In the annals of American history, there is arguably no other place that engenders more fear when spoken than the name Andersonville.

This Civil War prison was the home to nearly 45,000 Union prisoners of war during the conflict and the final resting place for about 13,000 of them.

What is more incredible beyond the fact that new prisoners had a 28% chance of perishing after arriving at Andersonville was that the vast majority of these deaths occurred during a six-month period from February to August of 1864.

Because of its reputation, numerous accounts have emerged from imposters and apologists regarding the conditions and what happened at Andersonville.

The reason for this lies in the fact that claiming to have survived the place was a badge of honor many veterans sought to wear to embellish what they accomplished after the war. So, what really is the truth?

Civil War Background

Beginning in April 1861, the Civil War remains one of the most important events in American history.

Due to the issue of slavery, with Southern states believing it should continue while Northern states believed it should be at least limited and gradually abolished, the legislatures of eleven southern states gradually seceded from the Union after the election of President Abraham Lincoln.

Southerners believed Lincoln would abolish slavery, and they seceded to protect this “peculiar institution.”

The fighting quickly surpassed both side’s expectations for brutality and size. Soon, both sides began placing hundreds of thousands and eventually millions of men under arms.

With such large armies, it was not uncommon for hundreds of thousands of men to participate in some of the largest battles of the war. With such vast numbers of men, there were high casualty figures, including hundreds of thousands of prisoners on both sides.

During the first two years of the war, both sides had informal exchanges of prisoners known as the Dix-Hill cartel. These exchanges saw nearly 500,000 prisoners of war exchanged over a two-year period.

However, as the war dragged into its second year with no end in sight, the attitude in the country changed.

Both sides began transitioning in 1863 from an organized war to a total war mindset. As part of this mindset, prisoner exchanges slowly came to a trickle and eventually stopped.

This then caused the creation of the majority of the war’s infamous prison camps.

Why Andersonville?

By the summer of 1863, the formal prisoner exchanges that had been taking place under the Dix-Hill cartel had all but ceased.

This was largely due because the North demanded that Black prisoners be treated the same as their white counterparts, while Confederates argued they were escaped slaves and would be treated as such.

Because of the breakdown in exchanges, which had already seen about half a million prisoners exchanged, the Confederacy began looking into building a large, permanent prison.

But there was just one problem. The prison could not be located near any major population center.

Southern fears of a mass prisoner escape that would inevitably fuel a slave revolt were quite profound.

The site would also have to be close to a railhead to allow the easy transfer of new prisoners and, supposedly, the bringing of provisions. Lastly, the camp needed to be far away from the path of potential Federal cavalry raids.

