Mount Aconcagua is the highest mountain in the Western Hemisphere and isn’t taken lightly by mountaineers. All too often, the unpredictability and harshness of the conditions have caused mountaineers to turn back before reaching the 22,000-foot summit.

Some adventurers have never made it back from their expedition.

In this case, teacher Janet Johnson and NASA engineer John Cooper would attempt to climb the mountain nestled on the Argentine border. As experienced mountaineers, nobody expected them to succumb to the famous Polish Glacier.

The circumstance surrounding their deaths and what happened in the aftermath is shrouded with mystery.

The Mountaineers

The summit of Mount Aconcagua was first reached in 1897 by Swiss man Matthias Zurbriggen. Then, in 1934, a group of Polish explorers successfully tackled a more dangerous route of the mountain, which saw them pass a vertical 200-foot glacier. This would then be named the Polish Glacier.

By 1973, there had been 25 deaths on the mountain. This highlighted the fact that this was by no means a beginner’s expedition, especially in years gone by: there was no high-tech equipment or GPS trackers for climbers to utilize.

They simply had the tools on them and their wits. A flare gun was the best they had to signal a distress call.

Carmie Dafoe was head of a climbing club based in Oregon. He organized an expedition to climb Mount Aconcagua and assembled a team to ensure the trip went smoothly. Miguel Alfonso, an Argentina native and veteran climber, would serve as the guide.

The party members were psychiatrist Jim Petroske, physician Bill Eubank, farmer Arnold McMillen, police officer Bill Zeller, and student John Shelton. Later on, NASA engineer John Cooper joined the team.

Shortly before the expedition, Carmie announced the final member of the crew: a woman in her 30s named Janet Johnson.

Any mumblings about a woman joining the crew were quickly quashed when her expertise and skillset were revealed.

She was one of the first 20 women to become a “fourteener,” which is a person who has reached every summit of Colorado’s peaks over 14,000 feet. There are more than 50 of these peaks.

Her day job involved working with children, but she’d recently taken a year off to travel. She was finishing that off by climbing Aconcagua.

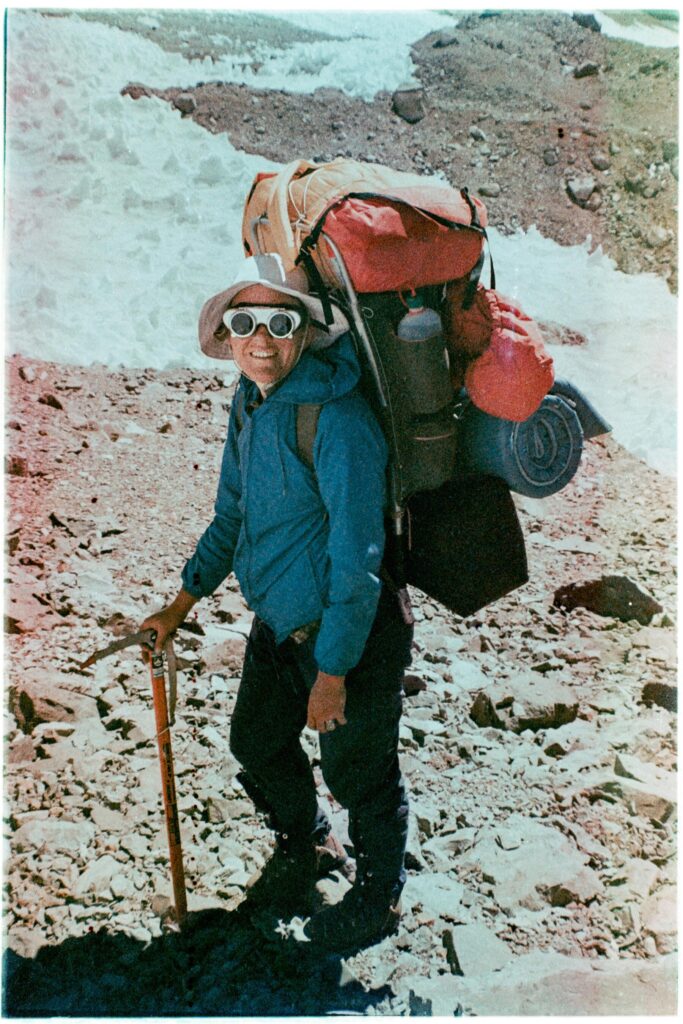

As usual, she filled her backpack with essentials, labeled everything with her initials, and added her address to more expensive items, like her Nikkormat. The camera, called Nikomat in Japan, was a more affordable option for those wanting to take professional-style pictures.

