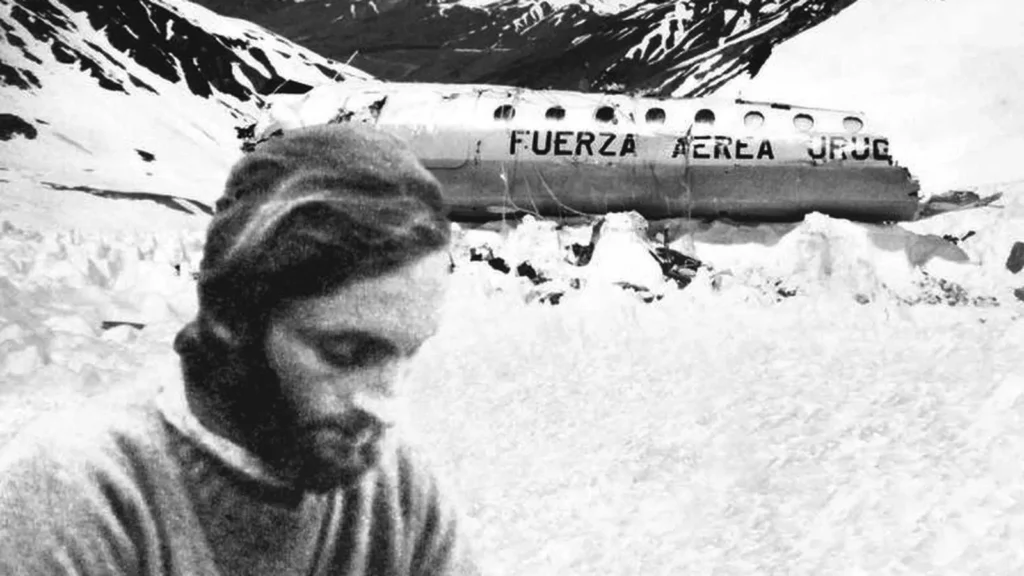

The events of Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571, often referred to as “The Miracle of the Andes,” has everything you need to write a movie script: a dramatic plane crash, a tragic loss of life, and a survival story against the odds.

Throw in some horror elements, and you’d think the tale of Flight 571 is a work of fiction–but it’s not. It all really happened.

On October 13, 1972, the passenger aircraft Fairchild FH-227D was chartered by the Uruguayan amateur rugby team Old Christians Club to take them to Chile for a match.

The twin-engined aircraft carried 40 passengers and five crew members, with less than half surviving the tragic crash.

Those who didn’t make it were eaten by the survivors in order to stay alive in the harsh conditions of the Andes mountains.

But why did the plane crash, and how did 16 people survive the tragedy?

The Departure Of Flight 571

The story starts on October 12, 1972. The Old Christians Club rugby team was in high spirits when they boarded Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571, excited to embark on the journey from Montevideo, Uruguay, to Santiago, Chile.

Aboard the plane were the rugby players, their friends and family, and the five crew members. Chartering the aircraft was expensive, so the rugby players invited loved ones to join them on the journey and help split the costs.

The excitement soon waned when poor weather over the Andes mountains meant the flight had to land in Mendoza, Argentina until the storm passed.

The group stayed here overnight and departed again just after 2 pm the following afternoon when the weather was deemed safe enough to travel through.

The Fairchild aircraft was built to reach 28,000 feet maximum, meaning flying through the Andes mountains would be dangerous.

The pilot would have to be precise and careful to avoid crashing the plane if they chose this route to the destination. Instead, the pilot and co-pilot—Colonel Julio César Ferrada and Lieutenant-Colonel Dante Héctor Lagurara, respectively—plotted an alternate route.

They planned a U-shaped route that took them across the Planchón Pass volcano. Although it added a little more time to the journey than usual, it was designed to ensure everyone got to the destination safely.

Sadly, this plan would be in vain.

Around an hour after setting off, the pilot notified air control that he was making his way over the pass and would soon reach Curicó, Chile.

After passing the Andes into Chile, the plane was due to head north and begin the descent into Pudahuel Airport in Santiago. This is when things went downhill.

The Disaster Begins

Pilot Julio Ferradas was experienced. He’d flown across the Andes almost 30 times before. The colonel was training co-pilot Dante Lagurara, who was handed control of the plane for most, if not all, of the journey.

The quality of the plane—or the lack thereof—was a running joke between the pilots. While the plane was just four years old, the airmen knew it was underpowered and referred to it as the “lead sled.”

While this may have been true, it wasn’t the lack of power that caused the plane to crash; it was pilot error.

Inexperienced co-pilot Lagurara had misjudged the plane’s location, believing it to be almost at their destination in Chile. In reality, the plane was still in the Andes.

It’s believed the co-pilot made this mistake due to cloud cover, which made it difficult to judge his location accurately. Plus, he radioed in to Pudahuel Airport in Chile to request permission to descend.

The air traffic controller agreed, not realizing that the plane was nowhere near Pudahuel; instead, it was surrounded by the mountains.

The plane quickly descended, and once through the clouds, the passengers aboard could see they were close to the mountains.

They were unaware this was out of the norm, and even when severe turbulence hit, the rugby team joked about it, not realizing the severity of the situation.