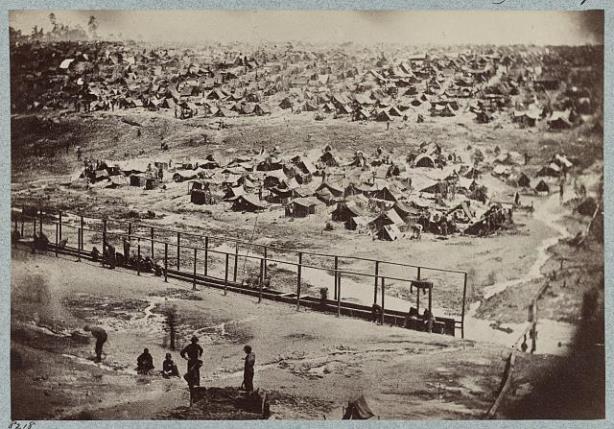

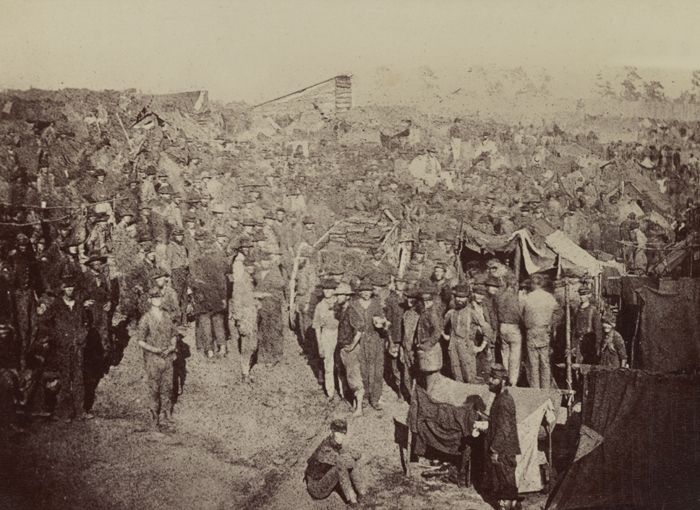

After looking around for several months, a site was finally chosen at the end of 1863. Construction began by impressing 900 slaves to build the original stockade that measured 1620 feet by 779 feet.

The stockade had a creek that ran through the middle of it that was supposed to serve the prisoners’ fresh water needs. But what would the new place be called?

Andersonville was not the official name for the location. Officially called Camp Sumter, the original site was located in what was then Sumter County and what is today Macon County in the southwest part of Georgia.

The area was then and is today incredibly sparsely populated. Back then, around 70 people chose to make the area their home, and the only reason for the settlements was the Anderson railway station, the area’s main landmark.

At the end of January 1864, the prison was completed. It began accepting its first trainloads of prisoners the following month. In charge of the camp was a confusing array of officers who held varying levels of authority.

Still, inside the stockade, the Confederate officer who held control was the infamous Captain Henry Wirtz.

The Guards

Contrary to popular belief, there were not just old men and young boys guarding the prisoners.

The first initial camp guards included survivors of several decimated Confederate regiments, including the remnants of the disgraced 55th Georgia infantry who had been wiped out and surrendered en masse during the battle of the Cumberland Gap.

Augmenting these soldiers were several regiments of Georgia reservists. These men had an average age of late twenties to mid-thirties.

Many of them were family men and farmers; these soldiers were considered older and less suitable for frontline service. Their arms matched accordingly.

Most of the weapons provisioned by the camp came from the Macon arsenal. A majority of these weapons were antiques even for the time, some dating back to the Revolutionary War.

Augmenting these personal weapons were teams of dogs that scoured the perimeter day and night, looking for escaped inmates.

Though lacking in proper arms, the most fearsome weapon the 3,000 or so guards had against the prisoners was a battery of Florida light artillery.

These four light cannons stood prominently along the 15-foot-high walls of the palisades. In their guard towers, nicknamed pigeon roosts, the guards watched the prisoners twenty-four hours a day.

Inside the stockade, Captain Wirtz had a wooden line called the deadline, installed around April 1864.

The purpose of the deadline was that any prisoner who crossed it was supposed to be shot on sight. However, available records show this was not the case. Only about 11 men were killed by Confederate sentries.

However, the guards liked to show force by performing frequent parades to show off their numbers or occasionally firing the cannon into the middle of the creek to prove they worked.

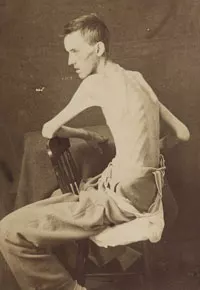

Despite these shows of bravado, the fact remains that though there were about 3,000 guards on paper, only about 1,200 or so were ever fit for duty or present at one time.

Of these, only about 300 ever stood watch, actively guarding the prisoners at any given time. This meant that at the prison’s peak, there were 100 prisoners to every guard standing watch at that time.

But why didn’t the prisoners choose to escape in a giant rush?

Life At The Camp

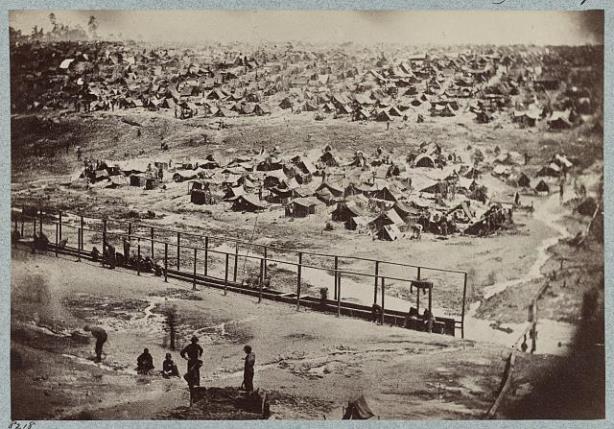

One of the main reasons why prisoners never attempted a mass escape was because of the physical condition of many. The food of the place was horrible.

