defined by the cultural context in which it exists. To many, European or American beauty standards may seem standard, since global media centers on these regions.

There is also an expansive beauty industry that has commercialized being attractive within these standards.

Viral influencers and celebrities are constantly passing along tips and promoting products guaranteed to make you more beautiful.

However, other nations value different characteristics that make someone beautiful. Bushy eyebrows or curvier bodies are valued in various cultures outside of the Eurocentric world.

More drastically, many cultures promote specific body alterations to make people more attractive.

While tattoos and piercings are common body alterations, there are examples of more drastic alterations. For over a millennium, Chinese women practiced the act of footbinding, as tiny feet were desired.

This involved tightly binding the feet of young girls to alter their shape and size.

The practice finally ended in the early 20th century after a long campaign condemning the act. However, the long history of foot binding represents issues of ethnicity, gender, and power throughout a millennium of Chinese history.

Origins Of Foot Binding

The exact origins of foot binding are unclear. Historians have found textual references to foot binding that date back as early as the 10th century AD, although the practice did not become popularized until later.

The earliest archeological evidence demonstrating the practice was found in the tombs of Huang Sheng and Madame Zhou, who died in the mid-to-late 13th century.

Although shaped differently than later examples, these women’s small feet were still bound and placed in tiny slippers that they were buried in.

Multiple stories exist that depict the potential origins of the practice, although they are all legends with no corroborating evidence.

Most notable of these legends is the story of Yao Niang, concubine to Emperor Li Yu of the Southern Tang in the 10th century.

The emperor supposedly asked her to bind her feet in the shape of crescent moons and dance on a golden lotus mural made of precious stones. Her dance was evidently so beautiful that the Chinese elite sought to emulate the practice.

The small feet resulting from binding became known as “lotus feet,” tying together the tale of Yao Niang and the Buddhist legend of Padmavati, whose footsteps created lotuses.

As the Chinese upper class perfected their methods of binding feet, the result came to symbolize femininity and beauty in Chinese society.

As with all beauty practices, it eventually made its way to the lower classes of society. By the 14th century, women all across China were binding their feet in an attempt to become as beautiful as possible.

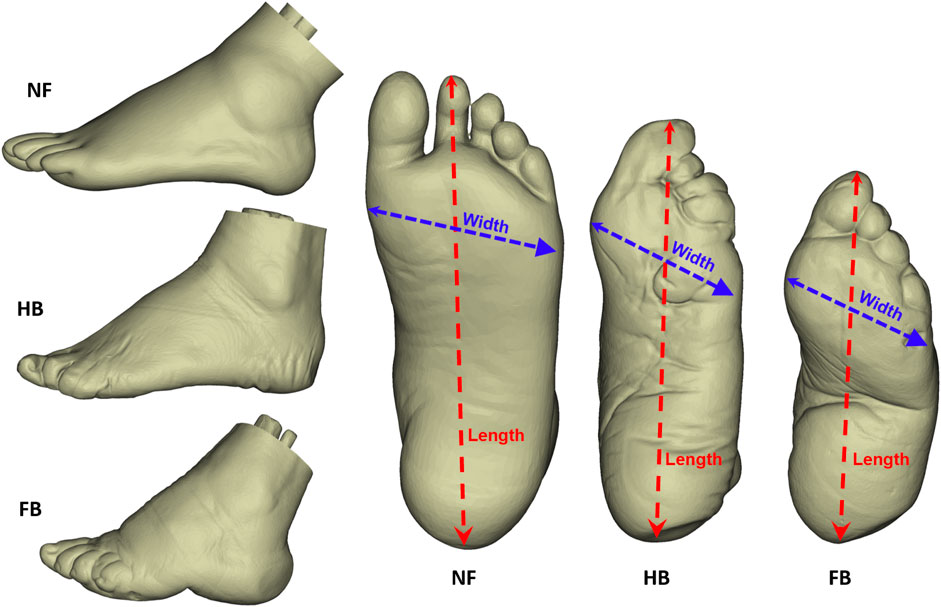

The Process And Its Effects

Foot binding began at a very early age, typically between the ages of four and nine. At this point, young girls’ feet were still more malleable, which meant the process of reshaping the foot was easier.

Parents typically waited for the winter when the girls’ toes would be numb, in an attempt to lessen the pain of the process.

To start, they would soak the feet in a mixture of herbs and animal blood to soften the feet. Then, they would cut the toenails back as far as possible to prevent future ingrown nails.

