The ocean is the source of many mysteries. But there is one mystery that is better known than any other: the baffling case of the Mary Celeste.

The crew and passengers of this ship vanished completely in 1872.

The ship was found drifting and abandoned in the Atlantic Ocean, but in good condition. All that was missing was one of the ship’s boats. And the ten people who had set sail in the ship one month earlier.

The mystery of what happened to the people on board produced some sensational and unlikely theories in the contemporary press.

Until the present day, people continue to speculate about what may have happened. But even now, we can’t be sure…

Let’s take a look at one of the most enduring of all maritime mysteries.

The Amazon

The ship that would later be renamed as the Mary Celeste was built at Spencer’s Island, Nova Scotia. She was launched in May 1861 and named the Amazon.

She was a brigantine, a two-masted sailing ship, almost one hundred feet long.

The Amazon could carry up to 200 tons of cargo in her holds. Accommodation for her captain and crew was Spartan, with simple cabins on deck. From the beginning, she wasn’t considered a lucky ship.

On her maiden voyage, a few weeks after she was launched, her captain, Robert McLellan, died. He contracted pneumonia within days of setting foot on the new ship, and she returned to Nova Scotia.

With a new captain, the ship sailed for the port of Dover with a cargo of timber.

In the Strait of Dover, she accidentally rammed another cargo vessel, which immediately sank. In 1867, the Amazon ran aground during a storm near Cape Breton. The crew escaped, but the ship was abandoned.

The grounded vessel was salvaged, repaired, and sold at a public auction in 1868.

Its new owner, Richard W. Haines, had further repairs done and the ship undertook cargo runs for around one year. Haines also gave the ship a new name: the Mary Celeste.

The Mary Celeste

Despite the change of name, the ship seemed to continue to attract bad luck. Haines owned the ship for one year before he was forced to sell it at auction to pay his debts.

The ship was purchased by a group that included a very experienced seafarer, Captain Benjamin Spooner Briggs.

Under new ownership and commanded by Captain Briggs, the Mary Celeste undertook several successful voyages from North America to Europe.

However, Briggs didn’t enjoy being parted from his wife Sarah and his daughter Sophia Matilda, born in 1870.

Voyages could take up to four months, and in 1872, Briggs decided that his wife and daughter would accompany him.

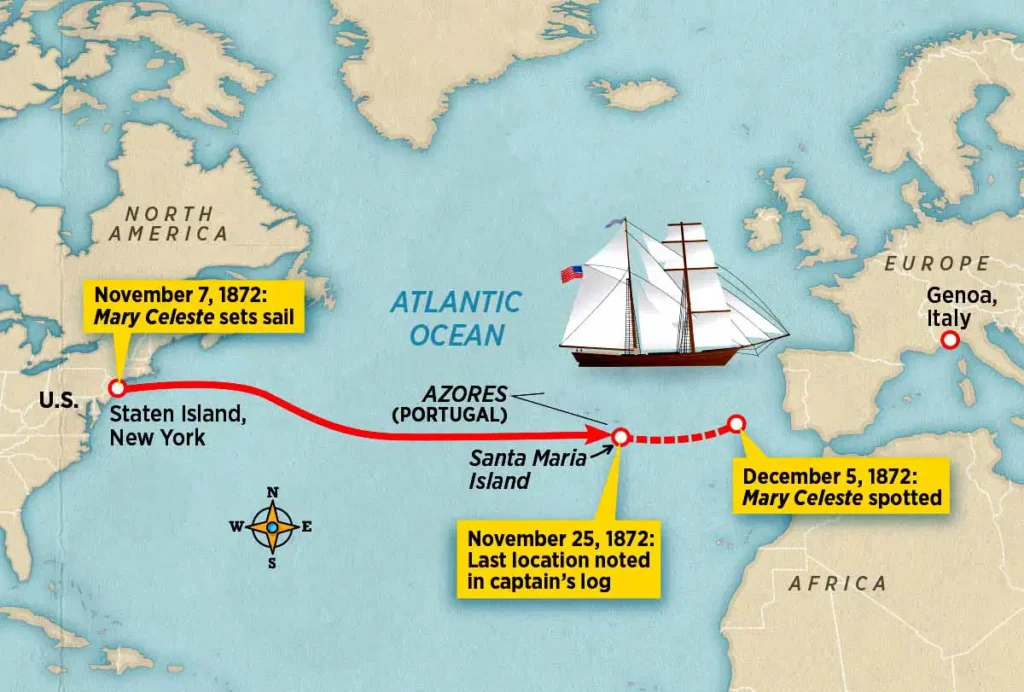

In the fall of 1872, Briggs took the Mary Celeste to New York. She was contracted to take 1,700 barrels of alcohol from New York to Genoa, Italy. We don’t know precisely what kind of alcohol was involved, but it was likely industrial ethanol or methanol.

Alcohol of any kind was a potentially dangerous cargo because of its flammability. Briggs had never commanded a ship carrying such a cargo before. He carefully supervised the loading of the Mary Celeste’s holds.

Sarah and Sophie joined Captain Briggs in New York in late October. Both would share the cramped Captain’s cabin on the main deck. Also on board was the first mate, Albert G. Richardson, and the second mate, Andrew Gilling.

The cook was Edward Head and the four other crew members were German seafarers. All were experienced and when Mary Celeste left New York on November 5th 1872, no-one expected problems.