Though initially told to procure beef locally, the cattle in the area were so few and so low quality from three years of war that Captain Wirtz had to have salt pork trained in from far-flung supply depots across Georgia.

But even with trying to reach out to supply depots, meat was still a rare treat in prisoners’ diets. Most often, the prisoners were fed beans, rice, and corn meal. However, even these meager rations proved useless due to several factors.

Firstly, the kitchen meant to serve the inmates was woefully inadequate.

Designed to hold no more than 9,000 prisoners, with a population above 30,000 by that summer, the kitchen did not have the capacity, or frequently the firewood, to cook all the meals. Often, guards distributed raw, uncooked rations, and prisoners had to cook them themselves.

Because of this, the huge number of fires for both cooking and warmth coated the prisoners in a constant layer of soot.

The lack of suitable lumber in the area for cooking and heating meant nothing to use for shelter. Hopefully, a man had been captured with his tent or extra clothing that could be used to provision a makeshift shelter.

Otherwise, men would freeze at night, be wet in the rain, or bake in the southern summer.

Due to the lack of high-quality food, proper shelter, and bathing facilities, the vast majority of prisoners were weak, covered in vermin-like lice and fleas, and made with hunger. There were a few ways to alleviate their position.

One of these ways was to participate in one of several prisoner jobs the Confederates needed. Prisoner labor comprised the bulk of the wood-cutting parties, hospital attendants, bakery workers, and gravediggers.

Men who served on work parties received double rations and the opportunity to forage and trade for food.

The next way men could survive was by trading for food, clothing, money, and valuables. A whole prison economy flourished, fueled by a steady influx of new inmates, corrupt guards, and a willing civilian population near the camp.

Despite the plight of many, some men made a fortune in the camp, including one man who came in with nothing more than a button and left with 3,000 dollars in his pocket.

Most commonly, new arrivals would trade clothes for food from guards. This is why the deadline was largely unobserved since if a prisoner was not on a work detail, he could exchange goods with guards in their pigeon roosts.

But even with this booming prison economy, very few got wealthy. Most men would not have survived without the kindness of sympathetic prisoners, guards, or civilians who ministered to the inmates.

However, this help was not enough to prevent the dying of up to 100 men a day at the worst times of the camp’s existence.

In the beginning, the first 300 men who died got their own coffins. The following 900 were laid on top of boards. The next 12,000 got enough space for their emaciated bodies in a mass grave.

Ironically, the wagon and cart bringing the daily rations would be the same cart to haul away the dead after each muster that occurred twice a day.

With such horrific conditions, it would be inconceivable for some men not to want to escape. And indeed, several hundred did.

Escapes

Many rumors still exist today about men tunneling their way to freedom. However, the historical record does not support any of them. But that did not stop many men from trying.

During Captain Wirtz’s tenure, he estimated at least 83 tunnels were dug underneath the grounds of Andersonville. Some of these tunnels were quite complex, with them extending for hundreds of feet and up to eight feet beneath the surface.

Digging the tunnels was a great pastime for men who had nothing else to do, and it gave them hope in a hopeless place.

But digging a tunnel was a huge undertaking. Not only did prisoners have to dig far enough under the palisades, but they also had to keep the hidden dirt away. Guards frequently tried to observe digging activities but also discovered tunnels in other ways.

For example, sometimes, a tunnel made it under the palisade, and the logs would sink into them. Guards frequently assisted in freeing prisoners stuck this way.

Other ways included using slaves to prod the perimeter with steel bars to see if they sunk into any hidden mineshafts. However, the most frequent way guards found out about tunnels was through tunnel traitors.

These prisoners, seeking gain for themselves, such as food, would relay tunnel construction plans to the Confederates. These men were among the most despised in the camp.

Because of them and the difficulties in building tunnels, the most frequent escapes came from leaving working parties.

The vast majority of escapes happened during the lumber-cutting parties, where men were already in the woods and isolated away from the camp.