The pilots, however, did realize the severity of the situation by that point. They tried ascending, taking the plane to an almost vertical position to get out of the certain crash scenario.

Maximum power was applied to the aircraft to gain altitude, which allowed the plane to get its nose over the ridge, but the tail of the plane clipped the mountain. Then, the right wing struck the peak.

In the ensuing strikes, the tail end of the plane was lost, which in turn caused three passengers and two members of the crew to fall out of the enormous hole.

The plane was still hurtling forward, though the left wing was soon ripped off. The pilots no longer had control of the aircraft, and two more passengers succumbed to the hole in the tail of the plane.

Eventually, what was left of the aircraft and its passengers crashed into a snow-filled peak and hurtled over 2,300 feet down the slope.

The snow bank below caused the aircraft to stop suddenly, which had been blasting down the mountain at over 200 mph. The impact hit the cockpit first, killing pilot Ferrada instantly.

The impact had caused the passenger seats to break free, and people were shot through the air, still strapped in.

The Chilean control tower had been trying to contact the pilots to no avail when the expected landing didn’t happen. A search team was sent to find the plane near the Chilean border. However, they weren’t there; they were in the Andes.

Surviving In The Mountains

The crash killed 12 of the 45 people on the plane. Thirty-three people survived the initial impact.

Hurt, dazed, and terrified, the survivors made it out of the wreckage and did their best to assess the situation. They were surrounded by snow, had no respite from the freezing temperature, and had little around them in the way of resources.

They had what remained of the fuselage to provide some small level of shelter from the weather, but that was it.

The badly injured survivors found what food they could that remained on the plane. Cheese, wine, and chocolate made up most of what was available.

It helped fuel them to make a more comfortable shelter in the fuselage, build a solar-powered water collector using metal found from the wreckage, and makeshift snowshoes out of cushions.

As the days passed, surviving passengers were slowly realizing some of their loved ones had passed in the accident. Rugby player Nando Parrado lost his mother and sister in the crash. His mother died on impact, and his sister died days later.

The food supply was quickly depleted. Within less than a week, there was nothing left for the group to eat. To fill their stomachs, some of the group took to eating the stuffing from the plane seats, which quickly made them sick.

A further search of the wreckage saw the group find an AM transistor radio. They used electrical wire foraged from the debris and used this to keep updated with the news reports of the missing plane.

The white plane blended in with the snow, meaning rescue teams had flown over the wreck and missed it. To combat this, survivors positioned luggage to spell “SOS,” though this proved futile.

On day 11, via the radio, the group learned the search for them had been called off.

As a result of the resources drying up and perhaps feeling hopeless due to nobody looking for them, more members of the group began dying, unable to survive the freezing temperatures and lack of food.

Six passengers passed in quick succession, then 16 days after the crash, on October 29, another tragedy hit.

A huge, unexpected avalanche hurtled down on the crash site, filling what remained of the fuselage with snow. Eight more passengers perished because of this.

The survivors knew their days were numbered. Understanding that rescue teams had been called off and that there was nowhere to obtain food, the group agreed: whoever died permitted the others to eat their body once they’d passed.

It was not a decision they came to lightly. They prayed before the agreement, unsure if they could consume their friends, family, and classmates. However, it would be the only option they had to stay alive.

When the time came, the first body consumed, which had been preserved in the freezing snow, was cut into “meat” by a shard of windshield glass.

Medical student Roberto Canessa could sense apprehension in the group and consumed the first bite as an example. Some others followed.

With the little sustenance provided by the flesh, some group members decided to wander further away from the wreck to find a possible escape route.

Roberto Canessa, Nando Parrado, and Antonio Vizintín, the most physically fit of the group, set out to look for help. Antonio had to return to the wreckage due to ill health. Roberto and Nando continued their mission, heading east in the hopes that it would take them to Chile.

The trek was arduous, exhausting, and difficult. Still, the men kept on and eventually encountered some herdsmen across a river from them. They shouted over, but due to the noise of the water, they couldn’t hear one another.

Instead, they communicated by wrapping paper around rocks and throwing the message across. The herdsmen told the survivors they’d come back the next day with help. So, hopeful, Roberto and Nando sat by the river all night, awaiting help.

As promised, the herdsmen came back the next day and brought help. They notified authorities, and the survivors were saved. Helicopters were sent to collect the individuals still trapped beside the wreckage.

Naturally, the media was intrigued by the unbelievable story, although eventually, they focused on one aspect of it: Consuming human flesh.

The media had it wrong, however, stating that the survivors had killed others in order to stay alive and pointed to photos taken by the Relief Corps showing a half-eaten leg found at the crash site.

The survivors had no choice but to admit the acts but stressed they got permission to do so prior to each person’s death.

The crash site is now a popular tourist site, attracting hundreds of yearly visitors. The tourists can pay their respects to those who lost their lives in the Andes.

Those who didn’t survive the tragedy were buried in a 400 by 800-meter grave. There is also a monument at the site to memorialize all Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 passengers.

Sources

https://www.britannica.com/event/Uruguayan-Air-Force-flight-571

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/premium/article/flight-571-andes-crash-true-story

Leave a comment