Janet and the nine other members of the climbing party set off on January 19, 1973. When they arrived in Argentina, news crews were eager to meet the mountaineers and get their story before their ascent of Aconcagua.

One of the Argentinian journalists found that the American adventurers didn’t seem like the usual crew who would traverse the mountain. They didn’t seem overly prepared for their expedition, nor did they seem as tight-knit as you’d expect from a climbing party.

Each person’s picture was taken before the group set off. Only eight of those individuals would return.

Climbing Mount Aconcagua

The adventure was a mess from the start.

Bill Eubank got sick before reaching base camp. Once there, the group was met by Roberto Bustos, who was employed to manage the camp.

Much like the Argentinian news reporter, he sensed the group wasn’t cut out for the expedition. He noted the shiny, new, expensive gear they all had but also felt like the group had an “each man for himself” mentality.

Carmie Dafoe set out the group’s hierarchy. He’d be the leader. Jim Petroske was the deputy. Despite his sickness, Bill Eubank was placed third in line.

Reaching the peak would take at least a week. Even with the hierarchy put in place, the group quickly fractured. Carmie and a few other climbers stayed at Camp One while the rest headed to Camp Two.

They managed to make their way to the base of the Polish Glacier and set up the third camp. By this point, the group was at over 19,000 feet. Thankfully, they got there just before a storm swept the mountain.

The next day, the group set off up the glacier, though Jim Petroske was suddenly hit with altitude sickness part way through the journey. The guide, Miguel Alfonso, escorted Jim back to camp so he could regain his coordination.

This meant the group was well and truly fractured and missing their experienced guide. Left alone were Janet, John, Bill, and Arnold.

Despite the wealth of experience between them, particularly from Janet, none of the group had ever been this high before. They struggled up the glacier and didn’t reach their goal of hitting the summit.

They got to 21,000 feet before calling it a day. The altitude and weather conditions had proved difficult for them.

So, they decided to set up a makeshift camp. Using their sharp ice axs, they made a shallow shelter on the glacier. They laid out space blankets on the floor and set up for the night. They didn’t have the luxury of tents or sleeping bags. They just had to make it through the night.

By morning, John Cooper was half covered in snow. The harsh wind had blown the snowdrift toward them, and he had to be dug out from beneath the dusting. John decided he didn’t have it in him to try and tackle the summit—he was heading back. He was frozen and exhausted.

As he tried to make his way back to camp, John died on the summit. Janet would meet the same fate shortly after.

The details of what happened and why each explorer died have remained a mystery for decades.

The Aftermath Of The Deaths

Bill Zeller and Arnold McMillen were the last people to see Janet and John alive. Once they made their way back to camp, minus two members of the group, the authorities were called.

Each man gave a thorough version of events to the police, though neither man’s story would match the others exactly.

The reason for this was put down to the effects of enduring such a stressful, high-altitude environment.

All of the American mountaineers, plus the guide Miguel Alfonso, were brought in for questioning.

Still, the police hadn’t retrieved the bodies, so there was little they could pin on any of the men. They needed to find the bodies before they could begin accusing anyone of murder.

Later that year, Miguel spearheaded a four-man team that went looking for the missing mountaineers.

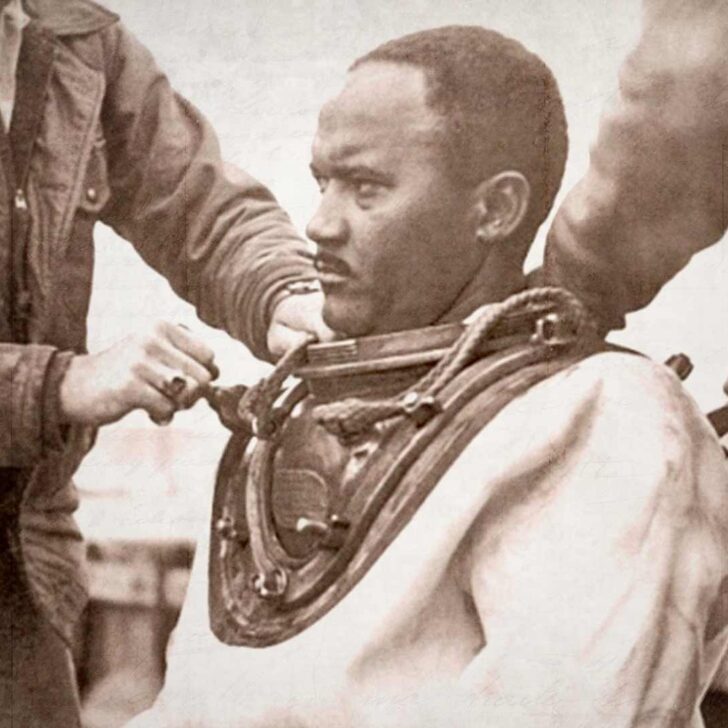

As expected, when the group reached the Polish Glacier, they found some of the missing explorer’s items. Just ahead of them lay John Cooper’s corpse.