Others chose to run away from the kitchen or in the hospital where they worked as attendants. Others still came up with more ingenious ideas.

Some secreted themselves away as corpses on the death cart. This was not hard to do when over 100 men were dying a day.

But after Captain Wirtz had surgeons inspect the bodies of the deceased after a few men escaped this way, several soldiers came up with an even more incredulous idea.

Among the prisoners were representatives from several former Confederate soldiers who had enlisted in Northern service only to be captured again.

Several soldiers took parts of their greyish uniforms and fastened new uniforms out of them. During roll call one day, the two pretended to be guards, leaving with them and right out of the front gate.

Of all the escaped prisoners, only about 32 were recorded to have made it back to Union lines. About half were recaptured and returned back to Andersonville.

Of the remaining balance, several are known to have been recaptured and returned to other rebel prisons. The remainder either died or returned to civilian life with notifying the army.

Another thing that prisoners did not notify the army about was the fact that many changed their identities in prison. Due to the prevalence of bounty jumping, a fear of not letting their families know they died at Andersonville, or simply taking a dead man’s rations, it was common for soldiers to assume fake or multiple identities.

Because of this, several thousand soldiers are believed to have done this, and it was so common that in several cases, one soldier was able to claim multiple pensions.

At the same time, another returned to Andersonville years later, only to see he had a gravestone there.

Another aspect of the camp that remains shrouded in mystery is the story of one of the camp’s most infamous moments: the hanging of the Raiders.

Raiders vs Regulators

As discussed previously, there was a booming prison economy inside Andersonville.

Especially after the influx of a huge crop of prisoners in April 1864 that brought in about a million dollars worth of money and property, there were plenty of opportunities for theft and misdeeds.

Among the prison population was a small group of inmates that preyed on new arrivals and the weak. Calling themselves the Raiders, this loose group of men used violence to beat, rob, and intimidate prisoners to hand over money, food, clothing, and other valuables.

To protect themselves against the Raiders, the prisoners formed 13 companies of 30 men, each of whom called themselves the Regulators.

These men would stick up for weaker prisoners and ensure that justice was meted out if they ever caught a Raider. However, over the coming months, the Raiders began to become more bold until, at the end of June 1864, a Raider stabbed a sergeant to death during a robbery.

After that incident, Captain Wirtz withheld the food ration for two days until the prisoners could produce a list of Raider names.

After identifying a list of 84 Raiders, the prisoners had the guards arrest them and hand them back over to the prisoners to do as they saw fit. The prisoners created a court that dispensed justice to the captured men.

The majority of the men were sentenced to run the gauntlet of prisoners where they would be beaten with clubs. If they survived, they would then work on a chain gang. Three Raiders supposedly died during the beatings.

The remaining six, considered the worst among them, were sentenced to hang.

Captain Wirtz approved of all the proceedings. Though prisoners smuggled in the boards used to make the gallows, he sent in slaves to construct them. Once built, the prisoners hanged the six Raiders.

Their graves remain to this day separate from the other prisoners who died at Andersonville.

Conclusion

By the end of August 1864, it was decided to transfer the majority of the prisoners to Andersonville.

The main reason for this was that Sherman began his march through Georgia, and it was widely believed he would seek to liberate the camp; however, though he had tried to do so in July, his cavalry raid failed to make it past Macon, Georgia, much less down to Sumter County.

Instead, he was focused on Savannah and then the Carolinas, but the Confederates did not know that. After moving the bulk of the prisoners to a new camp in Millen, Georgia, and several other places, about 8,000 of the sickest prisoners remained.

The number of prisoners would continue to dwindle through death and transfer until the end of the war, when only a few thousand remained.

Once the war had ended, Captain Wirtz became the poster child for what had transpired there. Though he was the day-to-day middleman and reported to several higher-ranking officers, he was held accountable for those who died.

After being tried by a military tribunal, he was hanged on November 10, 1865. The land was eventually bought by the Union veteran organization, the Grand Army of the Republic, and then turned over to the federal government.

Today, Andersonville serves not only as a testament to the tens of thousands held prisoner there but as a memorial to all Americans held captive in all American conflicts.

Sources

https://archive.org/details/cu31924095623504/page/4/mode/2up?view=theater

Leave a comment