Then, the weather changed…

A storm forced the Mary Celeste to anchor off Staten Island, where it remained for two days. On November 7th, the weather improved and a pilot guided the ship through the sandbars that surrounded the harbor. The pilot left the ship and returned to New York on a small boat.

The Pilot would be the last human to see the people on the Mary Celeste…

Discovery

One month later, on December 4th, 1872, another Brigantine cargo ship, the Del Gratia, was also crossing the Atlantic. The British Del Gratia was bound for Gibraltar and was carrying a cargo of flammable petroleum.

After enduring a storm that had lasted several days, the ship had finally entered calmer weather.

Approximately halfway between the Azores and the coast of Portugal, the lookout on the Del Gratia spotted another ship. The Captain, David Morehouse, noted that the other ship was showing few sails.

That was unusual, and Morehouse ordered the Del Gratia to approach.

No-one responded to calls and the ship, which was quickly identified as the Mary Celeste, appeared to be abandoned. Three men used a small boat to transfer to the drifting vessel. They boarded her, and found no sign of her crew or passengers.

On one of the masts, a tattered sail fluttered. A check showed around three feet of water in the bilges. More than ideal, but the ship did not seem to be taking on water and was in no danger of sinking.

A search revealed the belongings of Captain Briggs and his family and those of the crew. But there was no-one on board. The last entry in the Log Book was dated November 25th and it gave no indication of trouble.

Everything suggested that the occupants had left in a hurry – the crew’s wet weather gear was still aboard. But there was no obvious reason that the ship should have been abandoned. And the cargo of alcohol appeared to be intact.

Captain Morehouse hatched a bold plan. A skeleton crew of just three men would be put aboard the Mary Celeste. They would sail the ship, alongside the Del Gratia, to Gibraltar.

The maritime law of salvage meant that the ship and its cargo would belong to its salvors. And the cargo on the Mary Celeste was valuable, worth up to $40,000. This was far more than the value of either ship.

On Friday 13th November, the Mary Celeste and the Del Gratia arrived safely in Gibraltar. The Mary Celeste had been saved, but the mystery of her missing crew and passengers was only beginning.

The Mystery

When British authorities examined the Mary Celeste in Gibraltar, they could find no evidence of foul play. But nor could they find any explanation for what happened to those on board.

It appeared that the ship’s boat was missing, but that didn’t explain why the ship had been abandoned.

The ship itself had clearly passed through heavy weather, but none of the damage it had received made it unseaworthy. A series of inquiries followed, but none were able to suggest what might have happened. Speculation was rife, but proof was lacking.

The mystery remained but fell from public attention until 1884, when a young writer published a short story. Arthur Conan Doyle was then relatively unknown, though he would later become world-famous as the creator of Sherlock Holmes.

In 1884 Cornhill Magazine carried one of his early short stories, J. Habakuk Jephson’s Statement.

This was a fictional piece purporting to be written by a survivor of the “Marie Celeste.” It told of how the crew mutinied, killing the captain, and the ship was then taken over by African warriors.

There is no evidence that Conan Doyle intended this as anything other than fiction. However, many elements of this short story found their way into the annals of this mystery.

Accounts of unfinished meals, a bloody sword, and a steaming cup of tea frequently appear in the story. None happened in real life, though many supposed genuine accounts of this story include these things.

Fiction and truth have become so intertwined that it is now difficult to find unembellished accounts of this story. Even the name that Coman Doyle gave to the ship in the story, “Marie Celeste,” is often mistakenly cited.

Is it possible to ignore the fiction and solve the mystery of the Mary Celeste?

What Really Happened?

Some fairly extreme solutions for this mystery have been proposed. It has been suggested that a tornado or even an underwater earthquake might have caused the abandonment of the ship.

Or that a fire or explosion may have caused the crew to fear for the safety of the cargo. It has even been bizarrely suggested that a giant squid might have attacked the ship.

However, there was no evidence of any serious damage to the ship when it was examined in Gibraltar. The Mary Celeste was still seaworthy, as evidenced by her successful voyage to Gibraltar.

But something caused Captain Briggs, his family, and the crew to leave the Mary Celeste in the Mid-Atlantic. In heavy weather, that was very risky, so some compelling threat must have been involved.

An objective analysis of the evidence suggests that this may have been the fear of an explosion.

The fumes from the cargo of industrial alcohol would certainly have been flammable. These may have built up in the hold – one of the hatch covers was found to have been removed. Perhaps this was an attempt to vent fumes from the hold?

Did Captain Briggs, inexperienced in the carriage of alcohol, fear an explosion? Did he order his wife, child, and the crew into the ship’s boat? Was this attached to the Mary Celeste by a tow rope?

Briggs may have hoped that this would allow fumes in the hold to dissipate safely. Instead, as the weather grew worse, the tow rope may have parted. Adrift in a heavy sea, the small boat would not have lasted long.

It isn’t as dramatic as an attack by a giant squid, but it seems possible that this is the solution. But the truth is that we may never know just what really happened in late November 1872.

Perhaps that’s why this mystery remains the topic of debate and discussion 150 years later.

Sources

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/abandoned-ship-the-mary-celeste-174488104

https://www.history.com/news/what-happened-to-the-mary-celeste

Leave a comment