The state in which they found him was unusual. He was only wearing one crampon, a traction device for his feet. He didn’t appear to have his ice ax, a must-have item when traversing the mountains.

The area of the slope he’d been found on wasn’t a particularly steep one. He had a bloody wound on his stomach. His face was frozen in an expression of horror.

John’s body was brought back for an autopsy. We still don’t know the full findings of the postmortem; these were sealed from the public. We do know that John had suffered injuries to his brain, which has been listed as his cause of death.

An inquest into whether this was accidental or murder culminated in more questions. The most prominent question was: Where’s Janet Johnson’s body?

What Happened To Janet Johnson?

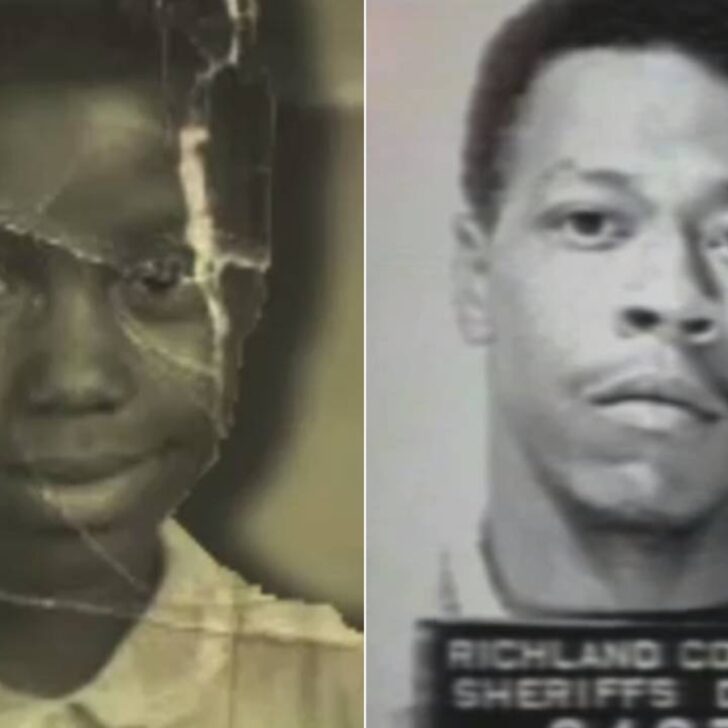

In 1975, three climbers found Janet’s body. Alberto Colombero, 17, his father, Ernesto, and family friend Guillermo stumbled upon her corpse.

Alberto was too young to notice anything more sinister than a woman who’d succumbed to the harsh weather of the mountain. Ernesto and Guillermo were experienced enough to know better.

Janet was laid face up. Her bone stuck out of her face; the skin had degloved after two years of exposure. Again, she was only wearing one crampon. Her ropes were wrapped around her. Just like John, she’d also been found without her ice ax. Atop her body was a rock.

Despite finding Janet, the mystery of her and John’s deaths remained unexplained. In fact, there were more questions now than there’d been before.

The case was cold and steadily forgotten about until, in 2020, two climbers encountered something interesting while climbing Mount Aconcagua: an old camera perfectly preserved by the freezing temperatures.

Taking a closer look at the almost 50-year-old camera, the mountaineers saw the holster had a name embossed: a woman’s name, Janet Johnson, followed by her Colorado address.

The lens had been broken, but other than that, little damage had been done to the device. The pair took the camera back to camp and announced they’d found something interesting.

Unbeknown to them, it held Janet’s final moments before she met her untimely death on Mount Aconcagua.

In total, Janet took 24 pictures. She’d taken photos of her fellow climbers and snapped the white serenity that surrounded them.

The pictures help piece together a timeline of her death. It appeared she’d taken more pictures after John Cooper had decided to make his way back to camp. Her final photo is a late afternoon snap of the Andes.

What happened after this picture is still unknown.

In a case this cold, the photos offer more mystery and intrigue to a case that is begging to be solved. There are many questions left unanswered in this suspicious double death, though the case is unlikely to be solved with the current evidence available.

As the camera’s discovery proves, Mount Aconcagua can preserve evidence for decades; perhaps another mountaineer will eventually stumble upon something that finally solves this case.

Leave a comment