Finally, all but the big toe were curled under the sole and tightly bound by cloth until many of the bones of the foot were broken. Each of the toes and the arch would heal in a smaller shape.

The feet were then regularly unbound, cleaned, and cared for, then rebound more tightly to maintain the compact form.

Over the years, the exact shape and form of the bound feet changed as the practice evolved. But by the 16th century, the standard ideal foot length was about three inches long and was called the “golden lotus.”

Unsurprisingly, binding feet to only three inches long caused a wide array of health problems.

The women who were forced to bind their feet spent their entire lives in constant pain. Incorrect care could lead to infections or dying flesh, while paralysis and disability were common.

And yet, the infatuating desire to achieve peak beauty perpetuated the practice for centuries.

Cultural Significance And Symbolism

Bound feet were first and foremost a symbol of beauty in Chinese culture. Women with bound feet believed they were approaching a spiritual level of beauty.

Using binding to make feet smaller was similar in practice to intense corsets in Western culture. The focus was on feet instead of the waist, but wearing tight garments to alter the body and become more beautiful was not unique to China.

The practice could also be interpreted as a representation of gender in China. Bound feet were exclusive to women, who used the practice to attract a partner and whose feet became taboo in a way similar to genitalia.

The forbidden feature became enticing in its mystery. Some reports also describe how the bound feet caused women to walk more sensually.

Class divisions also became clear when looking at who bound their feet. For centuries, only the most elite, upper-class citizens of China were able to bind feet effectively.

It required constant upkeep and resources, which resulted in lower-class foot bindings being looser and less effective. Either way, foot binding ultimately debilitated and disabled its subjects in many ways.

For centuries, foot binding represented an immense level of wealth, sacrificing the ability to work for beauty. As the practice became more widespread, though, those in the lower classes could not afford to give up work; instead, they adapted.

Those who had their feet bound typically worked in domestic or urban roles that did not require as much physical labor since their feet restricted their movement.

The industrialized northern region of China saw much more widespread foot binding as a result.

Meanwhile, the agricultural southern region saw foot binding restricted to the elites who were not forced to farm rice fields, where sure footing was required.

Foot binding also became an ethnic differentiator, with the Han people subscribing to the practice while the Manchu and Mongols did not.

Finally, foot binding also represented the Confucian values of obedience and submission. Women who experienced the daily torture of foot binding were believed to be more reliant on their families and husbands.

The discipline and control needed to suffer in such a way implied that the woman would fulfill the role of loyal wife easily.

The sensual or Confucian nature of some accounts regarding bound feet has led many to believe that it was exclusively a service to men: women making themselves more attractive or more dependent on their partner.

However, some counter this argument by claiming that the practice was an active choice by women to obtain beauty in their own way, similar to debates over wearing makeup today.

Resistance And Decline

The practice of footbinding was subject to criticism even before the practice was banned in the early 20th century. By the late 19th century, the practice was actively being opposed by many.

As China opened to the Western world and admitted missionaries, the practice became even more taboo. Islamic leaders felt that foot binding interfered with the divine plan for the world, while Christians saw the practice as barbaric and advocated for its end.

In the late 19th century, early Chinese feminist Qiu Jin unbound her own feet and spent her life opposing the practice.

She advocated for women to get an education and fight for their independence, rebelling against the passivity and obedience that bound feet encouraged.

Societies and other organizations were created in opposition to the practice as part of a broader cultural shift within China during this period. With such widespread cultural opposition, the newly formed Republic of China banned footbinding in 1912.

While enforcement was haphazard across the rural areas of China, the practice all but died out by the mid-20th century.

The last case of footbinding was reported in 1957, and the last factory producing lotus shoes was closed down in 1999.

A Lasting Legacy

Although footbinding is no longer a legal practice, it has not fully disappeared.

It was practiced so recently that there are still a few old women in China whose feet were bound in their youth. The social and cultural implications of such a practice are still debated by scholars.

On the surface, the practice of binding feet was about creating a more beautiful woman. Drawn from legend, the standard of small feet was so enticing that women subjected themselves to immense pain to become more beautiful.

However, studying foot binding also calls into question various scholarly topics such as ethnicity, gender, class, and power.

The practice intersected with each of these topics and assisted in redefining Chinese society for over 1000 years.

Sources

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/why-footbinding-persisted-china-millennium-180953971

https://www.npr.org/2007/03/19/8966942/painful-memories-for-chinas-footbinding-survivors

Leave a comment